Born in 1950 in Santa Monica, California, Bill Reynolds is a man who has reinvented himself many times, but through all of his endeavors there runs a creative spirit, a sense of authenticity, and a profound appreciation for the iconic cowboy culture and heritage of the American West. In this free-ranging interview, Bill espoused his thoughts on creativity, cattle ranching, and the concept of California...among other things. Our conversation took place on September 16, 2015 in his Solvang home office, with Cynthia and Rebecca as interviewers.

"Communicating like we’re doing here and giving of your time to be a part of something that’s larger than you...at my age, I just figure that’s the important stuff. It’s hard for me to be around people who don’t get this."

Hope, A Set of Values, and A Handshake

CW: How did you come to be here?

BR: When I was very young, my family would come to the Alisal Ranch, and it would be one of those family treks, every Easter as far back as I can remember. We’d take four or five of those cabins there…and it was a pretty mystical place. But I only saw it once a year, in April, which is a pretty nice time to see it.

My wife Kristin and I came up here on our first date, forty years ago in May. We were married about six months later, and it was always our intent to come back here someday. We had horses…and we lived in Malibu…and Malibu, it’s sort of like Jackson Hole, it’s not really a place, people come and they leave. It was getting so anti-horse that we really couldn’t stay anymore, and we had young kids and we were very attracted to the Ballard School District, which was wonderful. And so we moved here in 2000, fifteen years ago. It was something that we had consciously thought about for twenty-five years, simply because it was one of those places…when you come over 154, right at the top and you see that first view, the way you see the mountains right through, that’s like coming home.

So we were able to do it. I sold a business, and got into publishing. The worldwide inter-web was helping me; that was the reason we were able to do it. I figured all right, it’s a big crapshoot, and I’m not really a crapshooter, but we thought, "This could be a real opportunity, let’s see if it works. We’re young enough. If we have to reinvent ourselves, we can still do that."

CW: Can you talk more about what called to you about this particular place, this part of the world? I am always amazed that I get to be here.

BR: You get to be in a very special place. You know, as an aside, in 1969 I was working as a page at CBS in Hollywood and we always got all the trade papers and there was a lot of down time, and in Variety, there was this ad for the Hollister Ranch. $100,000 for a hundred acres. I had been up there. We’d snuck in, surfing, both through Jalama and on a boat. So we had a bunch of guys, we were all trying to put ten grand together, never could. So there was this moment where I saw that. It was one of those aha moments. Permission.

I guess the thing about this place is that even though it is evolving and growing and changing dramatically from when we first got here from a horse and cattle culture to a vintner culture–which is bothersome to me, but everything evolves, you sort of have to go with it–but even with that, it has still remained pretty much conceptually the same. The people are pretty much the same. Most everybody is here for pretty much the same reason. It’s just a place of great history, with all these land grant ranches around here, and how that evolved and how, like the San Julian is even the same family, and so there’s a respect, not just for the land, but what it represents. Even though 101 cuts right through it.

So I’ve looked at it as, where would I want to go? Where else would I go where I’d have this? We’ve spent a lot of time up north in Mendocino and Fort Bragg, that area, and that’s great, but it’s just different. And this has enough of the Spanish history, the Latino history, an involvement with the Latino culture…Santa Barbara is I think a fascinating place even though it tries to bury that culture a little too much…but I think as a Californian, as somebody who is here and was born here, to me it still represents opportunity and adventure.

And even though it’s not the most business-friendly state tax-wise, it is where the juice is. Everything seems to start here. Not that I’m trying to start a whole lot, but I enjoy the vibe, and I enjoy seeing entrepreneurial spirit and people who are quite prepared to start something. I love the fact that there are no chain stores here. Main Street is respected. Shopkeepers are respected. What a concept. There’s that feeling that people can do something, make a life. Nobody is trying to be stupid rich. They’re trying to make a life and enjoy themselves. I find that very attractive. And I guess in a nutshell I’m very attracted to the topography of the place.

CW: You mention the topography. That’s one of the things that fascinate me, that you can still see the shape of this land. You can still feel its essence somehow.

BR: The thing about the Valley that’s so wonderful is that, even though when 154 came in it kind of cut all the roads up, there are still these rifle shot roads that you see in other parts of the country. You can go through Ballard and start towards the southeast and see how, before 154 was there, it just cuts…you wouldn’t even have to turn your wheel: “Well, let’s put a road here. Everybody’ll get there sooner or later.” I like that.

We had a restaurant in Santa Ynez for a couple of years that was named after the magazine. It’s a chapter that I’ve closed. It didn’t work. There’s just not enough people to support something like that, but it was great fun. You got to see people and they’d come in at the end of the day, they’d have a meal, they’d have a drink, and they’d come back…they’d just want to see who was there. I love that. All the great bars of the West did that. You’d look in….oh, nobody’s here…and then you leave. That sense of community, you just don’t get that in other places. No matter what you do around here, if you do something at the Grange in Los Olivos, if you do something at the museum, one of the plays, you see everybody all the time anyway, but you see everybody there. There’s no need for any giant conversation. It’s just touching base. “You look good, no limps, we’re all good.” That sense of bumping into the same people…I like that.

CW: I like that too. We were at a writers’ group the other day and I was just pondering how many different ways we knew each other, all the interconnections our group has.

BR: I think especially for writers, who are in their head all the time, it’s good to be able to be with other humans, interact, sniff the bushes a little bit. I find I do everything from here, and we have lots of writers who write for the magazine and they’re all over the world, and I don’t mind it, but it’s still nice to go out and actually touch somebody. There are other people out there. But there are also times you have to roll the rock in front of the cave and get things done.

CW: How would you define yourself: a publisher, writer, entrepreneur, horseman, all of the above…

BR: I have reinvented myself quite often, but I know I’m a creative person. I’m not someone who delegates really well. I mean, I do, but I’ve had small businesses and done a lot of things myself, so whether it was in the advertising business or the record business or publishing or whatever it was, I would find the solutions myself. So first I would call myself a creative.

Writing has come to me out of necessity. I was a copywriter and an art director in my past life, and when I started these magazines somebody had to, so I just started writing. And I had some friends who were very good writers who gave me a lot of guidance. So writing is very important to me.

Publishing is sort of a distribution vehicle. Your books and your blog are how you can reach out. I helped with the start-up of a magazine called Cowboys and Indians in the early 90s. It was really designed to be a long form thing; this was at a time when there was a lot of opportunity to get advertisers, to get big distribution… it was kind of pre-internet, which was almost happening, but not yet. So through all of that period I focused on finding advertisers and selling the idea, and it was a business, and frankly I found it really unattractive. It took away from communicating about a way of life that I had real respect for.

I view the Western thing, this cowboy thing, as one of our very few root-based cultures in this country that’s really quite original. It really is based on hope, a set of values, and a handshake. There is a gigantic work ethic in it, for no reason at all, very little payback. Except you fill your day outside, and you get to be with animals, and all of that. That’s a win.

This thing is so counter-intuitive to today. Look at the little newspaper in Santa Ynez doing this giant multi-part story on the end of the cowboy. They have another installment coming out on the 17th. And it’s pissed off so many people who do this, and make a living, and do really well, or well enough…

This “West is dead” thing that I hear…it’s like looking at any kind of story in what I call the civilian press. Anything about a cowboy in the West, and you can be sure in the first five words it’s gonna say yippee ai yay, you know? Or the word “cowboy” is a negative. You describe politicians as cowboys: it’s a negative. They shoot from the hip. That’s coming from ignorance, ‘cause that’s not what it’s about. That’s a stereotype. Today, these people are bankers, they are farmers, they are doctors, they are scientists, they are animal husbandry people…they have to be everything to survive.

John McCarty on Hollister Ranch is a good example. Every time I see him I tell him, you need a bigger hat. This is a guy who’s out in the sun. He looks like a hand-tooled wallet. Does what he does, gathers cattle, in a most unfriendly environment for somebody on horseback. You could be killed any moment. But that’s what he loves, and he does it.

So when I hear about this life being dead, it’s like, “May I say something?” ‘cause it’s not dead. By choice. Nobody puts a gun to your head to make you do it.

But we make it so hard with all of the tax issues…I’m a tremendous believer in stewardship and working with the land in a proper way but when I have armies of EPA who really, and I understand they’re doing their job and have our best interests at heart, but watching the legality of it, the politics of it going on, when really what this is about is individuals trying to feed a very large nation that is growing uncontrollably and we’re making it very hard for them. And I don’t think we want to become an importer nation for basic necessities.

Now does that mean that nobody is aware of climate change? Not at all…but we’ve gotta work with it and figure out how to solve this collectively. And when people are critical of all this, they don’t look behind the curtain and see what hard work it is to do that.

So…I can’t remember what the original question was.

CW: It doesn’t matter. I love hearing your thoughts on these things. I don’t want to interrupt. We’re talking about The American West. Cowboys.

BR: The work aspect…the ranching and farming…is one side of it. The culture side of it is even more important, in my view. The number of makers, the number of craftspeople. the number of people who want to paint a guy on horseback…they want to do that still, and the fact that there’s still an audience for it says something about the basic attraction this has. And there’s all kinds of data showing that when we go into a recession, the imagery of the cowboy is utilized by companies and businesses in advertising because it’s a symbol of self-reliance and stick-to-it-iveness. It’s a singular figure that has iconic qualities in America, and we have this kind of love of the subject. It’s not the movie guy; it’s the guy who’s trying to make a payment on a pickup.

CW: I like what you said earlier: it’s based on hope, a set of values, and a handshake. I think we all have some hunger for that, and maybe that’s why the appeal of it never goes away.

BR: I think the ability to deal honestly with someone and feel you are receiving truth versus perception…sometimes we perceive truth but it’s been spun…real truth is what I look for. Generally we tend to get that from this group of people because they don’t have time to be otherwise, and it just doesn’t fit. You can’t fool nature. It’s whatever you’re handed. I think it was a line in some song by Paul Simon: “I get the news I need on the weather report…” That’s what those people do.

RA: It’s an authentic life. That’s something most people yearn for, deep down.

BR: Especially when there are so many people that are constantly looking down on a screen. Walking through a museum, walking outside someplace, they’re looking down. I mean, I do it too…

CW: But there is a generation now that knows nothing else.

BR: Well, it’s nice to be a pal to everybody, but if you want to be “liked” figuratively and symbolically all the time, if that’s what you’re working towards, versus being authentic and effective and contributory…

We have a generation that is very apolitical. It has created what we’re experiencing right now, it’s created this anger, people who out of hand, have pushed aside a class of people who are politicians because they don’t feel they are getting honest answers. So we bring in the clown car. That’s what we have now. It is a total, complete waste of time. We’ve spent so much money and we have such problems.

My two girls, one’s 26, one’s 21, and we had this big discussion about what the Supreme Court was going do on gay marriage. And I said, of course they’re going pass it, because there’s a couple of people on there who realize that we have way more important problems to worry about than who loves each other. We have forty-two million people in California, and this one candidate wants to effectively deport the entire population of Los Angeles County in eighteen months for his immigration plan. That’s not deportation, that’s genocide. There’s no difference from these third world countries for a guy to come up and say that who is a billionaire. I’m sorry…

CW: No, it’s okay to talk about it. It’s disturbing. And I think it emphasizes even more why we crave authenticity and deeper values and something real in our own lives.

On the subject of the internet and social media, for me it’s a way to communicate, not how many likes or hits I get or how much stuff I sell. I feel like the internet is the best and the worst of all of us.

BR: It creates a level playing field. Everybody’s words have the opportunity to be read. The bad part of that is 90% of them don’t need to be. It’s great that it’s a funnel, but the straining part of the funnel has to be what filter you choose for your distribution side.

CW: Do you still have something to do with the radio?

BR: We have Range Radio, which is an internet radio service. We used to have FM 1410 here in the valley. But you’d have to wear a tin foil hat to hear it. We’re just an internet stream now. The intent of what it was going to be is sort of what Spotify evolved into and what Pandora is, but we create the play list. It has a lot of followers. There’s 15,000 people listening to it at any moment. But like Pandora, it’s hard to monetize it.

CW: Maybe that’s what we all need to do is liberate ourselves from the idea that everything needs to be monetized.

BR: I agree. I’m a believer that money happens. Money to live happens. We were real fortunate, we sold our house in Malibu, and bought this lovely place, five acres. When we first started out, we lived in a one-car garage. If I had to do that again, I could do it right now.

Simply because stuff like this, communicating like we’re doing here, being…and I’m gonna use the word charitable, but I don’t mean it in the way of handing out money, I mean in giving of your time….to be a part of something that’s larger than you, at my age I just figure that’s important stuff. And it's hard for me to be around people who don’t get this.

This Donald Trump thing, money for money’s sake. It doesn’t compute for me. I just can’t see it. There’s a point where it’s too much. Bernie Sanders is starting to look real attractive to me, and I never thought of myself as a socialist. But the needle has gone so far the other way. We’re buying elections. If people don’t see that, well, you get what you get.

CW: What I would like to know is what is your source of strength? What gets you through the hard times?

BR: My family. That’s probably number one. When I met Kristin, I was a studio potter. We ran this studio in Santa Monica called The Pot Farm. It was a great name, especially in the 70s. Kristin ran the front, and I taught classes and did studio work in the back. We got to talking, and it turned out we both liked horses…anyway, after six months, we got married, and over the years, I keep realizing, how fortunate I was to find her. It’s forty years this year.

And the two girls are the same way. I have a house full of blondes. They know everything. They’re all smart.

Family…my father was very important to me. I didn’t really have him until he retired. He was very busy, but a straight shooter. He worked in television.

CW: Was his name John Reynolds?

BR: Yes. He got into television right after the war and started selling radio time in a little office in Hollywood that was a duplex, and all day long these guys with guitar cases would go up these stairs and play, you could hear them through the floor, and come down, and Gene Autry was up above him, and he was buying and selling copyrights. He just did that his whole life. Ultimately my dad worked for him at the end of his career at Golden West Broadcasters.

He was president of CBS and we moved to New York, so it was big stuff, but he was never impressed with all that. He liked the creative side of it. So I learned a lot from him about follow-through.

If I were to get one choice, I would certainly say my family was the biggest influence on me. They’re certainly writers and creators, people like that. Great strength. And it was wonderful to live here, right here, while my kids were growing up, ‘cause I could take ‘em to school, and if anything happened, I was right here.

CW: Can you think of any particular words of advice or wisdom your father gave you?

BR: Passion is the wood putty of life. It fills in the cracks.

The other thing is this: if it takes longer than two weeks to put it together, it’s not a good deal. You know it is a little different now though…because people can’t make a decision.

Be truthful. People smell bullshit, so be truthful. And that’s how he operated.

He did a show in the 60s, and I can remember people would come to the house all the time…this would be 1959, maybe 1960. I was ten. I could hear this typewriter in the living room and I looked around the corner and there’s this guy chain-smoking, and he and my father are talking very seriously and my dad gave me this look that meant you couldn’t go in the room. Anyway, it was Rod Serling, and he was working on a Twilight Zone. The problem was, the show could only be done based on the amount of money the advertising brought in. They had ten thousand bucks for this one week, that was it, so they did this one show where it was just in a dark studio and these spotlights would come on and people would walk into the spotlights and that was it, but the dialog was insane, it was so good.

So he would do things like that. These people would come in, and he’d say, come on…he’d just pull it out of ‘em.

CW: So he was involved in the inception of some classic shows?

BR: Oh yeah. He had his hand inTwilight Zone. Rawhide, and Gunsmoke, and Have Gun Will Travel, and Hogan’s Heroes, and Wild, Wild West. Beverly Hillbillies. So many.

What I saw was his embrace, as a non-creative, of creatives. He realized you had to throw them raw meat and let 'em do what they do. Permission. He was always about giving permission. Try it. Don’t tell me about it. Do it. Write it down.

That was really good. How many times do people say, I got this idea? Are you gonna do it? Have you written it down? Oh...no. Okay, then it isn’t real.

CW: It sounds like you’ve had a series of turning points in your life, but one of my questions is to tell us about one and how you navigated through.

BR: The bad stuff? We had a couple of ‘em. We had some business dealings where I was over my head, and it was through ignorance and being too hopeful. Too hopeful. My dad and I were in this together. I think that was probably the most inspiring thing about it. I mean, I lost a business. I lost a lot of money. He lost a lot of money. And in the middle of it, he had a heart attack. We got through it. He had a new valve put in. And I can remember sitting in the hospital room with him, and it was all over, and we were good, and he said, “You know, I’d do it again.” He said, “We’ve gone a lot of miles. I’d do it again. Don’t worry about it. Just learn from it.” To have a dad that would do that!

But I’ve had a couple of those bad times. How do you deal with it? You have a really good family. You have a really clear view of what your expectations are. And now, at this point in life, you do not over-mount yourself. I cannot ride this horse; I can ride that horse. Know your limitations.

CW: Usually I ask this question at the very end, but I’m gonna ask you now: What gives you hope?

BR: I knew you were gonna ask that. I don’t like being unhappy. I don’t like the feeling of it. And Kristin has been so helpful to me, because I do have a tendency to go to the dark place. I worry. I worry out of responsibility, out of ignorance, out of fear, and 99% of the time, I’m wrong. So when she’ll say you’re going to the bad place, she’s usually right. I took the wrong fork in my road.

So what gives me hope? I am a true believer that life presents tremendous opportunity if you’re aware enough to see it. And I can figure out how the day is going to be when I wake up and I get that feeling in my stomach, that something cool is going to happen today. And I have that still. And I believe that we make those things happen. It isn’t chance. It’s living an assertive life and realizing it is truly a gift every day and you better get after it. Now that sounds pretty noble, but I really do feel that you make your own opportunity, and if you believe strongly in something, that’s the only audience you need.

CW: You addressed a lot of my questions already, but is there any advice or wisdom you’d like to share?

BR: It ‘s your day. It is truly your day. We all have family, we have friends, but we show up at the station by ourselves, and we’re going to leave by ourselves. Everybody is going to get on that bus. So what you do in the meantime is completely up to you. Is it quality time? Are you helping? Are you being more for others than you necessarily are being for yourself? Where is the give-back to the fact that you’ve got a chance? So...what does that mean? Just that the day is there to be maximized.

What can I do to make this entire experience better? I think if there’s something that makes me concerned, it’s the adamant view of people in denial of climate change, the wasting of time there. I finally had this discussion with somebody who just said, “This is what it is.” So I said, “Okay. If this is the way it is, how about you do something so it doesn’t get any worse?” You don’t have to admit that it exists, just don’t mess it up any more than it is.

CW: What was the response?

BR: “Well, I recycle.” And I said, well, good for you. Just have it in your mind you’re not going make things worse.

CW: Do you think we can go beyond that? Do you have suggestions, ‘cause this is something we worry about a lot.

BR: Well, I think these people [cowboys, ranchers, farmers] have a lot to do with it. Because the more we realize we have a population out of control, we keep going like this , we’re going to run out of water, we’re to going run out of food…how do you fix that? I admire that Bill and Melinda Gates are doing. I think all the medicinal aspects of science are wonderful, but we were only meant to live to be about 42. So now when I hear people want to live to be 150, thanks but no thanks. I think if everyone took the perspective we’re will drive less, we’re going impact less, we’re not going waste, we’re just going to be responsible humans, that would help. Self-sufficient, responsible humans. Not greedy. I hate greedy. I hate it. Like this entire methodology of making food so huge that half the population is obese. I can remember in the 50s a good lunch was a bologna sandwich and an apple. What’s wrong with that? Why has that changed? It’s all about money, all about greed.

CW: We need to recalibrate.

BR: Yes, we need to ask what is the value here? What’s important? If having no snow pack in the Sierras is not important, the worst conditions in 500 years, if that’s not a tip-off…

I just think if we were more cognizant and were responsible for our little patch of this planet, which we’re only renting, we’re not going to be here long…we have to take care of it.

But we have to do it in a way that’s non-combative, or it isn’t going work.

CW: True. If you hammer people, that doesn’t help.

BR: Okay, so you don’t see it this way, but how about this? Make it their idea.

I see that from working with animals, especially working with horses. You can use the old way - beat them up and you’re tough with them, and there’s resistance, but if you can work it out to where you open the door for them to move that foot or make that turn and it becomes their idea, it’s a dance. And the two of you are a third greater thing. So how can we apply that as humans?

CW: I like that. It’s a dance, two become a third greater thing.

BR: Now let’s get to the writers I like. I am somebody who searches for a sentence…and I’m thinking you do too, ‘cause you’re a seamstress with words. You do a very nice job of putting those words together. You labor over that.

CW: Too much.

BR: I think there are people today who write, who communicate so beautifully, to where I will read a sentence, I will underline it, and I want to hold it. Tom McGuane is like that. William Kittredge. Wendell Berry. Those are my big three right now. And Ivan Doig. Ivan Doig can tell a story of a family, and humans evolving, better than almost everybody. Ivan Doig just passed away. He wrote This House of Sky. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend it. [Opening a book by Doig]Look at this sentence. It says, “The spaces between stars are where the work of the universe is done.”

CW: Beautiful. Thinking about Western writers, I wonder if Wallace Stegner is on your list?

BR: Yes. And Edward Abbey.

CW: Do you read any poetry?

BR: Yes, I do. I love Bob Isaacson’s poetry.

CW: Oh, I’m so glad to hear you mention Bob’s poetry!

BR: Really and truly. His poetry related to tasks that he loved. It related to ranching, and his observations, or to art.

Wendell Berry does the same thing. He’s the smartest man in the room right now, in my opinion. He’s about 80, and if I were to look at someone who graciously walks through life and lives everything he says, that’s the guy. If I could interpret my life, I look at him, and I think there is an authentic, effective, handmade life. Fools don’t get near him. But his poetry is so light, and so lilting. And it’s held together with gossamer. But here’s this presence. Now that’s power. That’s power. To be able to put an emotion into words.

It’s like great painting. Someone who could go in a room and remember something, and it becomes that. That’s as close to a perfect life as one could have. It’s contact. It’s happening. It’s very admirable.

[Taking out another book] And Teresa Jordan, who is also a poet. She’s married to Hal Cannon, who started the cowboy poetry gathering in Elko years ago.

CW: You can tell a lot about a person by his books….

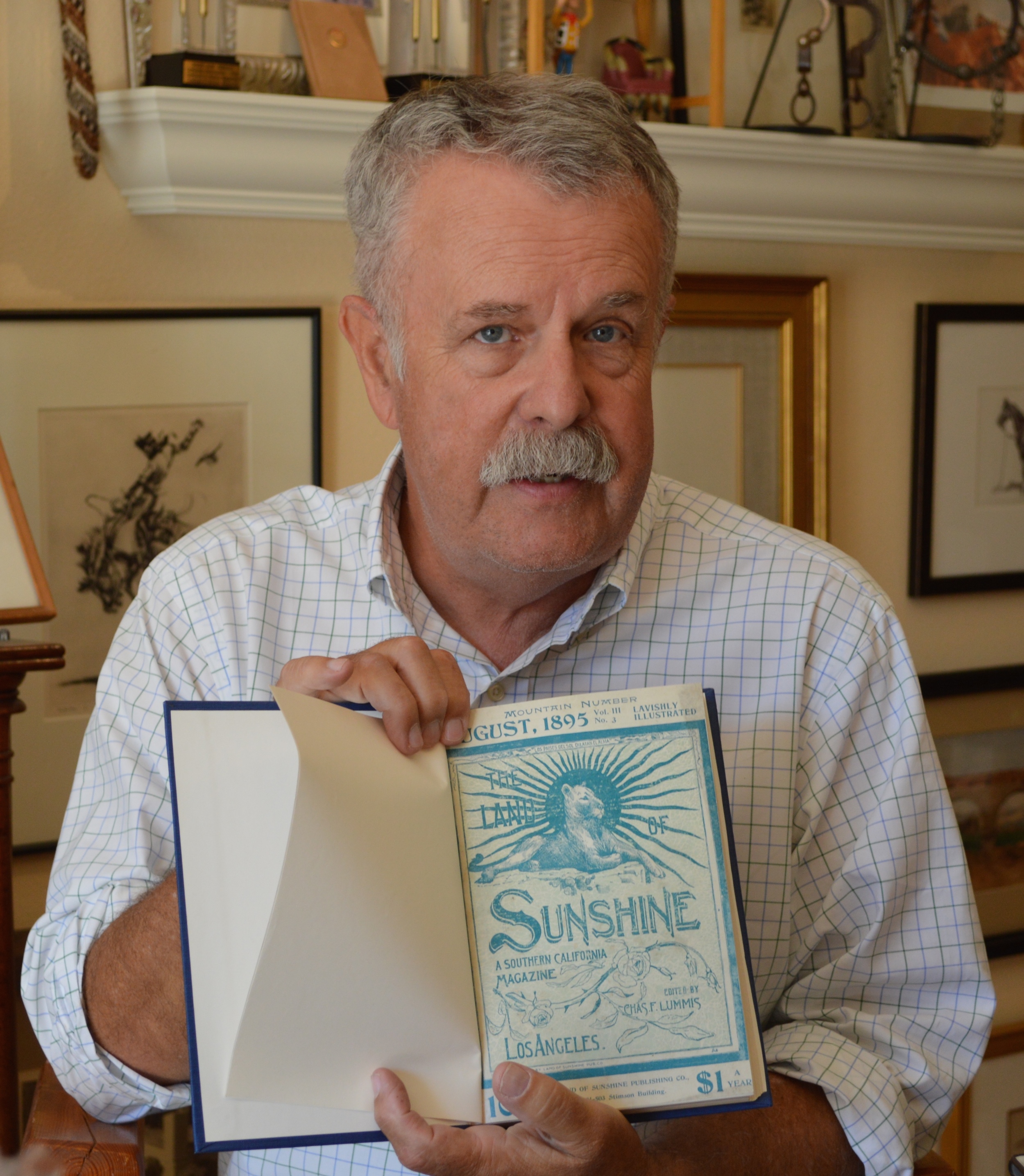

[There followed an impromptu tour of Bill’s research library and taking books off the shelves to show us. One was on Charles Lummis, about whom he began to speak.]

BR: Charles Lummis was a publisher. He was a writer. If he were walking around today he’d have a screenplay in his back pocket. He did a little magazine called The Land of Sunshine that was all about celebrating Southern California and getting people to come. He worked for the railroad and ultimately came out here to celebrate the Southwest. He walked across the country. [Reading from the introduction:]“In 1884, Charles Lummis, a young Harvard-educated New Englander left a newspaper job in Ohio to walk to California.”

He wrote a book called A Tramp Across the Continent. He gave Edward Borein, Alexander Harmer, Maynard Dixon their very first illustration jobs in these magazines…

This is what a fellow reading at his funeral said, and if I could have stolen a eulogy, this is it: In twenty ways Lummis was the most remarkable man I ever knew, his scholarly thoroughness, his appalling industry, his rapier like wit, and the militant heart that never feared to make a foe in a good cause. He finished what he started and he paid for what he broke.”

That’s it. He finished what he started, and he paid for what he broke.

CW: Perfect. Now that’s a way to be remembered.

BR: Before we go, let’s address this internet question for a second, the future of delivery. In the last six months or so, I am seeing a trend, and principally it’s coming from the music business. The highest category of sales in the music business is vinyl. All of a sudden, all these record pressing plants that are out of business, they’re going back in business. First of all, analog sounds way better. Neil Young is right. Streaming stinks. The old analog and your diamond needle, that’s the ball game. The circle comes around.

But what also is happening, I know two people now who are going back into letter press and printing books on broad sheets, simply because there is a very specific niche audience for it. It isn’t everybody, but there’s people who want that.

So the publishing business…and I publish a lot of stuff…the point is, there’s purpose in printing writing. (Until everybody has an i-phone, and I don’t know about you, but I can’t read on an i-phone.) And I’m a paper and ink guy. I like the smell and feel of paper and ink. I just like to hold onto it.

Books are not going to go away. They will become much more specific in how they’re distributed.

For the people who want to read thoughts from A to Z, that’s how it’s going to operate. There’s always going to be a segment of society for whom Buzzfeed is high culture. That’s fine. Sixteen great mustaches, or whatever it is. I’m not there.

Certainly for someone who is writing poetry, who is writing novels, prose, there’s going to be the person who wants to carry it. It’s not going away. And I won’t let it go away, if I have anything to say about it. If I’m a publisher, that’s why.

[At this point, Bill took out examples of the beautiful, high quality books he publishes, including a volume on the art of the saddle and a collection of Arnold Rojas’ writings about the vaqueros, whose rediscovery and publication was a saga in itself. He showed us The Life and Times of A Western Artist by Jack Swanson.]

BR: Jack was one of the founding artists of the cowboy artists of America. He just passed away about a year ago. He was one of those people that influenced me, because he came along after my dad died, and I needed another dad pretty quick. By helping him do this book, it kind of fulfilled that for me. I just helped him put it together and publish it, but it was his deal.

These books are labors of love. I like to work with passionate people who want to get the information out there. Just like you. You know you’ve done it. You’ve communicated. Whether anyone comes back and says, you know, great or bad, or whatever, it doesn’t matter.

CW: To me it’s a message in a bottle. You just put it out there. Someone will pick it up someday. The right hearts will receive it, I think.

BR: There’s your hope, right there. We don’t’ know what is in each other’s heart. But part of the journey is to try to find that out, I think.

CW: Very much so. And also to try to communicate and articulate it while it’s happening, in order to get greater clarity. That’s what The Living Stories Collective is about. I just think life is complex and challenging, and I like to know how others navigate.

BR: It’s pretty much by the seat of the pants. But I do kinda figure, well, this works...let’s keep going. If somebody said, well Bill, why don’t you write a how-to, I’d say, not a chance. I’m an amateur at life. I really am. And to prove I’m such an amateur, I’m so hopeful about it.

CW: That’s what I like about you. First of all, it takes humility to say I’m an amateur. I think the best people would say they were amateurs right up to the end. We’re all learning and improvising, aren’t we?

BR: And for what you’re doing, reaching out, we’re all getting cheat sheets here, back and forth, getting everybody’s ideas.

CW: Thank you so much for being so receptive and gracious about it. I appreciate that so much.

BR: I’m a certain amount of a ham too.

RA: It's a beautiful package, too. Everything you said, from the internet to the cowboys, has this common theme of authenticity.

BR: In today’s world, authenticity is unfortunately a little hard to find.

RA: You have to be intentional about it.

BR: It’s especially what attracts me to these makers, the people who do this stuff. It’s unforgiving. You don’t make any money. You trade. I like that. I like bartering. We need to do more of that. That’s where the value is in things. You’re sharing your own value. But this return at some level of this handmade movement that we’re seeing I think is really positive. I mean, this isn’t the 60s. This isn’t macramé plant hangers. But it’s somebody who’s taking the time to do one thing all the way through, taking it from beginning to end. And that I really like. That’s authentic. When you have something in there that’s of you that someone has chosen and wants in their life. How cool is that?