Growing Up A Little Wild

J.J. Hollister was born in February of 1932 in San Francisco, where his father was working in stocks and bonds. As a result of the Depression, the family relocated to to the Hollister Ranch, where J.J. spent much of his childhood. At the time of our 1997 interview, J.J. and his wife Barbara were living in the old adobe at Arroyo Hondo, a 782-acre ranch located just off the 101 between Refugio State Beach and Gaviota State Park that the Hollisters had purchased from the Ortega family in 1910. In 2001, the Hollisters sold Arroyo Hondo to the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County, where it will be forever protected and managed as a natural and historic preserve.

J.J. invited us into the adobe for a tour before the interview. It is a compact little dwelling that was built in the 1840's. J.J., who was absolutely brimming with stories, pointed to the head of a large-antlered buck mounted on the wall near the mantel and said, "Vincente Ortega was still living here during the earthquake we had in 1976. We came over to see if he was all right and found him somewhat agitated. 'The buck nearly got me this time,' he said. I thought it rather strange to find him talking about an animal. 'And where is that buck?' I asked. It turned out that this buck head had fallen off the wall. It must have given Vincente quite a scare."

During the Mission period, Ortega's ancestors had been granted land all the way from Refugio to Point Conception. Much of this land was later bought by J.J.'s great-grandfather William Welles (W.W.) Hollister in partnership with the Dibblees. The Ortega family was allowed to stay on the land and had a lasting friendship with the Hollisters.

Arroyo Hondo has always been an important site. Much evidence of early Native American cultures has been found here, some unearthed during pipeline digging. At one point, it was a stagecoach stop, and travelers from Santa Barbara to Lompoc would pause at the adobe for lunch. Today it is within the sound of a steady stream of traffic along Highway 101, a busy artery for commerce and tourism.

In the 1850's, W.W. Hollister purchased agricultural land near San Jose, drew up a plan, sold lots to build houses, and created the town of Hollister. When he came down to Santa Barbara, he had a similar vision, and thus developed the town of Lompoc. With a chuckle, J.J. points out a curious irony: "My great grandfather chose interesting sites for his towns. Hollister was built on the San Andreas fault, and Lompoc on a flood plain!"

The influence of W.W. Hollister on Santa Barbara and its northern outreaches is apparent today. He had not come to California for gold. He envisioned communities, and was interested in encouraging both agriculture and tourist trade. He built the pier, a hotel, schools. The family had a home in Winchester Canyon. People passing the Glen Annie exit on the freeway through Goleta might be interested to know that "Annie" was W.W.'s wife and J.J.'s great-grandmother.

In a way, W.W. actually risked his life to promote agriculture. While living up north in Hollister, he became concerned about cattle roaming everywhere and trampling crops. He proposed fencing regulations which would require cattlemen to fence their herds from the agricultural plots -- at the cattlemen's expense. A group of angry cattlemen chased him through town with a rope to hang him! He ran up the courthouse steps and somehow managed to talk them out of it. The fence laws endured and the farmers prevailed.

From 1863 until 1968, the Hollister family owned the Hollister Ranch, then called Santa Anita Ranch. (Jane Hollister Wheelwright, who is is referred to elsewhere on this website and died in 2004, was the sister of J.J.'s father, John James Hollister, Jr.. At the time of this interview she was living, in J.J.'s words, "in the very place she dearly loved as a child.")

J.J. lived at the Ranch from babyhood until 1942, when his parents moved to Winchester Canyon in Goleta. We were interested in hearing some of J.J.'s childhood memories of the Hollister Ranch, and he was ready to share.

The Ranch was a paradise for kids, J.J. told us, with wonders to explore every day. "I had to climb every tree, look through every hole in every oak, peer into every place where a bird might be. I would try to find their nests and learn something about what their eggs looked like, why the birds nested where they did, and then I could watch the little birds being hatched, which was a fascinating thing. I learned birds, and I saw where they could live and how they survived. Spring was the living time at the Ranch. In the summer, we explored around the creeks, rock formations, caves..."

"There were little telephones with cranks when I was young," he told us. "There was one line, and there would be a certain number of rings, and we would connect to the Gaviota store from which there was a connection to Santa Barbara. You had to shout to push your voice through the wire to the store, and then shout even more to push it hard enough to get it all the way to Santa Barbara. To this day, when someone calls me up long-distance, I shout into the phone."

"One day, my father rang the Museum of Natural History to tell them that there was a sea monster out on the beach at Santa Anita. He told them it was important that they come out and see it."

"Now in those days, everyone would amuse themselves by listening in on other people's telephone conversations. And as you can imagine, news of a sea monster was a big deal. You can just hear all the little clicks along the telephone line -- everyone panics! Oh, we were so excited!"

"We went down to the beach. There was the sea monster -- it was very long, and had a great big head, and it was dead. We waited and waited for the museum people to get there. In the meantime, everyone else had come to the beach. We had a little village down there by the time the people from the museum arrived."

"It turned out that the sea monster was a boa constrictor. It must have been put on a ship, died, and was pitched overboard, where it drifted to the shore. Mystery solved."

He told us a tale about a local lion hunter named Charlie Tant, who had a bunch of dogs and made his living by hunting mountain lions around Las Cruces. There was a bounty on the lions because they used to ravage the livestock. Charlie would go out into the mountains and stay for weeks, not returning until he got his lion. Finally, he would bring his kill to the fish and game department, collect the bounty, and move on.

One day, Charlie captured a big old Tom bobcat. He and a friend stuffed the bobcat into a leather suitcase. "I don't know how they managed this," said J.J. "The cat could take you apart." Anyway, they stuffed the bobcat into a leather suitcase, took the suitcase into the Gaviota Pass, left it there, then stood back to watch the fun. Very few cars came through in those days, but finally a big station wagon type car with five or six people in it screeched to a halt. One fellow jumped out, picked up the suitcase, and threw it into the car. Charlie and his friend could see the car suddenly begin to zig zag. Now it stopped, all the doors were flung open, and everyone jumped out. The last one out was a very bewildered bobcat who took off and disappeared into the hills.

In the days when J.J. lived at the Hollister Ranch, there was no electricity, and water came from a well and into sediment tanks. J.J. tells us that folks liked to take a snort of bourbon with water now and then. One day, a visitor to the house was about to do so, but when the water poured into his glass, out came a rat's tail along with it! "All the rest of us figured that if the rat's tail had come through, we'd probably each had a little of the rat.," said J.J. with a laugh.

One of our students, Brooke, asked about fires: "The train would come through and throw out sparks. This was a big danger, especially when the wind was blowing, but I got to help. We would grab gunny sacks, get 'em wet, and our job was to beat the fires out. This worked well on the open places along the tracks, where there were few trees."

"The worst fire I ever recall was the 1956 Refugio Fire. Arroyo Hondo was completely burned out. The trees were just black stalks all the way down to Winchester Canyon."

Brooke also asked J.J. about the kinds of pets he had: "My best pet was caught in the wild by Fred Haught. He caught three raccoons, and one was for my sister and me. We named it Freddy Coon, and he was our favorite pet. He lived with us for three or four years, just like a dog or cat. In the late 1930's we even took him with us in the car to visit my mother's family in San Rafael. At some point he got to biting. We took him back to the ranch and turned him loose at La Cuarta. We cried all the way back to Winchester Canyon."

"Another interesting pet was our pig. My father was out in Bulito Canyon and there was a wild mother pig with a bunch of little babies. The little ones are striped, almost like chipmunks, and so cute! My father rode the mother down, and the baby pigs scattered. He grabbed one of the babies and just barely managed to get back into the saddle with the mother pig chasing him. He put the little pig into the gunny sack he had with him and brought it home. We took it to Winchester Canyon and it became very attached to my sister. She was like its mother -- it followed her everywhere, and became very upset whenever she left. The pig's name was Chipmunk -- we called it Chipper."

"Well, my family was often visited by fancy people from back east in those days who would come to Santa Barbara to escape the east coast winters. One day, one of these friends called and was in the process of making arrangements with my mother to come out for tea. My sister had just left, and so the pig was squealing. Mother said, 'Excuse me, ma'am. I have to put the pig out. It's making too much noise.' When she returned to the phone, the caller said, 'Never mind. I think we'll be busy that day.' The lady must have thought we lived with pigs in the house. I guess we did."

Another student, Adele, asked J.J. what school was like at the Hollister Ranch: "They had the 'Drake School' at the Ranch, and the building is still there, close to the creek, only now it is called the bunk house. There were only eight to twelve students, from first grade to eighth, all in one room -- every size, shape, and form. It was five miles to the school, and it started at eight o'clock. We rode horses sometimes. For the winter, father built a shelter we could sit in, and he'd come for us with a tractor. We had one wonderful teacher. Her name was Ruthie, but she married my uncle and stopped teaching. We used to go down to the beach for recess. Of course, we could never hear the bell from the beach."

Funny thing, we pointed out -- our kids never hear the bell, either, with or without the ocean.

Adele asked J.J. what he did for recreation: "On weekends and summer, we'd spend a lot of time at the beach. No one had a bathing suit. We were all stark naked, riding the waves. And there was hiking, of course. And riding. My grandfather made sure we could ride, but he wouldn't let us get on the big horses like the cowboys had. We were given ponies instead. The one I was given was called Indita. She looked like a black bear with shaggy hair, a cute little thing, but she liked to bite and couldn't get across a stream until she'd gone down very slowly, rolled, and knocked me off into the stream. She could also run away, and no matter how hard I pulled on the reins, she kept going. I wasn't strong enough to make an impression on her. It took me a long time to enjoy riding because of Indita."

"I liked to do other devilish things. I liked to get in the barn, and climb up on the haystacks. There was a big dairy bull. He had a ring in his nose -- and he was so mean! I used to tease him. I also used to hunt for arrowheads at Bulito Beach -- I would spend hours doing that."

"The railroad was fun. If we wanted to get on board we could stop the train by waving a red handkerchief. One time I got to be the one to do it. I remember it coming around Coho and onto the big straight, coming closer, and then I waved the handkerchief, and it was so much fun to see that big thing stop."

"Once a month or so, the kids would get to go to town. We would clean up and dress up, slick as a whistle. I remember once on the way to town, between Cuarta and Alegria, we came upon a cow with bloat. There was my father and all of us in our clean white shirts, but we had to stop and take care of it. We had to stick the cow to let the air out -- not a thing to do in a white shirt. But that was often a part of the journey to town, stopping along the way to care for the herd."

"In 1936 we all decided to ride in the Fiesta parade on our little horses. It was grand. But what I remember most is not the Fiesta but coming back from it, late at night. As we were going down past Alegria, a figure suddenly appeared in front of our headlights, and he was running as fast as a person can run. Then he tripped, rolled down a hillside, and disappeared into the night. We didn't know what to make of it."

"We were isolated at the Ranch, and news reached us late. A day or two later, the sheriff called my father, who was a deputy. The sheriff said, 'There is a hangman in Alegria Canyon. We need your help.' The hangman, whose name was Lee, had come over from the Gaviota store and hung himself with his belt from an oak tree. He had been discovered by a railroad worker. This worker had a lot of dogs, and he loved to go after raccoons at night. That's what he was doing when he bumped into the hangman, who swung back and knocked him down. He was scared out of his wits and took off running. That's when we saw him in our headlights. Well, that solved a great mystery."

" My father had to build a little coffin for Lee. He took his favorite horse, Oso, up to where the hanging was, and Oso was so spooked by the dead man that my father had to lead him back down. This was all big news for us little kids on the ranch."

Brooke asked J.J. what other memories he had from the days of the Great Depression: "I was little, but I felt the Great Depression through my folks. My father was in stocks and bonds. That was one reason we came down to the ranch. The Depression was just what the word said -- people were down, depressed. There were hoboes everywhere. They would get off at Drake or Bulito and my grandmother or the Chinese cook would give them a sandwich. It was a type of fright that lives with you night and day. There was no government help in those days. People were despondent. It shaped my father's life."

Elise asked J.J. what his special place was as a boy at the Hollister Ranch: "There was a little tree on the side of the road near the big house. I found a rope at the barn, tied it onto the tree, and I swung. Whenever a car came by, I could sit up there and watch. Whenever a car came across the wooden bridge, it made a lot of noise, and Grandpa always looked to see who was coming before they arrived."

"And I loved barns. The barns were full of bats, bats in every corner. I loved to throw a rock and get them to fly."

"Sometimes butterflies would fill the eucalyptus trees near where the office now is. I would toss a stone to make them fly. It was so beautiful."

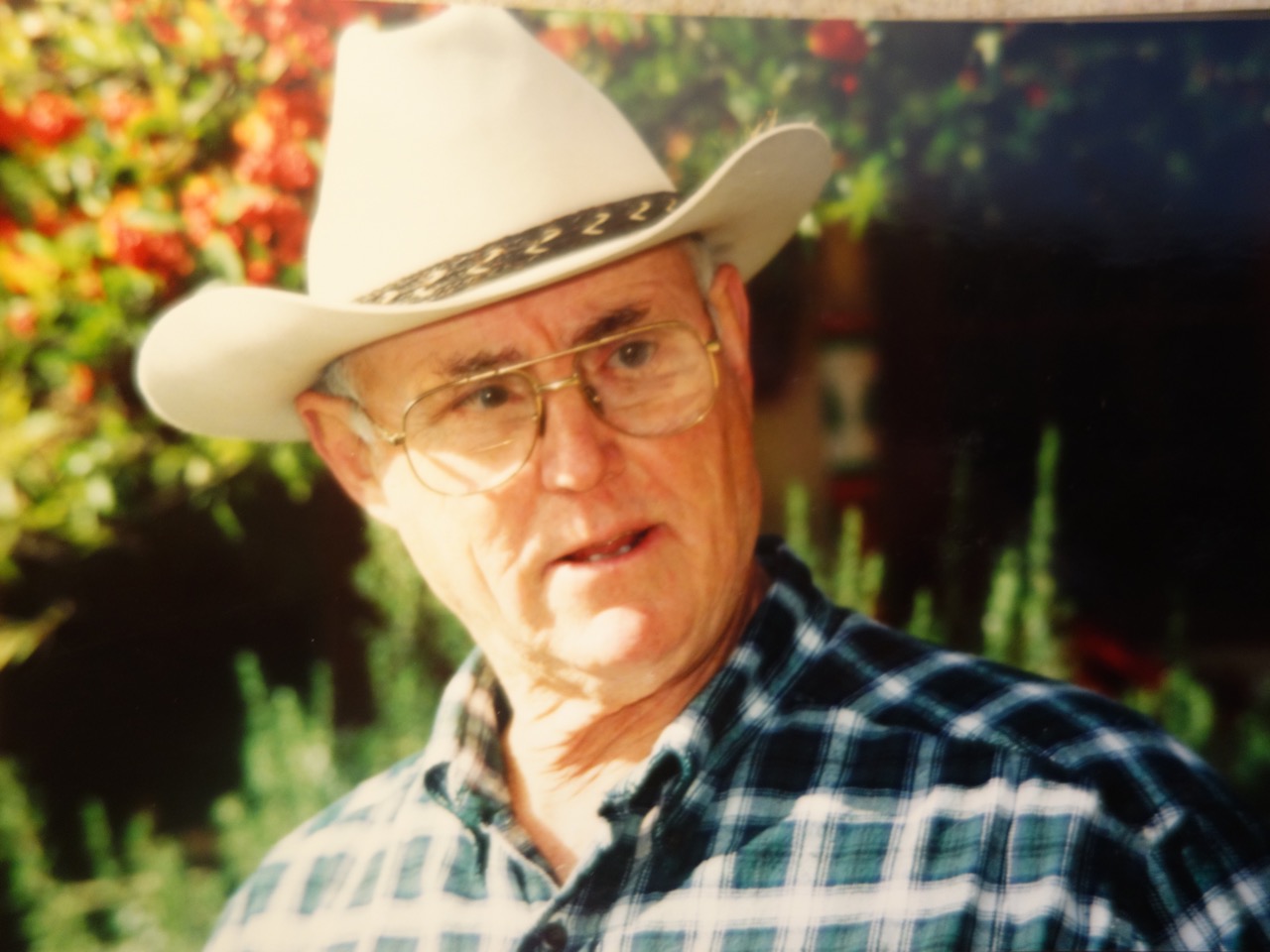

JJ and his sister Cinny-wee

One of our students wondered whether J.J. had a best friend: "My best friend was my sister Cinny-wee (Cynthia). She was three years older than me, and oh, such a tyrant, as older sisters are! But it was just the two of us, most of the time."

"I was thinking the other day about the songs we used to listen to on those little phonographs you'd crank up and they'd play 78s. My sister and I would listen to 'Home, Home on the Range', There are lines in that song that fit the Ranch, 'Where the deer and the antelope play...' and 'Seldom is heard a discouraging word...' Well, the reason there was no discouraging word at the Ranch is because nobody had any information about what was going on! We didn't get a paper and we didn't have radios...well, my father had a great big wonderful radio, but we couldn't get any reception..."

"In your daily routine, you were one with nature and one with places where few people were. Those people who were there, you knew very well. You worked with them and played with them and found things to do...it was a kind of unpolluted, healthy, and uncomplicated life."

Our interview had come to its end; J.J. had a noon engagement and it was almost time to go. He led us first through the citrus orchard, lush with fruit. He pointed out a bench made from the wood of the tree he and Barbara stood beneath when they were married. He showed us a mortar and pestle left by the Indians, and a nineteenth century dagger found in the stream. He lavishly bestowed avocados upon us, enormous round ones, ripe and creamy inside. It had been a wonderful morning.