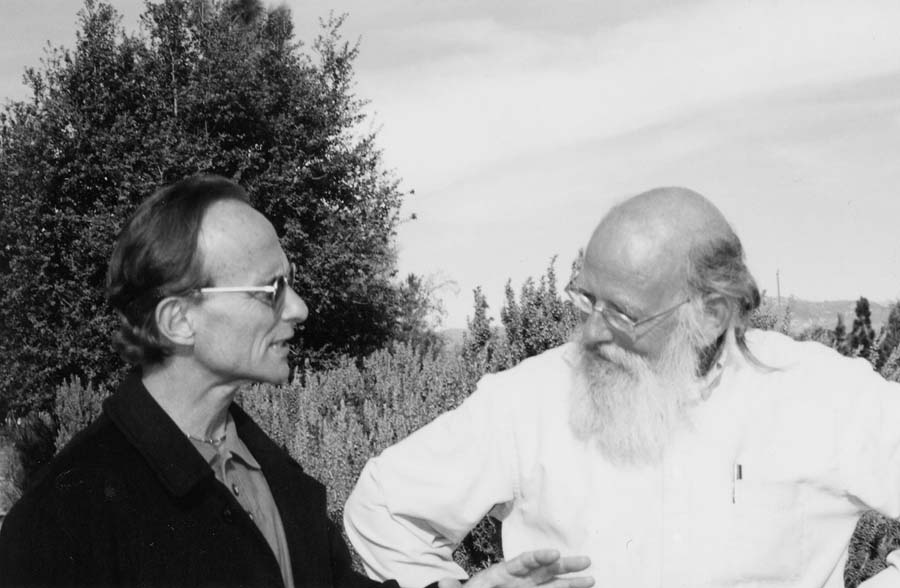

A beloved physician in the Santa Ynez Valley, the remarkable Dr. Netzer was also instrumental in the creation of the Family School, Friendship House, Country Medical Clinic, and the Side Street Café. Then, at an age when most people think about retiring, he moved to a remote village along the Amazon in Bolivia and founded the Rio Beni Health Project. Lou understood that our lives are everywhere linked. His work was about the palpable power of the love unleashed when people come together and realize their connections and capabilities. Lou spoke to students and teachers at Dunn Middle School in 2001, shortly before he was diagnosed with the cancer that was to claim his life on October 10, 2002.

I happen to think that relationships between people – from friendships to love – are far and away the most important thing in the world.

THERE HAVE BEEN MANY BEAUTIFUL MOMENTS

Excerpts from Lou Netzer's talk at Dunn Middle School in Los Olivos, California in February 2001:

“I just turned sixty, which was an interesting experience. I was born on July 15, 1940 in Washington, D.C., but a lot of people know me here, and the Valley is the home I come back to. I lived here and was a doctor here for thirty years, and I was very involved in the community. Now, for the last five years, I have lived in South America — in Bolivia — and I started the Rio Beni health project working with the Indians in the Amazon. I come back here two months out of every year to give talks and raise funds for the project. I’ll be going back in March.”

“My big dreams early in life were to either be a doctor or a writer. I decided to be a doctor because I felt that doctors were out doing things, and writers wrote about them. I didn’t make the decision between the two until I went to college. I went to Duke and I majored in English because I liked to write. I was really in a hurry to get out into life, and I left Duke after three years and went to medical school in Chicago.”

“I absolutely love being a doctor, and there are two reasons: one is that you have the privilege of being with people at the most intimate times of their lives. You are with them when babies are born; you are with them when they die. You are with them when they are ill and vulnerable. You get to be a part of it all. In a sense, you are the honored guest.”

“The second thing that is fantastic about being a doctor is that you can do so many things with it – you can practice anywhere in the world; you can teach… you have so much choice.”

“So I decided to be a doctor. But I also write. My poetry is very personal. If I’m going through a period of self-doubt, I write about self-doubt. If I’m madly in love, I write about being madly in love. I don’t just write about the scenery or nature, I write about my inner life. For example, I wrote a poem about sitting in a restaurant with my son — being disconnected and far away, and then connecting with him, drinking a beer together before we separate again. We sit and talk and try to catch up on all that’s happened in our separate lives, and then say good-bye. There’s a misty rain outside the restaurant, and he turns and waves, and yells, ‘I love you.’ Those kinds of things…”

“I’m very close to my kids – my daughter is thirty now and finishing medical school, and my son is twenty-three. I miss them terribly. If someone were to ask what is the saddest thing about my life, it’s the fact that I’m far away from being involved with my kids.”

“My parents were both from Eastern Europe and couldn’t read or write. I was one of two children. My brother, who just died a few months ago, was older than I was. I was my mother’s shining light. She loved me very much. My father, on the other hand, was distant. I was never beaten — he was okay — but we just weren’t ever very close. I don’t really think he knew how to love a child.”

“I was born Jewish. I don’t have any prejudice against religion, but I don’t practice religion. I’m not sure if I believe in God, but I have a lot of faith in life.”

“My mother died fifteen or twenty years ago, and we always had a very good relationship. But I am embarrassed to say, as close as we were, I never thought about her again after she died. Never. It amazes me. And I’d say that I feel badly about it, except that I don’t, because I know that we really loved each other. Maybe it’s about my level of being detached. I don’t know. I took care of her when she died. But I never, ever thought about her again. It was a very complete ending.”

“But the last little bit of the story is that just about three months ago, I had a vivid dream in which she appeared — first time in twenty years. I asked her, ‘Mom, do you mind that I haven’t given you any thought?’ She said, ‘It’s no problem, no problem.’”

“The story about my dad is that we were never very close. We weren’t rich, certainly middle class, but my father was a greedy man, or at least that’s the way I saw him. He came over from Europe very poor, and he made some money by buying some land and building some little shops. But I think that what I learned from him when I was young is that money is evil — which is obviously not true, but it’s the message that I got. If you had money, you became bad. So I have been involved in so many things in my life, but every time I get close to making money, I always choose to back out.”

“But there’s more to the story about my father. One of the things I started when I lived here in the Valley was Friendship House, and then, a few years later, we added the Alzheimer’s residence. My father was living in Florida at that time, and he had no one to take care of him. He had no friends. I went to Florida and brought him back here to Friendship House. He lived there for seven years, until he died in 1990, when he was 90 years old. And after all that time, we got to be best friends. We had so much fun together in those last seven years! It was wonderful. When he died, my life with him was very complete. It was a great ending. And what we both realized was he thought that I was crazy, and I thought that he was crazy, but we could still love each other anyway. It was a marvelous ending.”

“I like remote areas of the world– exciting, challenging, simple. About five years ago, I sold my practice of medicine, and I used to own a café in Los Olivos, called Side Street Café, a really popular, wonderful little place. I sold everything and decided to travel the world, but went to South America and fell in love with this particular place. I don’t live in the town, I live in the jungle – I built three thatched huts. I live in one of them, and I have residents, and doctors, and friends who occasionally come down and stay in the huts with me, and a big dining hall, and a kitchen. The town of Rurrenabaque is about a half hour by boat, but when I arrived in the town I became enchanted with it. It was like a town out of the old American west, very rugged, very vibrant, but from the Indians’ point of view – Bolivia is the only country in South America where the majority of the people are Indian, so it makes it a very interesting country, a very poor country. Rurrenabaque was this jungle frontier town, very exciting – you could just imagine seeing a western with the saloons, and places like that, but also, the people who came through there were remarkable. There was a man who came through when I was first there who was walking around the world, Nike was sponsoring him – an environmental protest of sorts, and there was somebody else who had been living in New Mexico and dropped out, a handful of Europeans, artists, so it’s sort of like a community in this remote area of the world, but it kind of has its own magnet of attraction. So I decided to stay there, and I wanted to live in the jungle by myself for a while, which I did before I started the project. I wanted to play Thoreau. I wanted to play Thoreau and write for awhile, then start the project. So I never made it around the world.”

“Most everybody there speaks Spanish. There are three different Indian tribes: the Quechuas, who are the descendents of the Incas, Tacana, and the Tsimane' Most speak Spanish, Tsimane' may not, but a lot of them don’t come see the doctor, they see the witch doctor, the shamans. Spanish gets you by. My Spanish is still terrible. I think I’m dyslexic in languages.”

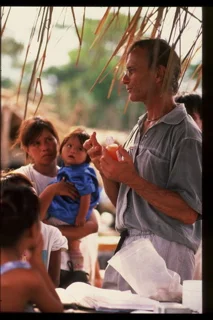

“And there have been many, many times when the Indians have expressed thanks and gratitude. The people are just great. And they love the project; they love having an American doctor there.”

“I love living a simple life. The diet is rice, meat, and vegetables. I have a little gas stove – I live by kerosene and candlelight — but I have a gas stove and fridge, and in the evening I have a beer, listen to the birds, look out over the river, and watch the Indians going up and down the river as the sun sets. The thing that is most amazing is the diversity of animals and plants in the Amazon. Butterflies –you see butterflies like you would see in a psychedelic movie show, gorgeous, fluorescent greens and blues. And once I saw a panther. That’s the most wonderful thing I’ve ever seen. He was down by my shower one afternoon, and he was magnificent. He was long, black, and so graceful.”

“There are snakes and spiders, too. Unfortunately, a lot of the spiders are poisonous, and that gives me the creeps because I’m not a very brave person. One time I actually found a snake in my cabin. It’s a good thing I was alone, because if you had taken a movie of me trying to get this snake out, it would have been a comedy. I haven’t overcome my fear of snakes; I just try to avoid them.”

“The walls of the huts are of bamboo, and the roofs are thatched. The roof is the most important thing because of the heavy rains. The quantities of water are unbelievable. 20% of all the fresh water in the world goes through the mouth of the Amazon every day. The rains are heavy, and they last so long! As a matter of fact, I just spoke to my friend Antonio this morning, and my clinic is under water right now.”

“There have been many beautiful moments...many moments...okay, I'll give you a good moment. The town of Rurrenabaque has a problem because to get there, the only road in northern Bolivia out of the capital of La Paz, is a dirty, pot-holed one-lane highway that goes the tour guide books call 'Death Road’ because you go from 12,000 feet to 1,000 feet in a matter of six hours on a one-lane road underneath waterfalls. It was in such terrible shape where it enters the town, the mayor decided to close the road until the government promised to fix it up. So they put up a barricade and blocked the road, and all the people came out and they were sort of ranting and raving about the road, and preventing anybody from going in and out. I had two medical students with me at the time...I go up and down the river on a boat every other week, and alternate weeks, I go up and down the road in a four-wheel drive vehicle. And we drove up to the blockade and the mayor of the town announced that ours would be the only vehicle permitted to go through the barricade to get to the villages. That was a wonderful feeling. We just drove through and all the people cheered. Moments like that are very nice. But there's lots of 'em.”

“You have paved roads here. You have no idea what cement means in Bolivia! Imagine a life without cement. When they build a little piece of a road or a piece of a bridge, they hire a hundred Indians and get wheelbarrows, and mix the cement, and they’re like ants working. It takes months to build a little piece. Then I arrive in the airport at any city here, and here are these freeways and bridges, all of cement, and I stop and ask myself, how many Indians would it take to build that? You have no idea how much we have!”

“Thievery is definitely a problem there. Once I had my motor stolen, and the people in the village were upset and offered a reward to get it back. Because there was a reward, people were very motivated to find it for me, and they went to the shamans for answers. Somebody brought me a plate, and a shaman put some coca in the plate and boiled it, leaving an imprint of the coca leaves on the plate; then the shaman read the markings. There was a little circus in town, and the shaman said the motor had been stolen by the people in the circus. There is the tent, she said, and if you go to it, there will be a big truck in the corner, and inside the truck is the motor. Antonio and I snuck around, and sure enough, just as she said, there was a truck. We opened the truck, and there were two huge, voracious lions. No motor.”

“On the other hand, the shamans have done some rather remarkable things. I have an Indian who collects medicinal plants in the jungle, so I can offer people either pills or medicinal plants. I’ve seen them do some pretty amazing things, but I don’t have a strong opinion one way or the other. It’s part of the culture, and I support it.”

“If you were to ask what is the most wonderful thing about being there, I would say ‘simplicity.’ I love living a simple life and I am always amazed now when I come back here to see the difference. This valley is so beautiful, and life is so easy, and here we are with an energy crisis, and yet your lights are on, you have hot water, you have all this stuff. My life there is simple. No telephone, no electricity, no credit cards. I miss some of the comforts periodically, but I love it.”

“The people in Bolivia live a very simple life. Very few have jobs. Most grow their own vegetables, hunt and fish for their own food, and that’s what they have. They aren’t lazy; there are just no jobs. It’s changing a little; tourism is beginning to make a dent, and that gives people jobs. Everyone wants to learn to speak English.”

“I don’t want to give the picture that they’re all happy people. The young boys are like Tom Sawyers. They sit by the river, they fish, they hunt, they crawl through the dirt and play with knives. They truly have a wonderful time. At some point, they reach the age where they have to work –whether it is nine or ten, life gets to be very hard. But I don’t think the people there are any sadder than we are, and they certainly don’t have any more problems than we have here. So the point is that having all this stuff, we’re as happy as they are and they’re as happy as we are, so having things has not made us any happier. It’s just made life easier. It doesn’t affect our minds and our spirits.”

“The Rio Beni project is essentially a boat and a motor. We go up and down the river and visit villages about six or eight hours away. So we do that two or three days a week, and every week I have a clinic in the town, and then every other week we go by four-wheel drive vehicles up and down the road. It’s basically about being a doctor, but in truth, just being a doctor by myself would have very little effect there — you save a few lives, but you don’t do a lot in the long run.”

“Fortunately, we’ve been very successful getting support. This next year, an organization will be sending someone down to teach the villagers how to teach health care. Every place will pick out two of the Indians, and these Indians will be taking a course about how to administer their own health care, and basic principles of health and medicine. Just the simple act of washing your hands! If they just started washing their hands after going to the bathroom or before eating, they’d probably eliminate 20 or 40% of the problems. Little, simple things like that, and yet it is like pulling teeth to get them to change. They are very earthy; they are outdoors all day long. Just teaching prevention and how to diagnose things on a simple basis is going to have a more lasting effect.”

“Another organization has donated funds so that we can send one Indian a year to medical school in La Paz, and three or four to be trained as nurses. There is also an emergency fund so if people need to have an operation, they can get to La Paz, which is 200 miles away.”

“The most common diseases are infectious diseases. Their water supplies are not very clean; there are diarrheas, amoebic dysentery, staph infections, all kinds of parasites, and many people have worms. Tuberculosis is very common also.”

“The worst thing I had was heat stroke. I am out there with a machete almost every day — the jungle grows very fast so I have to cut it back to keep it out of the garden. The Indians there were helping me build a field to grow rice and bananas, things like that, and I was chewing coca. The coca plant is a marvelous medicine — it’s not dangerous or addictive at all. The Incas called it the plant of the gods, and it has remarkable effects. It helps you concentrate, and you don’t feel the heat — you just work, all day long, all day long; you don’t have to stop. But I forgot that living south of the equator in November, it’s summertime, and so I worked all day for a couple of days in the field, and that’s how I got heat stroke. That was the worst, I was down for four days with a high fever.”

“I think the most profound change I’ve seen here in the Santa Ynez Valley, aside from the fact that there are a lot more grapes, is the level of materialism. Everyone has so many toys, from computers to cell phones –everyone’s on e-mail, everyone has big televisions, DVD, and stuff — it’s unbelievable to me to see the level of wealth here. And I don’t think it’s making anybody any happier. People are doing well, everyone seems to have a job — it’s great in certain respects, and I’m not saying it’s bad. But it’s the difference that I perceive.”

“To give you an example, when I was living here, if you had a magazine about Santa Ynez that put people on the cover, they would have had the head of a vineyard, or they might have had a farmer, or the mayor. Now, on the cover of the magazine you’ll see Fess Parker, Kelley LaBrock, John Forsythe…relatively well-known actors and entertainers. So what I see about the valley now is a lot of more glitz. It’s acquired a little of Los Angeles or Hollywood– maybe that’s what the valley represents now, and maybe that’s what it wants. I don’t have a great feel for it, but I know that land is certainly much more expensive!”

“I’m part of the culture. If I lived here, I’d probably have some of the same toys. But I am a little intimidated. And as for computers, I’m basically a non-technological person; I barely know how to turn one on. I think technology is fantastic, and you need to move ahead with it, because it offers so much…but I also think that as human beings we have a tendency to bring out the worst in things. Science discovers nuclear energy, and the nuclear bomb appears. Televisions are developed, and look at some of the crap that’s on. Computers? They’re fantastic, but then young people are figuring out how to make bombs and get guns and things like that. That’s a real problem. I worry about what is on the Internet. I’m not a close-minded guy, but there is some awful stuff. The issue of freedom of communication is a complex one. We live in a country that is so free, and so individualistic, but you have to be responsible for that in some way. I sometimes think that what our country and our culture has done is give a lot of freedom without the sense of being responsible for it.”

“I happen to think that relationships between people — from friendships to love– is far and away the most important thing in the world. With all the good that computers do, I’m concerned about people having dates on the computer, getting married on the computer, having sex on the computer…Maybe for somebody who is shy, that’s great, and there’s a lot of good to it, but I would be very afraid that people are gonna start having their relationships more on a machine than face to face. I think that would be a huge loss. Not just you, but your kids, I wonder how they’re gonna have their relationships.”

“I’m a mild-mannered person. I never get angry, but when I have an idea, I am very determined. We started Family School because my daughter was bored. My wife and I wanted her to go to a truly great school that was out in the mountains and focused on the environment, and so we created one. I felt that older people needed a neat place to go instead of a nursing home when they could no longer live alone – and so we created Friendship House. Then we started the Alzheimer’s home, because if you mix people with Alzheimer’s disease and regular people who are just old and frail, it’s a disaster — the old timers look at the people with Alzheimer’s and it’s terribly depressing to them because they mistakenly assume that’s the next step. We were one of the first to put the people with Alzheimer’s in a special home, to acknowledge that they needed to be by themselves, but to create a place where there was a lot of love and caring.”

“I started Side Street Cafe because I have a passion for democracy, and I feel that people were getting all their information from television and radio, which are biased — people need to have more human interaction with each other. I have no interest in the restaurant business. The main idea was to create a place where there would be forums, discussions and debates. I knew a lot of people at the University of Santa Barbara, and I knew people from Hollywood, and so in the little town of Los Olivos, we had all these fascinating people and great stars coming and talking about everything from love to terrorism. People loved it! They loved to get together and share ideas. High school kids would come once a month and have a debate. It was absolutely great. Some of the debates were about sensitive things like marriage and divorce. People talked to each other about what marriage meant to them, what divorce meant to them. Sometimes they got mad. But they talked to each other. It was wonderful.”

“I’m obviously project-oriented. I like being on my own. This project in Bolivia…even though there is an organization called Direct Relief that helps me a lot, I’m still on my own. I don’t have to do any paperwork, and I don’t report to anyone. People know me here, and I can come back and give talks, and they donate money, so the project goes on. The valley is wonderful; people are well off, and so willing to share what they have. I don’t think the population of Santa Ynez is particularly interested in Bolivia, but they know me, and they know I’m relatively honest -I have been known to lie occasionally -and it’s a great time to be doing something like this. I can take advantage of my past.”