I Always Got Carried Away

Myra Huyck Manfrina was born in Lompoc on May 27, 1921. "Not in a hospital," she is quick to add, "but a house. It was on Locust and L, and it's gone now, but you can see it right there in that painting on the wall done by my mother, Marie Huyck."

The house where Myra was born, painted by her mother, Marie Huyck

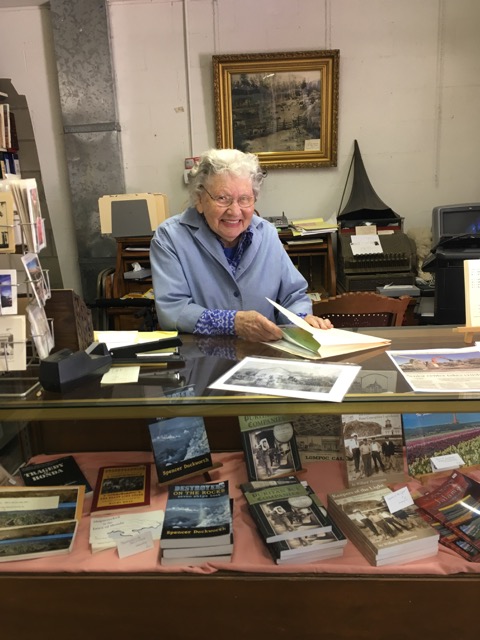

"My roots here go way down deep," Myra says with pride. A vital presence at the Lompoc Valley Historical Society, she is a researcher, genealogist, and historian who also worked as a legal secretary and newspaper writer. "I began as a stringer for the Santa Barbara News Press in 1950," she explains. "I was asked to do a story about Lompoc, and of course I got carried away. The Sunday feature turned into a three-part series."

That tendency to get carried away is why Myra does such thorough and meticulous work. She has researched exhaustive histories about family and town, compiling single-spaced articles and volumes of information dense with dates and details, but always rendered compelling by her distinctively well written narrative. She is a genuinely good writer and a remarkable source of knowledge about the people and events of Lompoc. (In addition to a comprehensive genealogy book about the Huyck family, she has researched and written about the Guidotti, Manfrina, Guerra, Rizzoli, Martin, Kerr, Vail, Muzzall, Pierce, and Hayward families.)

“The wonderful thing is that I still have my mind and memories," she says. "But not everyone I know that’s my age still does. I can’t reminisce with them. There are very few left, but I can’t reminisce with the ones still here because they can’t remember. And that’s sad.”

But the sharing continues. Myra documents and delves into the past for younger relatives, friends, and strangers who contact her for genealogical information or background material for books. She draws upon her knowledge to help fill in gaps and maintain records for the Historical Society, and with this interview she is contributing memories and observations to our Living Stories Collective. She has become an adept user of the computer, and appreciates the relative ease of communication and research via internet. But Lompoc remains her specialty and she is its affectionate scribe.

“Like many other native Lompocans of my era and earlier," she has written, "I have the feeling that Lompoc is mine. I roamed the fields following my dad and my grandfather as they plowed and harrowed the acres of empty ground in town in the 1920s. I rode on their gravel wagons back and forth from Lompoc to the river bed at H Street. I couldn't count the times I spent 'helping' them load the wagons with each shovel full of sand or gravel, or 'helping' them hitch the horses from one wagon to the team of the other so that heavily loaded wagons could be pulled out of the riverbed."

"My territory was on South N Street to the hills, to China Creek to the west, and over to about K Street, to Cypress Avenue. There were hardly any homes in that section then, only the big old high school building at L and Cypress...I think I must have climbed every tree along the way in my wanderings...big sprawling peppers and sycamores, a child's dream for climbing. And I still have a great affinity for the beautiful hills surrounding our valley..."

Myra was an only child, born to Lloyd and Marie Huyck, but she had cousins to play with and wasn't lonely. She was also close to her grandparents, who figure prominently in many of her memories.

“I recall as a child in the 1920s going to Grandma Pierce’s for a chicken dinner, but first a trip to the chicken yard and where Grandpa would chop a chicken's head off with a hatchet, or Grandma would pick one up by the head and whirl it around, a technique called 'wringing its neck'. After killing the chicken one way or another, the feathers had to be plucked off, then the carcass singed in the fire to get all the fuzz and pin feathers, and finally it got to the oven or frying pan. All the men in my family, ancestors and descendants, were and are hunters and fishermen. I can only swat a fly or step on a spider. Forget everything else.”

"On May 1st, called May Day, we would make baskets out of paper and flour and water paste, pick flowers from our yard, or put some candy in them, then take them to the home of a friend, aunt, or grandmother, hang them on the front door, and run away. On the Fourth of July, there were real fireworks bought at Mama Wong's, near the corner of K and Ocean. We would sit on the steps at Grandma Pierce's North L Street home while Uncle Bert Rios and my dad would put up pinwheels on the big tree trunks, shoot skyrockets...the kids could pop long strings of small firecrackers themselves. There was usually a parade that day with lots of flags and John Philip Sousa marches by the Lompoc band. Memorial and Armistice Days, May 30 and November 11, were both patriotic days, with a lot of ceremony. There were tableaus at the Lompoc Theater depicting World War I scenes or patriotic themes, leaving a big lump in my throat. That patriotism instilled in childhood has stayed with me all through my life."

“There were Sunday rides to the beach or over the countryside – endless gates to open and close, flat tires to be changed, and we always took our picnic lunch – there were no handy restaurants or fast food places to buy anything to eat. The only one I can think of was Morinini’s Store at Surf. We could get candy and soda, and crackers and cheese. We went to the Elite Bakery, westside alley corner, 100 block South H, and got a frappe cone, double scoop for five cents. In teenage years I went to Lind's Café after school for a marshmallow Coke. I was skinny then."

"You knew it was spring and Easter time when the men and boys blossomed out in white shoes and gray suits and the men wore straw hats instead of felt ones. There were no electric blankets, you used a hot water bottle or piled on more quilts and wore your heavy flannel bathrobe to bed. You used the sun or the oven to dry your hair, and rubber bands held up our rolled above-the-knee stockings until the advent of garter belts."

"We didn’t lock our house or car doors. Everyone respected each other’s property. We washed dishes and clothes in hot water, and it was pretty grimy at times. But the water was healthy to drink. We ironed all our clothes. And we used ink…pens with pen points dipped in a bottle of ink or inkwell. Many times the ink blotted and splattered and we’d have to do the paper over."

"Music and lyrics were lilting and romantic, not graphic and blaring like today. We listened to radio programs of music and plays, using our imagination. At school dances we danced in our partner’s arms and only cheek to cheek when Miss Bowen wasn’t looking. It was an age of innocence. Every Saturday night there was a dance at the memorial building. We even had dance cards. That's one thing we did in Lompoc. We danced."

"Everyone had a good time. No money, but a good time. We could roam into town even at night, feeling perfectly safe. I wouldn't want to go back to living the way we did in the 1920s and 1930s, but I miss that wonderful, uncomplicated peace."

In March 1942, Myra married Walter Manfrina, whose main occupations, according to Myra, were farming, flower seeds, and his favorite, fishing. As Myra tells it, Walt's love for fishing probably started when he was just a toddler sitting on a creek bank near El Jaro (on the San Julian Ranch) watching his older sister pull out trout after trout with a string and hook attached to a willow stick pole.

For a brief time at the start of their marriage, Walt and Myra lived in an apartment in Long Beach, and Walt was drafted into the U.S. Army Infantry in 1944, when their first son, Barry was a baby. (Another son, Bob, was born in 1947.)

Myra and Barry went back to live in Lompoc while Walt was gone. Myra's father worked in the Post Engineers at Camp Cooke when it first came to Lompoc, and her mother and Myra sometimes went to the Walnut Street USO to serve refreshments at dances and help out in various ways. "I danced with the servicemen, and we'd share stories," Myra recalls. "I'd tell them about my husband serving overseas and they would talk about their wives waiting for them in faraway homes. There was a recorder there for everyone's use, and I went with friends, taking Barry when he began to talk, to record his voice. We sent the little records to Walt in France."

Walt served honorably in the European Theater of Operations, taking part in the Battle of Hurtgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge with the 1st Infantry Division. He was hospitalized twice and awarded a Purple Heart for his service, returning home to Lompoc in 1946.

Walt was soon hired by Burpee as a greenhouse manager, and the Manfrinas contentedly settled into life in Lompoc, near friends and relatives. They had been married for seventy-two years when Walt passed away two years ago at the age of a hundred. "Seventy-two years. Isn't that wild?" says Myra.

In many ways, it's a looking-back time of life for Myra, but she stays busy and isn't a complainer. "I've always had a positive outlook," she says. "I'm able to rise above it, somehow or other. And I love to do things for other people. There's a satisfaction in that."

In addition to her work at the Historical Society and on the computer at home (which is also a fine base for an occasional game of solitaire) Myra expresses her creativity by transforming bits of broken jewelry, porcelain doll faces, and bric-a-brac into unusual objects d'art arranged within small shadowbox frames.

"You just have to do your best and keep going," she tells me, more than once.

As is my custom, I ask Myra what advice or life wisdom she would like to offer. "I knew you were going to ask me that," she says, "and I wrote it down." Myra's basic rules:

Take pride in what you do.

Do the best you can.

Volunteer.

Have a hobby and a goal.

I also wondered if she might want to mention anyone in particular who had an influence on her thinking. Her grandparents came to mind.

She shows me an album inscription written by her Grandpa Pierce:

Count that day lost

whose low descending sun

views from thy hand

no worthy action done

Myra's days continue to be filled with worthy actions. She confesses that she sometimes sees Lompoc as it was, not as it is, but her gift to the community is ensuring that it does not forget its past.