That Sycamore Tree is My Twin

This visit and interview with rancher A. Dibblee Poett took place in 1997, three years before his death in November of 2000, at the age of 93. He had spent all but the last two or three years of his life at Rancho San Julian, living the life he loved.

November's slightly breathless light drenched the hills and fields that morning as we drove along Highway 1 towards Lompoc. The sixth grade students of Vista de las Cruces School were about to meet and interview the legendary A. Dibblee Poett at the Casa San Julian. One of the few Spanish land grant ranches still owned by its founding family, San Julian Ranch is located just up the road from Las Cruces, where the Santa Ynez Mountains become the Santa Rosa Hills.

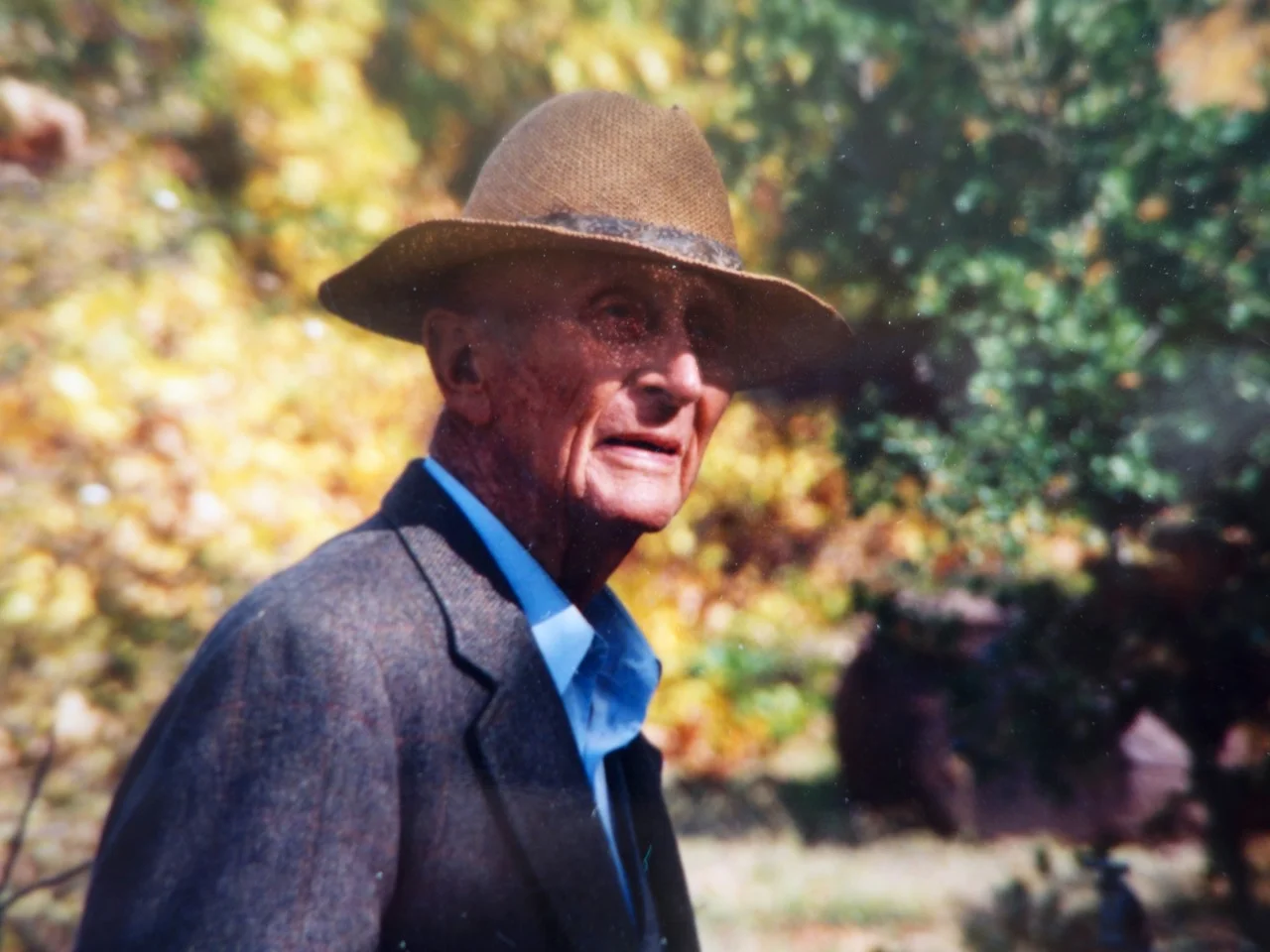

We turned off Highway 1, rattled along a dirt road, and parked in front of the casa. "Dibbs", as he was affectionately called, pulled up in an old Mercedes, his dog by his side. He looked rather dapper, I thought, in a straw hat, tweed coat, and gray flannel trousers. Walking carefully with a cane, he led us into the house.

Those of us who live in the embrace of this nurturing land need to know its history, hear its voice. The ninety-year old Dibblee Poett was a part of this history, and our students recognized the importance of the stories he might share with them. They had come prepared with questions -- kids' questions about best friends, Christmas mornings, school, and special places.

"This is my special place," said Dibbs. "The old house. It has so many memories. When we were children, my sister and I used to ride a lot here. We rode bareback-- very light-- and the horses used to get over the hills very easily. As we got older, we had to put on saddles, and so the hills got steeper than they were when we were young."

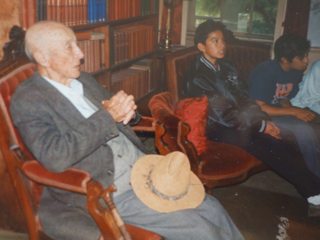

We sat in his favorite room, a room lined with books and paintings and old photographs, a room filled with the past. Pale sunlight streamed through lace curtains and lit upon the flowered wallpaper. There were Victorian chairs with carved wood frames and red upholstery, Oriental rugs worn to threads, and an eccentric chandelier -- "a relatively new addition" -- adorned with crystals in colors like amber and green. There was nothing fussy or proper about the room, and it lacked the muted sadness that one often senses in such places. Yesterday could linger here, feeling safe, laughing a bit. Dibbs looked fondly around the room as he settled into his chair.

"It was too cold to live here in the winter," he said. "A man used to bring in wood. He spent most of his time cutting and hauling and bringing in wood for the ten fireplaces and emptying the ashes out. It took a while to get the house warm because the ceilings are so high, but once it was warm it would stay warm because the walls are so thick. We did stay here in the winter of 1918 during the war when there was an influenza epidemic. People thought they'd come to the ranch to escape the influenza, and then one of our tenants down the road died from it because he couldn't get to the doctor... so we figured we'd better get back to town."

"The ranch is about 16,000 acres now," he told us. "It was 48,000 acres when it was deeded to my great-great-grandfather in 1837. Then they lost it in 1862 after the big drought. It didn't rain for two years, and all the cattle died, so the sons lost the ranch. Then Mr. Dibblee and Mr. Hollister came along, and Mr. Dibblee married the granddaughter of the original owner, so it came back into the family again."

We were all a little awed by the old man. We had been forewarned that he could be cantankerous, but we found him to be gentle and patient. His voice was tremulous at times, and he frequently asked the children to repeat their questions, but he seemed genuinely eager to talk. When he spoke of his childhood, his angular face would visibly soften; he seemed to savor the details of those fine days, as though reliving them in the telling.

"Oh! We climbed trees," he said. "That was one of the things we liked to do, and we never fell. Yes, we used to climb trees, my sister and I, and we would go barefoot, believe it or not, all around, all the time. After awhile your feet get calloused so you can go almost everywhere. We wore great big straw hats, and one day we were walking along and we happened to get into the middle of a patch of little prickelotas ---somehow before we knew it we were into it-- so we had to throw our hats down to get out."

"And we used to ride a lot when we were young. Nan and Frederica and I were each given a horse, horses that were not very good for the ranch hands because they'd been cut in the wire, or something like that. I had a horse once and he had a wire cut, and whenever he was going from home he always limped, but on the way back he never limped."

"One day we were riding and we got into a nest of yellow jackets, and they got all around us. I jumped off the horse and was running around a bush about the size of this room. The bees were following me, and the horse was following me, and I couldn't get away, so I jumped into the middle of the bush!"

The kids wanted to know what kind of wildlife Dibbs has seen on the ranch.

"You name it," he replied. "We've got skunks, coyotes, coons, bears, lions, all kinds of birds, though no more condors, deer, possums, badgers -- everything you can imagine, almost everything. Lots of birds. The animals like the creek -- habitat, water, protection from their enemies."

"Are there fish in the creek?" asked one of the boys.

"There used to be. In the old days, there were a lot of pools in the creek, and there used to be the brook trout, which was very good to fish and eat. We used to like to do that, but they started farming the hillsides, and the pools got filled up, so there aren't many left. They've been bringing in other fish like the rainbow trout, and the rainbow trout kill the brook trout."

Many of the Vista students themselves lived on ranches, fished in creeks, and dwelled in the warm shadows of these familiar hills. They felt a connection to this man, recognizing the kinds of places he had loved. The questions began to come more freely.

"How long did it take you to get to school?"

"It took me - well, we lived in this house, and the school was right down here about a half mile, right there where old San Julian schoolhouse is, so it didn't take very long. My brother used to ride to school from Yridises and it took him about an hour. He'd have to go out to catch his pony, saddle it up, and come to school, so he rode five miles to school every day, and was there on time. Then we moved to Santa Barbara. We lived within a half mile from Roosevelt School and he was always late for school."

"Was our school [Vista] around?"

"No. Vista didn't exist when I went to school. That started when they consolidated the county schools. Long after my time."

"How many kids were in your class?"

"I think there were eight, probably eight or ten. It was a one-room schoolhouse. The school grades were not segregated. It was just a great big long room and the grades were seated all together, each in logical order. There weren't many young children. There were kindergarten, but I don't remember anybody under the age of three or four years old. But the children who came here had to come in buggies and on horseback. There were no automobiles. They used to come from over the hill that way, way down from Los Amoles, El Jaro, Yridises, La Golondrina..."

He spoke the lyrical Spanish names like a chant.

"My sister and I used to come to school from Yridises on horseback and we'd meet friends at the alamo and race with them. We had a sulky cart and the horses pulled it, and we would go along at a fine pace. We used to race the others who had a buggy and couldn't go so fast as we could."

One of the kids asked Dibbs if he had been a good student. He laughed and answered simply, "No."

"Who was your best friend?"

"When I was going to school in Santa Barbara, a private school in Montecito, my best friend out there was a man named Teddy Greenfield. He always beat me in the shooting matches. They were NRA shooting contests and Greenie would always beat me. He'd win the state title and I would be second. But he was my best friend. He later went on to become D.A. in Sonoma County. One day he was driving along the river and his truck turned over and hit him and after that he wasn't very good at the law profession. He had to sell all his books, and later he died."

He paused for a moment. "I had a lot of good friends, though."

"What was Christmas morning like in the old days?" one of our students wondered.

"Let me tell you a Christmas story about my father. My father worked in Santa Barbara while we lived here during 1917 and 1918, during the war; he left Santa Barbara on the train and got off at Gaviota. It was raining, and he walked from Gaviota to here in the dark with his pack of toys on his back. It was a canvas bag -- they didn't have plastic in those days. And so he was walking along, whipped by rain and wind, the bag soaked through, and he was just across the creek down here, and it was very dark. He walked along, and he stumbled over a bull. All of the toys got scattered around, and the bull went one way and my father the other, and so that was our Christmas. We didn't have any Christmas when he got home. All the toys were scattered in the mud."

"How were the roads between Santa Barbara and San Julian?"

"Well, I'll tell you," Dibbs said with a chuckle. "It was a winding road. They didn't have any heavy equipment in those days, and all the work was done by horses, so whenever a canyon came, you had to go into the canyon and out, into the canyon and out. And at Arroyo Hondo, where J.J. Hollister lives, the road went way down the canyon and around that way. It was a dirt road. You couldn't go more than twenty-five or so, and it was dusty -- there was no cement on the road. So it took a long time to get to town from here. We had the Model T Ford; the Model T was about the only car that would navigate through the mud. And the roads were all muddy, no cement or gravel or anything. Oh, it was awful!"

Ted Martinez, our dear friend and driver that day asked how the ranch had acquired the cool red 1950 dump truck he'd noticed on the property.

"I went east and bought some bulls and bought a long bed cattle truck. I bought it in Michigan and drove it back. It took about a week. Then later on, we took off the cattle bed and put on the dump truck bed, which is more useful here because we have to haul rock and gravel and things like that."

One of the Hollister Ranch kids asked Dibbs if he had any memories about that neighboring ranch.

"Some. In the old days, we used to ship our cattle from Gaviota when they had to go to market. We'd drive down the road, which is now the highway, and drive our cattle down to Gaviota Station. A man was supposed to ride ahead with a red flag. Well, there was a Greyhound bus, and the driver wouldn't stop, so the bull and the bus had a conflict. The bus ran into the bull and the bull stood its ground. The radiator got busted and the bus stopped and a woman fell out of the front seat. The Greyhound people sued us but we won the suit because we proved we had a driver with a red flag."

"After awhile we were not allowed to drive cattle down there, not because of this incident, but because there was so much traffic there through Gaviota Pass. Instead, we had to drive our cattle over the hill to the Hollister Ranch. They had a station called Drake. So we drove our cattle over and shipped them from Drake. There was a big corral near the railroad and a chute that went up to the cars. We would manually load the cars. It took quite a long time, but it was a lot of fun. We were always good friends with the Hollisters. Jim Hollister was a good friend of ours and let us drive our cattle over the hills."

"What was it like during the Great Depression?"

"It was terribly gloomy. Oh, it was awful! Cattle prices dropped to almost nothing. Believe it or not, I sold cattle for a cent and a half a pound. Whereas now they sell for 75 or 80 cents a pound. Then, later on, prices went up a little bit, but even up to the time we went out of the cattle business in 1969, we were only getting about 18 cents a pound for beef, and so it wasn't worth our trouble, raising cattle. Too many men, too much trouble."

"How did World War II affect ranch life?"

"All of a sudden the war came along and they needed beans -- navy beans, small white ones, so we started raising beans. And the horses pulled a big tractor. That's what started farming on the ranch -- the war," said Dibbs.

I pictured the men out there planting beans while bus loads of soldiers passed on the old highway heading for Camp Cooke. My father was one of those soldiers. I still have the tiny yellowed snapshots he took from the road of pastoral hills and twisted oak, of cowboys and cattle, of wooden fences and a railroad bridge. They all look so familiar to me now.

"Are there any other questions?" Dibbs asked. He seemed to be enjoying this.

"Why did you close the kitchen?" someone inquired.

"The Chinese man died over there. He died in his room one night. After that, we could never get another Chinese cook because word got around that a Chinaman had died there. We couldn't get any good cooks. The Chinese cook used to have opium poppies growing right out there. The Chinamen used to come and get the milk from the poppies and smoke it. It had kind of a sweet smell coming out from the kitchen, but we didn't know what it was!"

Speaking of smoke, we asked if there had ever been a fire at San Julian.

"Yes," he replied. "There have been fires, but not very many. A lot of times, the train that goes through Hollister Ranch would throw ashes. They couldn't sweep out the chimney because they used coal and the coal caused a lot of ashes in the flume and the flume would get plugged up, and so they'd throw sand in and scrape out the ashes and the ashes would start fires along the railroad. And so one time, around 1926 a fire started at the railroad and came all the way over the hill and stopped beneath the big creek. It couldn't cross the creek down here."

"Sometimes fires are started by lightning, sometimes by bottled water. You take a gallon bottle of water and you leave it out in the summertime and it can start a fire because the sun is magnified by the water. I went down to my farm house and my truck was smoldering from a bottle I had left there. I told one of the tenants to be attentive about it and he didn't believe me. He left a bottle of water on a big stack of new gunnysacks and it set fire. There are a lot of ways to start a fire. Sometimes fires would start from old wine bottles. A few started from lightning, but sometimes the rain would put out those."

'How much of this land have you personally walked and mapped?" asked one of the adults who had accompanied us, a woman fond of hiking.

"I'd say about 60 or 70%" Dibbs replied. "I used to walk a lot. I used to poison squirrels. They were terrible in those days; they were all over the place, and they used to eat lots of feed. So we started a program in about 1930, poisoning the squirrels. There was a blacksmith down here, and when he wasn't shoeing horses, he'd poison squirrels. He used to take strychnine and mix it up with barley, and he would taste it to see if it was bitter or not. Then he'd spit it out. He never swallowed it, and he never got poisoned."

"So I used to walk all over the big hills over there towards the Hollister Ranch, and everywhere, poisoning squirrels. I used to walk a lot. Maybe that's why I can't walk very well now."

Dibbs also covered a lot of ground when the gas line came through in 1926. "I was appointed inspector," he explained, " to see if they were digging deep enough. That was my first job. The pipe had to be buried four feet deep because they didn't want any plows or anything to hit it. I thought I was very important then. But my main job was to fix the fences for them when they'd go through a fence. And all the way between Golondrina and Las Cruces the digging had to be done by hand because it was too steep for a machine to dig it. So they had Mexican laborers dig the whole ditch with a pick and shovel -- and that was a job!"

We were planning to go outside and have lunch beneath the arbor. The day had grown brighter. The leaves of the sycamores were yellow, and there was a stirring autumnal feeling to the air. I asked Dibbs which time of year was his favorite.

"I guess springtime," he told me. "We always liked the springtime, and then we were always sad when the grass dried up. Then my aunt showed me how pretty the dried grass is in the summer, and it is. But it's always the springtime that I love, when the grass is green. And I used to love the winter, too, because I didn't mind the cold so much in those days, or the rains. I'd get out in the rain, because when the green grass came, that's the time I liked the best."

The arbor behind the casa was built in 1910, and Dibbs said that he could still remember being outside with his mother when it was being built. Beneath the arbor, now covered with grape leaves, there were long tables, and the family has held many barbecues and festivities here over the years, most recently Dibbs' ninetieth birthday celebration.

"One year I had a big barbecue," said Dibbs mischievously, "and the grapes weren't very good, so I went out to Lompoc and bought a crate of emperor grapes and hung 'em up!"

"In the summer, the wisteria will take over the arbor," he continued. "They're stronger than the grapes. But the wisteria is beautiful."

Before us stood a tall straight sycamore, which Dibbs referred to as his twin. "That tree was planted the year I was born," he explained. "I don't know whether it's a girl or a boy, but it's my twin." Both twins are firmly rooted to this land.

There was an enchantment here. We all felt it, a sense of timelessness and balance. The kids ran off to play, as Dibbs would no doubt have done with his sisters in 1915. We had a lunch of soup and snacks prepared by Maggie West and Dorothy Schofield, both of whom lived at San Julian and were parents of Vista sixth graders. After lunch, Dibbs sat in the sunlight in front of the porch, on an old wooden bench that had faded like driftwood. Maggie and Dorothy led us on a walk.

We came upon the schoolhouse, just as Dibbs described it -- a white, one-room building less than half a mile from the casa. We climbed the steps and peered into the windows, but the doors were locked. We went into barns filled with antique carriages, dusty and ghostly, and old farm equipment, long unused. Ted admired a 1940 Chevy like one he had once owned. Threads of white clouds wisped across the broad blue sky, and the land seemed yellow and dappled with sun. I thought of how we take our places in its endless cycle, turning back sometimes if we are wise, to listen and remember.

Earlier, we had asked Dibbs what he is most proud of, and he had said, "I would guess it is the fact that we've been able to hang onto the ranch and the house. There are not many places where the old houses stand and the old families still own the place. So I think that's it. We've been able to hang onto it. We all love the ranch."

That love is palpable, and we understood fully why it mattered so much. I cannot express the awe and gratitude we felt at having come tumbling out of a school bus to find ourselves in the nineteenth century. It was as if we had found a path we had not known we'd lost. We walked back towards the house. Dibblee Hoyt sat astride a tractor, readying a field for its next use.

"Come visit again," he called. "Dibbs might live forever, but you never know."

I hoped we would return. I wanted to hear more stories. I wanted to sit beneath the arbor and see it dripping with wisteria. I knew that curved wooden bench would be bleaching in the sun like an empty boat on a sea of light.

- Cynthia Carbone Ward