A Nineteenth Century Man

I interviewed John Wheelwright on October 23, 2016 at the Hollister Ranch in the very house where he had spent a portion of his childhood living with his grandparents, John James Hollister, Sr. and Lottie (Dot) Steffens Hollister. He generously shared his memories of the Ranch as it was during the 1940s, reflections about the changes he has witnessed, and a unique perspective on the vanishing agrarian life he knew.

CW: When and where were you born?

JW: I was born November 7, 1934. In about two weeks I’ll be eighty-two.

CW: You look great.

JW: Thank you. I look okay on the outside. The inside is going to hell in a hand basket.

CW: And your full name?

JW: John Hollister Wheelwright. Using the English tradition, the mother’s maiden name becomes a child’s middle name. But for the fact that my mother was of the feminine gender, I’d be a Hollister like the rest of my cousins, and I assure you I’m just as much a Hollister as they are.

CW: What was your place of birth?

JW: The family house was at 91 Oakley Street in Chelsea, which is a suburb of London. I was actually born in a lying-in house, which is what they called them then. It was where ladies about to deliver went to have their babies, staffed usually by nurses, not doctors. Doctors were called in an emergency. It was about three blocks from the family home. I think it was St. James Maternity, or something like that. I don’t think it can be easily tracked down, because a doodlebug took it away a few years later. A doodlebug was a flying bomb. It was wartime.

The Blitz had begun on England by 1940. Germany was sending bombs over to land on London, and a lot of the children were being sent out of London because of the growing menace. My parents were doing the thing of the day, kinda farming their children out here and there. Dad had a commission in the RAF, and he would have stayed. He had trained to be a doctor and was going to be flight surgeon. But Mum...in England, it's not Mom; it's Mum....said she’d had enough of it.

We got on the U.S.S. George Washington, built in 1914, just ahead of World War I, but it was an excellent ship of the day. Apparently similar in size and built by same shipyard, I think, as the Queen Mary. I’d heard it called a sister ship with a boy’s name. I’ve only seen one photograph of the George Washington.

We had an interesting trip zigzagging across the Atlantic to avoid submarines with torpedoes. While America was not yet in the war, Germany was busy sinking anything that came out of England.

CW: What a moment in history! I realize you were very little, but do you have a memory at all of being on that ship?

JW: Only very slightly, just a big ship.

CW: And you have an older sister?

JW: Yes, I have an older sister, Lynda. She lives in Brooklyn, Maine. I was six and Lynda nine when we went to live with our grandparents. Lynda was quite a bit more self-sufficient, but it must have been a little rude, to be honest, for my grandparents to get two children. We did have help, ultimately. A woman named Edith Annis came forward. She had been a nanny to many of the Hollister children. My father said that in another time, she'd have been a doctor. She was a very skilled, intelligent woman. She lived into her nineties.

One amusing little tidbit: when we all landed in New York in the fall of 1940, they wanted to get me to the coast with all due haste. I don’t know whether Lynda was with me or not…I kind of suspect not. But they put me on a DC3 Sleeper. Are you aware that they ran airplanes with sleeping accommodations in the 1940s? Now they’re doing that again. But the DC3 could only fly about 600 miles and they had to touch down for more gasoline. So I flew across the country in that, and there were Grandma and Grandfather. We got in Grandfather’s Mercury and went to the Ranch. [snaps his finger] Just like that.

John's Grandparents: Lottie and Jim Hollister

And so I had this transition from jolly old England, with very settled country life in Wittenham, probably to Southampton, got on a liner, probably four days to cross the Atlantic, probably another twenty-four hours to fly across the U.S., and then the Ranch.

CCW: So they literally put you on this plane and sent you off?

JW: Probably just the way they send immigrant children off. You get one of those labels with a string on it, write down the name and destination, tie it on a button, and there. Give him a seat. That’s how people did it. That was normal stuff. We were used to being shuttled around, so it didn’t make too much difference.

CW: But then to come here, it’s so extreme. It’s like another planet.

JW: Yeah. I went to another planet. Interesting planet.

CW: And this was right on the brink of the United States’ involvement in the war.

JW: 1940. They were all busy “negotiating”… like Chamberlain. But we weren’t in. The next year I remember sitting in the living room in this very house, and Grandfather had one of those cathedral-shaped radios with two dry cells behind it to power it, because there was no electricity in the house to power it, and we listened to Roosevelt’s announcement of us entering the war because of Pearl Harbor.

How the news arrived: a cathedral radio of the 1930s.

CW: How old were your grandparents when you came here to live with them?

JW: Grandfather was about sixty-nine. His birthday was seventh of December. To have Roosevelt make that announcement for his birthday was not what he had in mind.

CW: What were your grandparents like?

JW: They were very taciturn people. They rarely spoke. They gave us directions. You come through that door, and you don’t get in the way. Don’t make too much noise. Use the back stairs. Things were settled pretty quickly.

CW: I guess it would have been a pretty big deal for them to suddenly have two children to take care of at that point in their lives.

JW: They simply took it in stride. They just included us in what they were doing. So, [for example] we ate pretty much the way they ate. Grandmother always, without fail, would cook bacon, a half pound at a time. They could knock back a half-pound of bacon without any problem at all. And Grandfather made hotcakes in the morning, the size of a dinner plate, and about three quarters of an inch thick. If you could eat one of those, you were something special. I don’t remember ever getting through one.

CW: He actually cooked them himself?

JW: Oh yeah. He knew how to cook ‘cause he’d been a miner in Alaska. He’d learned a lot of tricks. So he’d stir up this batter. I’d love to know what was in his secret batter. I think they were buckwheat pancakes, but they were heavy-duty, and with a fair amount of fiber in them.

Grandfather talked to me a little…oh, maybe about five minutes in all…about his experiences during the Gold Rush in Alaska. What he relayed was kind of an off-color moment. He went up there on a square rigger, which was the main mode of transport to get up there. They got up there, and tied off the square rigger to the ice, and there was no bathroom on the ship, so to do your business you sat on the rail of the ship, and it was cold enough for everything to freeze solid. He said you had to watch out if you were walking too near the ship. It would be like having a brick land on your head.

He also talked about how they didn’t find any gold, and he built a log cabin with three other men, and by spring they weren’t getting on too well. There were chalk lines on the floor. Step over the line, s-o-b, and you’re dead. He’d go out of the cabin in the morning, and there would be snow stacked on the clothesline.

And that’s all I ever learned about the 1898 Klondike visit.

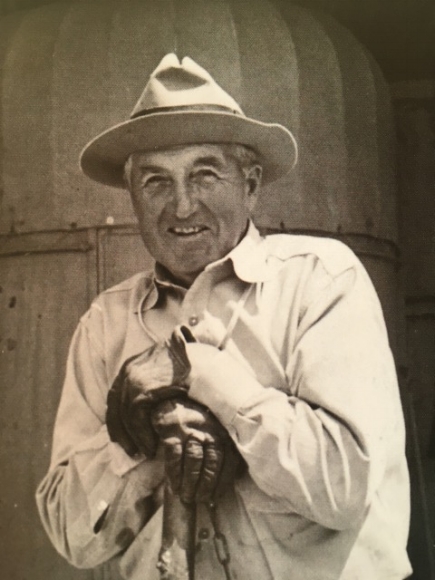

Grandfather...John James Hollister, Sr.

CW: Well, that’s something.

JW: Most of our conversations were like that. I’d get a half a line. It was a quiet house. They were taciturn people...

CW: How did you feel about all this? I can’t help but think that for a little boy it must have been bewildering.

JW: I think I was used to being bewildered. I mean, think how it was. First I got sent out of London to live with the Whartons -- Adeline Hill Wharton-- in Wittenham. That’s in Sussex. I lived in Buckhurst Cottage with them, which always had a good feeling to me. They were better parents than my parents. So we’d already had that experience.

I guess Lynda was there too. It’s funny. I don’t remember Lynda at all in most of these things. She had to have been at the Ranch, but I didn’t see her. She wasn’t part of this sphere that I moved in. Being just a few years older, she went off with her cousins. Good-bye. So she was invisible. And what it was like for her, I don’t know. She’s never spoken of it.

CW: You must have been lonely.

JW: I was used to being lonely. I didn't think about it.

CW: Can you tell me a little about your schooling, and the kind of work you’ve done?

JW: I probably should have taken up the family business, but I thought there were enough shrinks to go around. Clinty in later life decided to employ his M.D. as a license to be a shrink. So there was that, my parents, my sister. All shrinks. That’s enough.

CW: So what did you do?

JW: I got interested in doing other things. I built a lot of houses. Marine construction, a lot of construction. I worked on the ranches here for some years. I got pretty good at tractors of various sizes. But I wasn’t allowed to run the bulldozer until I was sixteen, ‘cause it was valuable and they didn’t want it ruined.

CW: They were worried about the bulldozer, not the kid!

JW: The bulldozer was worth more than the kid.

It sometimes seems like I’ve done a lot of things, but probably things attached to the manual arts. I’ve spent quite a few years with three businesses. I did remodeling of houses, I kept a metal fabrication shop, and I had a tree service.

CW: Where?

JW: Mostly in Marin County. I was on the Ranch here pretty much, as much as I could be, until the age of nineteen. And at nineteen I decided it was time for me to go. It was getting a little bit difficult here.

CW: I wonder how you feel about the Ranch, being here now. Do you love this place? Do you feel an affinity for it?

JW: [pause] I had to make a difficult decision when Mom and Dad died. I could have taken over Parcel One. I’d have had to sell out everything I had, and then some, and gone pretty much into debt to come up with what it would take to buy everyone else out, ‘cause Mom and Dad left it to everybody in sight, and of course everybody wanted their money. Betty [John's wife] and I talked it over at the time and decided it didn’t make that much sense for us. She has a professional license…she’s a shrink too…and she thought making a living out here would be very difficult. So we decided not to do that.

But I did feel the loss of the Ranch quite a lot. I’d like to have been here. If I’d gone in then, it probably would have been all right. But it would have required a major change for us. I can’t quite put the dates together now. We were probably living in Kentfield, in my parents’ old house. A house full of furniture, all this stuff...

So, I don’t know. We decided not to.

I felt a lot of connection to the Ranch, but I also have a lot of trouble with it the way it is now. There’s an awful lot of people running around on my Ranch, just a lot of folks here.

CW: I can understand that. It must be strange for you.

JW: I see that it’s a natural normal land progression in California. If you read history, you see that the ranchos get split up, they get smaller and smaller, and pretty soon there’s houses everywhere you look.

CW: Yes, but here I must interject. This model is a little different, wouldn’t you agree?

JW: It is. But think how many people were here when I remember it. The most formative years for me were during the war. There were a few of the older workers here, and family. All of the houses were right down here in this canyon, except for the bunkhouse at Santa Anita, and the old ranch house at Gaviota, where that big palm tree is.

CW: Oh, do you mean that palm tree that Tony Ochoa planted? Did you know Tony, or his father Louis?

JW: I didn’t know them particularly, but as you come up to make the turn to the office, there’s a big patch of nopales, and they lived there. Louis planted those. He had chickens, and he used to go down to the beach to fish. He was a squatter. Grandfather liked him and said he could stay.

There were two squatters that lived on the Ranch. There was another guy at San Augustine. I never knew his name, but his business was strictly fish. He had a Sea Cab truck. It was a kind of truck that was in style during the 1920s. It had a van body, and he’d fill it up with ice in Santa Barbara, and pack it down with saw dust so it would hold, then fish, put the fish on the ice, and drive back to Santa Barbara to sell the fish.

CW: What years would this have been?

JW: This was probably in the 1920s. He might have been there as late as the early 1930s. He left his truck behind, and eventually “children” stole it. We took it away, but never mind. You don’t want to hear about the truck.

CW: So he had permission to be here.

JW: Yes. Grandfather did that with a lot of people. Fishermen used to come through and they didn’t want to go all the way back to Santa Barbara sometimes, and he often let ‘em hunt on the Ranch, as long as they’d stay up around Coho and they didn’t shoot the deer he wanted to shoot, and they’d bring him fish.

We had abalone steaks that were huge. Abalone used to grow so large…you could find ‘em sixteen inches across! Nobody’s heard of an abalone like this in a long time, but I’ve seen abalone that big. They’ve been fished out.

CW: What other kinds of fish were available in abundance at that time?

JW: All the bottom fish. Sea bass. Three hundred varieties of cod. And on any one of the points, sea grass grew. You know sea grass? It’s a long thin, fibrous element…bright green…that kind of waves in the water? You could go out on any one of those points, run your hands through the sea grass, and find a crab. Big crabs. Just get your hand across one so as not to get pinched and pick it up. Carry it down the beach and roast up a crab.

If you go out at Bulito and go east, the breakwater you come to down there was a good place for spiny lobster. I don’t know if you can still get ‘em down there. The great oil spill in the 1960s, 1964 or whenever it was, killed everything on the coast. Everything. There wasn’t anything left. Killed off all the animals, all the sea grass. Everything gone. From Point Conception to L.A.

CW: When you think about it, don’t you kinda feel like you were here for the best time?

JW: Yes. The experience I had here is not to be replicated. Not in California, not at this time, never. Sure, you can still go out and there's the beach, you can do some things…

And people are interested in surfing. The cowboys of my day would have looked at that… [with disinterest, or disdain?].

CW: Nothing can ever take that away from you. You experienced that wonderful island in time.

JW: But you see, that’s the lens through which I see this place. It’s evolved, and it may be a perfectly natural evolution that’s taking place here, but it’s not my favorite game. There weren’t any rules here in my day. Now you are a land of rules.

CW: I interviewed Lincoln [John’s cousin], and he said something similar. To paraphrase, he said I understand it’s really great, and it could have been way worse, but for me, it feels closed in. You used to just be able to wander, and there was nothing but wildness, and now you inevitably come to a house or a fence or something, and that feels very different. Is that how it is for you?

JW: Yes. It's very different. I used to do things like…I was the game warden. I had a commission signed by Sheriff John Ross, who was famous because he served Santa Barbara County for forty-four years. [He shows me his badge and game warden card, last renewed in 1957.]

CW: What would be your duty in this capacity?

JW: I mostly just validated deer tags, but I was empowered to throw people off the Ranch that shouldn’t be there.

CW: And did you often have to do that?

JW: Yes, quite a few times. I carried a gun.

CW: What kind of people wanted to be here in those days? Hoboes? Hunters? Surfers?

JW: Hoboes weren’t much of a problem. The hoboes left a sign down at the Bulito gate at the tracks, so any hobo stuck there, having gotten off the train and unable to get back on, would know, seeing the sign, that he could go up the canyon and get a meal. Grandmother would almost always feed whoever showed up at the back door. It wasn’t hostile territory. So the hoboes weren’t an issue.

The issue was people who wanted to hunt. Private land has always suffered egregiously from the hunting community. They don’t respect signs. If you annoy them, they set fire to your place.

I had a trick that I rather liked. I used to go down to the beach at night and catch skunks. If you pick up a skunk by the tail it can’t squirt you. Careful, though. They climb up their tail and bite you. So you have a sack handy, put the skunk into the sack, and then when you find somebody’s car that’s not supposed to be there, you put in the sack and close the door. The guy comes along and opens the door, and the skunk by then is pissed.

And you don’t see them again. I imagine I had a certain reputation among some of those people.

CW: Did you see any mountain lions?

JW: Yes, but remember, we lived in a different climate. Mountain lions understood the game as much as anybody else. The game is, if you’re seen and you’re within rifle range, somebody’s gonna shoot at you. So you’d see mountain lions, but they were always out of rifle range. Mountain lions aren’t stupid.

I only recall one close encounter with a mountain lion. I was eating dinner with the Hames family, Eddie and Irene…

[Interviewer’s note: we never did come back to this mountain lion story! Maybe next time...]

...Eddie would have gone off to the war, but Eddie didn’t have any teeth. And being poor, he couldn’t buy them. He ate with his gums. He could eat a green apple with his gums.

CW: Really? Having no teeth would disqualify someone for military service?

JW: No teeth? You can’t go in the army. They wouldn’t have you. They mostly wouldn’t take anyone with false teeth, either. Maybe later in the war, when they were beginning to scratch around for manpower, they’d stretch the rules a bit. But a soldier had to be complete unto himself, and preferably no glasses, no false teeth, no external aids. You have to be able to drop that perfect specimen anywhere in the world with his rifle and tell him to kill.

CW: Were you in the service?

JW: They tried to induct me, but before that I had been in ROTC. I’d wanted to train as an armorer, and that apparently wasn’t possible, or too many people wanted that job, whatever it was. I dropped out of ROTC along with University of Arizona, and they called me for induction. I got all the way through the line, and the measuring machine was last, and the guy said stand up straight there. I stood up straight and left two master sergeants on the ground looking for the parts, because the machine came unraveled. It didn’t measure that high.

CW: How tall are you?

JW: I was then still growing. I grew until I was twenty-five. At my tallest I was about six feet, nine inches. I’ve shrunk down to about six, six. Being tall really does something to you. You get used to seeing the world through a particular angle. Your perception of height and even distance is affected by the angle from which you’re viewing, and now that I’m so much shorter, it throws everything off. But I don’t hit my head on doorways anymore. It’s probably better for my brain.

CW: I guess you get your height from your dad.

JW: My mother was five feet.

CW: That was always amusing about them…the disparity in their heights.

JW: And my first wife was the same. Five feet.

CW: Do you have any children?

JW: Yes, I have a son with whom I am not getting on.

CW: How old is he?

JW: He’s forty-four. He lives in Mexico. He and his wife have a hotel. I haven’t clapped eyes on him in some years now.

CW: Oh, I bet someday he’ll come around. I hope he doesn’t wait too long.

JW: He’ll do what he does. He’s on course to not turn up. And I’m sure that whatever is going on, he’s quite certain that it’s all my fault.

CW: Oh, there are so many things we can’t understand about our own parents until we are looking back on it! It’s an unfortunate thing about the way humans are programmed.

JW: I digress a lot. Sorry.

CW: Oh no, please don’t apologize. I treasure the digressions. But I just keep thinking how odd it must feel for you being here in this house. I would imagine every room evokes memories.

JW: Trying to get the time line right is a little bit hard. When we were first here as kids, I think Dan Pon was here. As you come in through the back door, the first door to the right was his domain. And that was his bathroom. We weren’t allowed to use it.

CW: Was he the Chinese cook?

JW: Yes, and he did other things around the house. He had a hard time with Grandmother. He was always running up against her. And every time he’d lose a battle with Grandmother, he’d reach into the cabinet and get one of those Meissen plates and smash it. “Five dollas!” he’d say and throw it down. He couldn’t get even with Grandmother. She was tough.

CW: What kinds of things did they argue about?

JW: He was sensate. Grandmother was intuitive.

[At about this point we looked at a family photograph on the wall, and John listed the names of everyone, including himself, a blonde-haired baby sitting on his mother’s lap.]

I appear in these photographs, as much as anything, because my parents were, among other things, well off. Dad wasn’t making any money in England to speak of, and Grandmother and Grandfather sent them $150 every month. That was a lot of money in those days. So they were the jet set crowd. Well, there weren’t any jets, so they hopped on a liner. They’d float across to New York, get on a train, and pretty soon they’d be on the West Coast.

CW: When they left their kids behind, don't you think that must have been hard for them?

JW: They couldn’t wait to get rid of us.

CW: Well, maybe that’s part of what made you self-reliant and strong.

JW: It made us what we are, and we are decidedly strange individuals. Yes, probably self-reliant. I’ve always been something of a loner. I like one-to-one relationships. I don’t do that well in a crowd. Put my father in a crowd and he’d run to the middle, get on a chair and wave his arms. He wanted to be seen. Mom would go hide. My inclination would go hide too. You saw me last night. I didn’t get in the middle of anything. I didn’t want any part of it.

CW: I met your dad, late in his life. He was still something of a showman, very charming.

JW: The word is extrovert. He was extroverted. He and I were both the same type in one way, so they always decided I had to be just like him in all ways. He was extroverted, so I must be extroverted. I was always treated as an extrovert. I’m more extroverted than some, quite a lot less than others. He was pretty wild, and his brother George was the same way. They used to do things that would just drive me up the wall. We’d go to a restaurant with the two of them, and the family was quite musical, and they might just start singing. I’d want to crawl under the table.

CW: Speaking of music, someone told me there used to be a piano over there in the living room that your grandmother played. Since we’re here…maybe we should talk about your memories of the house.

JW: Sure. I’ll give you the lay-out. [We begin walking through the house, starting at the fireplace.]

There was a Stickley rocker chair right there. There was a copper coal scuttle, which I still have, right there on the edge of the fireplace. Grandfather put his booted foot on it. About here, there was an overstuffed chair, which was my chair.

There was a couch right here on which grandmother flaked out every night as she was doing her research, reading her books, and nobody talked. There wasn’t any conversation at all. When Grandmother does say something to Grandfather, he says something like, “Now Dot. Now Dot.”

You wonder, do they ever communicate? But I used to hear them at night. Back then I had good hearing. I could hear them through the wall. They would talk long after they were in their bedroom. They conducted the day’s business. They covered everything Grandfather had seen during the day and related it to their forward progress in operating the Ranch. There were technical discussions going on.

They mostly didn’t relate to me at all, which was fine. I liked it all right, actually.

At the back side of the couch was a trestle table. Right over the table there was a fixture sticking down which was the gas jet for the acetylene gas from which the house was run. You could just pull the cord, and it was attached to something that looked like a cigarette lighter. It was a flint with a serrated wheel, and it would make a spark and light the acetylene. So you could turn on the valve, and there was brilliant yellow light. The light was so nice for reading and everything else, when Grandfather first electrified the workers’ houses, he didn’t bother to electrify his own, because he liked the light so much.

CW: What was on the floor?

JW: It was mostly bare floors everywhere. There was a rug near the couch, but mostly bare floors, ‘cause I remember getting splinters in my feet.

CW: So where was that piano?

JW: The piano was here, keyboard perpendicular to the wall, so the curved side of the piano right here, and when you lift the piano lid, goes up…I used to sit on the edge of the bench and listen to Grandmother play Bach. Prelude No 1. It’s still my favorite piece of music. [Click below to hear the lovely Bach prelude that Lottie Hollister used to play on the piano in the old house. Give it a moment or two to start...and then enjoy.]

And so I had that kind of connection with them. But don’t talk. Don’t annoy me. I’m happy to have you here, but don’t be a problem. And by and large, we were not.

CW: And what was your sister doing all this time?

JW: What Lynda was doing, I have no idea. I never saw Lynda.

CW: That’s how it is with siblings sometimes. They have their own separate orbits.

JW: There was a big change made here, probably in the 1960s…[pointing out toward the main porch] made by my cousin Betchen, Uncle Joe’s daughter. Her name is Elizabeth, but she had that German nickname. She was probably born in Germany, because Joe went off to get his PhD at Göttingen just like his mother did. She thought she was an architect, or her design was better than anyone else’s, and she swept in here after Grandfather was out of the house and made some changes. Substantial changes. I could have shot that woman.

CW: Changes...like what?

JW: You could look at the railings on the sleeping porch upstairs and you’ll see what should be here. There wouldn’t be big holes out here. She had a carpenter come in and tear it all out, because she didn’t approve of it. She didn’t like the looks. And there was a big limb coming out of that oak tree in the corner that a quail used to land on, and she had that taken off. She made herself felt. But she was a nurse in charge of the UC terminal ward. She was used to taking charge.

So there used to be a lot more lattice work on which to climb.

The wisteria was always there, although I’m sorry to say the Ranch operators are not horticulturists; they seem to have pruned and pruned with their saw.

CW: Kate Dole said that when she first arrived, the wisteria had grown so much, she had to chop it down to get to the door. You think that might have been the case?

JW: She paid attention to what she was doing. She was a bright girl. She was intuition-thinking, and she used her thinking quite a bit.

[By the way] these psychological categories are just a loose way to get a handle on interaction. I think you’re probably the same as me, more intuitive-feeling.

CW: But we’re doing okay, you and me?

JW: I’m understanding you, and you’re understanding me. I believe we’re probably the same type.

[We walk upstairs]

JW: This was a sleeping porch for the boys. See what the railings are like? It was a real architectural statement. That's what it was like downstairs before Betchen had it changed.

And this was Mom’s room. I still have the whole bedroom set. The bed was here, the chest of drawers there, I think. I don’t know where the commode was. Probably a chair in here. The room went through changes. The old bed I have was her bed when she was young. When she graduated out of the house, they put in a brass bed, because this was used as a guest room.

CW: [In the hallway] Do you remember looking out this window and seeing the pool?

JW: The pool. It used to be full of water. That was the deep end, and that was the shallow end. I dove into the shallow end once, broke my nose, and didn’t understand that you’re supposed to do something about it, so it’s been a little off ever since.

Right here in this hallway was a secretary. Why I couldn’t tell you. Glass-fronted bookshelves. Never used that I can tell, but it was Grandmother’s furniture. She liked it.

This was a sometime guest room also.

This is Grandfather and Grandmother’s room, and outside of that wall is my bedroom. I somehow remembered this as a larger room than it seems now. The bed was here, chest of drawers…I don’t think I ever saw a fire in the fireplace. I’m sure it worked, but if they built fires I wasn’t aware of it.

One of the main features of this was there was a string coming down from up there, a wire strung through the trees with a big handle on it down here, and when Grandfather went to bed he went out and got ahold of that and pulled it. It was the switch on the generator. And all the lights went out. The generator was propelled by a gasoline engine. He went to bed, and it was time for everybody to go to bed. That was the end of the lights.

Sometimes he’d take his single shot four-ten shotgun out on the deck, and he hated rabbits. The rabbits would come eat his lawn and he didn’t want any of that, bang, that’d be the end of another rabbit, and by the morning, some fox or somebody would have taken it away. So there weren’t any corpus delicti left on the lawn.

CW: [as we enter John's room] So this was your room? Is it true you used to climb out of the window at night?

The window into the night...and freedom.

JW: Oh, yeah. I’ll show you. I can’t do it anymore. I’d step onto those beam ends, crawl down the lattice work, and I was off after they’d gone to bed.

Here’s where my bed was. Whenever I had pets, I kept them in the closet. I’m sure Grandmother knew and didn’t approve much. She didn’t say anything.

[Back to the window] So I’d put this window up and climb out, step around to those beam ends, and lower myself down between the beams ‘til my foot caught on the front work. I’d just climb down, and I was off to the races, having a fine time for myself. Whoopee!

CW: But where did you go? What is there to do?

JW: I’m kind of a night owl. I’d go down to the orchard, pick fruit and eat it.

CW: Oh, that’s so touching.

JW: I’d walk down to the beach, just wander around the canyon.

CW: How old are you in this scenario?

JW: By the time I was busy doing my nighttime excursions, I was probably twelve, maybe thirteen.

CW: You never felt scared?

JW: No. Later on, I got afraid of the dark, but not then. I never even thought about it.

CW: So here you would be, just you and the night. Did you have a sense of wonder about it?

JW: Children don’t specifically have a sense of wonder. I don’t think that’s true of children. Children accept as normal what they see. They hope that what they see as normal remains, it doesn’t change. Where there’s change, it upsets children often.

So I kind of took a fix on the world then.

[Coming upon a map displaying the Hollister Ranch and its parcels.] Look at them all, a hundred and forty of them. I used to go up there, there wasn’t anyone up there except cows.

CW: Oh. I guess it's really weird for you. But I keep coming back to the fact that it's so much better than it might have been. Some of the alternative scenarios were quite disturbing.

JW: I know. I’m not arguing with you. There could have been ticky tacky boxes six feet away from each other all the way up the coast. The developers would have loved it.

That’s the same reason you don't want everybody on the beaches, because as soon as they have easy access, it will be wall-to-wall trash extending up into the middle kingdom. It just doesn’t work.

[Looking into a bathroom] They were built fabulously. Solid brass fixtures. No showers. Nobody had the concept of a shower. They weren’t interested. If you wanted a shower, you’d go out and stand in the rain.

One of the features of this house, I don’t know if it’s still there or not, when Walter Bliss designed the house, he put a 300-gallon water tank in the attic, and there’s a sheet metal collection area on the roof so that 300 gallons of rain water were in that tank, un-mineralized soft water, which Grandmother washed her hair with. There was a spigot on the deck and she’d draw water. I think I was the only child to ever see her with her hair down, and her hair reached all the way to the floor. She let it down, washed her hair, and put it up in a bun. at the back of her head. I don’t think anyone but Grandfather and myself ever saw her with her hair down.

Grandmother...Dorothy Lottie (Dot) Steffens Hollister

CW: Oh, that's a lovely image.

JW: Here’s the little bathroom. I had many unhappy days in the bathroom, because they made me take baths.

There was a fixture coming out with a gas jet and we had acetylene light. It worked like a charm. The acetylene generator was out there about halfway to the bridge, far enough that if it blew up it wouldn’t take the house with it.

[Continuing our walk] Whatever they didn’t need went in the attic. Cathedral radios...at one time there were two or three cathedral radios up there. There was a wind-up Victrola, with records printed on only one side, I used to go up to the attic and play them. I still have a bunch of 78 rpm records.

[Running his hands on a strip of wood where the walls meet, by the stairs.] I always liked this feature, one of the most elegant features of a plaster house, to put wood guards on the corners where people’s hands and fingers were apt to touch.

Detail of wooden guard

[Downstairs again] This closet here was always full of Grandpa’s guns.

[Pointing to another door] That goes down to the basement . There was a coal furnace in the basement. Coal was the one fuel medium that you could get delivered.

The pantry of course is where all the Meissen porcelain was kept. I have what remains. Between Dan and my father, they managed to break practically all of it. The pattern was Onion, although they also had Rosebud. Grandmother first saw it when she was at Göttingen, and not to run short, she came home with maybe a dozen barrels, full-size wooden barrels stuffed with excelsior…remember what excelsior is? It’s fine slivers of wood, very springy, used for furniture stuffing or packing material. It was excellent packing material. They put all the plates down in that, and the stevedores could handle those kegs of plates without breaking any.

This was Dan’s room. The bed was on that wall, and the entire room was papered with Chinese newspapers. He came in here, and this was his Middle Kingdom.

CW: Do you remember the sound track at night out here? The coyote songs, the frogs…

JW: There weren’t a lot of coyotes. I used to see a lot more coyotes at Las Cruces than anywhere else. I can remember hearing them singing up there, crawl through the grass, sneak up on ‘em and surprise ‘em. Oh, they’d get so embarrassed. They’d slink off through the brush. They didn’t want anybody to be watching. If you think there’s a coyote on a brushy hillside, just sit there and stare at it. He’ll turn his head or do something else…he can’t stand to be looked at. Most animals are like that.

CW: Did you ever have an interesting encounter with a wild animal?

JW: No. We were…if we had been today the kids we were then, we would all be in the crossbar hotel looking out. We tended to shoot practically everything. It was a different time. And in case you ever wondered, raccoons are excellent eating. They may look cute and cuddly, and they’re really fun as pets when they’re about this big. When they get bigger, they bite.

CW: Did you ever have to shoot dinner?

JW: No...Mom used to be told by her father to go out and shoot dinner. She’d be given half a dozen bullets for the twenty-two. But even in later life, she didn’t entirely give up guns. Like everybody in the family, she didn’t like blue jays. Blue jays are famous for eating the eggs and the young of other birds. So she kept a twenty-two in the front room loaded with bird shot, and when she’d see the blue jay she’d come running out and blaze away at ‘em.

[We’re in the kitchen again] Oh, right here was Grandfather’s stove. It was a little four-burner stove, sitting right here. He had a soapstone griddle. They’re still made. They're wonderful, with very even heat distribution. If you wanna cook something like a flapjack that’s this big, that’s what you use.

There was a wooden table right here. That was the table Grandfather and Grandmother always sat at. There were two bins that you could pull out that had flour in them, a common enough thing of the day. A Roper gas stove right here with the warming oven over the top. And here we had an interesting thing. We had a water boiler. But it was something called a side arm water boiler. Just a big tank. It didn’t have anything in it except water. And alongside it was a cylinder about that high, down closer to the floor, with a big copper coil in it and a gas jet at the bottom, so you’d light up the acetylene gas and the big flame would come up through this coil and it would heat the water by something called thermo-cycling. You can look that up. Hot water rises, cold water falls. So it automatically exchanges the water in the tank until the whole tank is hot. Modern water heaters work the same way, I think.

This was a pantry area. What baking Grandmother did was done in here. And occasionally she made me “healthy” cookies out of Adele Davis. She was doing Adele Davis before anybody had heard of her. There was a refrigerator right here.

That [pointing outside] was a walk-in cooler with an engine-driven compressor. We used to hang our deer in there. We’d put the whole deer in there, hide, horns, and all, hanging on a hooks. You’d leave ‘em in there until they’d turn green, and get ahold of the hide and pull the hide right off with a sharp knife and cut off all that rotten stuff, and what was left would melt in your mouth. You could cut it with a fork.

The mock orange was planted by Grandmother, and that’s still there. But many of the things have gone away, and I see a tremendous amount of volunteer oaks. This place is much more hemmed in than it once was. The bees were up there above the road. There were about ten hives. Grandfather tended them. We had the centrifugal extractor for getting the honey out of the cone.

Looking towards the house from behind the walk-in cooler; the mock orange planted by Lottie Hollister is still growing.

CW: Seems like you guys were pretty self-sufficient.

JW: The orchard had twenty-two varieties of fruit and nuts in it. Ten acres of lemons, and ten acres of oranges. There were five or six walnut trees. Grandfather put up a big gunny sack filled with walnuts and sent them north up to Mom every year, and a five-gallon tin of honey.

[Turning back to the interior] All the crockery would have been up here. Dan would get one of those plates. He’d be so angry! He and Grandmother made each other crazy. She was the mistress of the house and he was just barely having any of that. But he liked children, and he took great care of my sister and me. He used to make us Junket. With colors. Blue or pink were the colors we usually got.

[Dining room] There was a big table here, a sideboard there.

CW: Did the family gather in this room to eat? Did you eat together?

JW: They mostly didn’t get along that well. We’d come together Christmas. I remember some grand Christmases. I think the last one I was maybe eight, and Uncle Joe looked at me...and he saw me, all right. He gave me a present, which I unwrapped in a hurry. It was a hand axe. My parents said, “Oh, I don’t know about that.” Joe said, “Leave him alone. He’ll have some fun.” I walked all the way over to Las Ovejas with that hand axe and chopped down a whole bunch of willow trees.

CW: When you said Uncle Joe “saw” you…what does that mean? Like he understood you, sort of recognized where you were at?

JW: Yes. He wanted me to be a geologist. He was the first person who got Charlie and Lenny [Lincoln] into geology.

It was the Wild West. Wild lands. Any number of bad things could happen to you out here. You could be confronted by an angry cow and be gored and killed. I learned how to read cattle long ago. I don’t have any trouble with them, but for somebody coming on the ranch not knowing them or what to do with them, potentially a lot of bad things could have happened. But mostly didn’t.

CW: How do you think this experience has shaped your world view? Was this the formative place for you?

JW: Well, of course it was formative. But it’s hard to see exactly how.

CW: Because it’s all you knew?

JW: As I said before, the operating mode of child is whatever is presented as status quo is what’s normal. It doesn’t matter if it’s permissive, abusive…whatever it is…it’s normal. You may object to it or run away from it or do whatever you do, but it’s not an exceptional circumstance.

I mean, I saw that the childhood I had with my parents was very different than the experiences of my peers. They had an entirely different situation. I just thought well, this is my family. I didn’t ask, “Mum, why are you like this instead of like that?” It didn’t occur to me to say it.

CW: What advice would you give to a younger person based on what life has taught you?

JW: You think I’d have learned something in eighty-two years. But I haven’t any idea what it is exactly. It’s such a different world now. If you’re not computer literate, you’re out in the dark. I don’t feel in the dark, but when I talk to anybody who is doing this all day [staring into a screen] I think, “What is that all about? What’s it about?”

CW: It happened so fast. Computer technology took over.

JW: I just wonder, what’s in that little box that’s so interesting? Why not look out? Look around. I always look out and look around. I look through the window. I want to see what’s going on. What birds or animals are coming and going? Or people and their antics. I’m a very visual person. Men are said to be visual anyway but I think I have that more than most.

CW: You seem like an insightful person who is quietly observing.

JW: I also about half-trained my way to being a shrink. My folks trained me. That used to be the way to do it.

John's Parents: Joe Wheelwright and Jane Hollister Wheelwright

CW: Well, I think you're one of the coolest of all the Hollisters.

JW: I’m almost un-Hollister. In the actual family, there are so few intuitives that people mostly don’t know what to make of intuitives. Clinty was an intuitive. Grandmother. But among the men, they’re all sensate.

CW: Maybe because not everyone will know these terms…and I only vaguely do…maybe you can tell me what they mean, in the most succinct way. Intuitive versus sensate.

JW: My parents taught me psychological typing. Intuitive adds two and three and gets four, and it’s the right answer. Sensate people collect facts. They’re very good with facts. Sensate, goes into a room, and without effort, they’ll be able to tell you who was there and what they were wearing. Just like that, no effort involved. Most sensate people know what time it is. I wear a wristwatch because I have very little time sense. I put the eggs on to cook, and I’m lucky to get back to them before they get burned. When an intuitive walks into a room, they get the sense of people. They sense the other stuff that the sensate people weren’t so focused on, the undercurrents, the side glances, the body language.

Then of course, "thinking" explains itself. The first thing you do when you wake up, your first jump out of the box, the function that operates the best is generally what you are. People who are primarily thinking, as my wife is, her head is going like a slot machine. Wheels and dials whirring. I wake up, first thing I do is look out the window. Are there clouds? Wind? Is anything flying by?

CW: It seems that having such crucial years in this house and this place would have tended to make you that way.

JW: I needed to be an observant person to live in anything approaching a frontier situation. You pretty much have to see everything.

CW: What do you feel proud of? What do you feel good about?

JW: I don’t know. More than being proud, what I tend to see are the missed opportunities. I see things that I might have done and didn’t.

CW: And you regret them now?

JW: Yeah. I should have gotten an art degree instead of going down the path that I went. I was headed down a liberal arts program and then signed off on it. I got mononucleosis and I bombed out of college after about two years. I should have graduated class of '56. Subsequently as I got more interested in construction and related subjects I began to train as an architect in San Francisco. I didn’t stick that one out either but I got enough tools of the trade to start designing houses.

I did more of what was common in the 19th century. People would go to school so they’d know enough to get a handle on something, and that was enough of school. I always speak of Grandfather as having a degree from MIT. He went to MIT but he only stayed long enough to get the necessary tools to do the job he wanted to do. George Hurst owned the silver mines in Mexico and hired Grandfather to be the superintendent, so Grandfather needed to know enough engineering to take that on. He had already graduated from Stanford in geology, so this was just sorta like post-grad stuff. He didn’t need a degree. What are you gonna do with a degree? Put it on the wall?

CW: I see you as a person who was essentially dropped in between two eras. You were in a transitional period.

JW: Yes. A transitional period. So I was in this middle ground. The world changed and I didn’t. I’ve remained kind of a late 19th century person all this time. I don’t quite fit in.

I was a person who thought, ”Well, be a deputy sheriff, put on your gun, and do your stuff.” But that wasn’t the way the world would work.

CW: So what would have been different had you realized the need for a degree?

JW: I would have gotten a degree in art.

CW: And you think maybe that would have been more fulfilling?

JW: I don’t think it would have made me a better artist. I think it would have given me better recognition. The world operates on, “Oh, and what degree do you have?” If you don’t have a degree, you aren’t anybody.

CW: What kind of art do you do?

JW: I used to do mostly sculpture. Steel sculpture. I like steel. I consider steel a plastic material.

CW: You don’t do that anymore?

JW: Once in a while I make something. I’m kind of planning on building a big piece of sculpture. It’ll be too heavy to move when I get done with it.

CW: Where would a person go to see your work?

JW: You’d have to go to my house, probably. And I keep telling people, “You like it? Take it away.” I also paint. Watercolor. I tried oil and acrylic. They’re not immediate enough for me. I prefer something that goes quick, dries, fold it up, and go on and do whatever else you were doing.

CW: So you would paint landscapes?

JW: Mostly landscape. I used to do sketches of the Ranch the way it looked before anybody was there.

CW: Do you still have any of those?

JW: A couple.

CW: Someday I’d love to see them. Maybe next time I’m in Point Reyes.

JW: We’ll be there for a little while longer. If it gets any more crowded in Pt. Reyes, I’m gonna talk my wife into moving to Oregon. She was born in Bend, so she shouldn’t mind going back there. Point Reyes was a nice little one-horse town once upon a time, but it’s expensive and has way too many people in it now. It’s been found.

CW: We’ve talked about how the Ranch has changed. How has it remained constant? Is there anything here that feels like a touchstone? Something about it that hasn’t changed?

JW: It’s all gone. But it was wonderful. You’d have to interview me for a hundred hours if you want to get it all. I don't know if you've got that much patience.

I remember I saw the first fall harvest in 1940. They had a stationary bailer. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen one. You could probably find on in historical records. Just a giant thing with a great long arm. Compress the hay to make bales. Powered by a tractor nearby. All tractors had power take off, with a flat wheel sticking off the transmission, you take a great long leather belt, lay it over the wheel, and over the bailer, use the engine on the tractor to power the bailer. And there’s cowboys galore running this thing. Guys with pitchforks throwing hay into the bailer. The hay has already been mowed and raked, but they have to gather it. To gather it, they have a fairly simple contrivance. A pair of horses, a wheel on each side, and forks that ride along about that far above the ground. So you drive the horses around picking up hay until you get such a big pile you can’t see over it, then you guide ‘em over to the bailer. Have the horses back up, the load of hay stays there, and the guy throwing it into the bailer. so this is a labor-intensive operation. So I got to see that. I can still see the whole thing in my mind. It was a fabulous view. I’ve never forgotten it.

CW: What an introduction! You’ve experienced aspects of this ranch that no one will ever know again.

JW: But starting this way, with this kind of experience in the California West…I never wanted to leave it. But I could see by the time I was nineteen that I was being shaped by all this, and I could see, among other things, that the ranches were gonna get sold. One way or the other. I was gonna be out of a place. I tried to get a canyon with the shares that I had, but they wouldn’t do that.

CW: So did you decide you would leave of your own volition before you were exiled? Was it something like that?

JW: Yeah. I didn’t wanna get the boot. I thought I’d leave before that happened…

CW: So you saw that you had been shaped for a way of life that was not going to continue.

JW: An agrarian life. It wouldn’t have necessarily been a bad life, but starting as I had, and with the prospects that I had, the likelihood that I would have been able to collect enough money to buy anything even like the Flint Ranch, would be pretty dim. (That was the name of the thousand-acre piece that Grandfather picked up to connect Agua Caliente with Las Cruces.) So it would have been very hard to follow that agrarian life.

Everybody that worked on the Ranch were sensation-feeling. Except Jack. who was sensation- thinking, but all the rest of them were sensation-feeling. Sensation is detail, detail, detail, detail. They could do details until it runs out your ears, and every time they just want to do it better than the time before. That’s how sensation works. And it’s perfect for a ranch, because it’s all about details. It’s about getting all the details right, and doing it day after day, and never missing. And feeling. What feeling does…feelers all get along with each other. So here you have fifteen, sixteen men and they all have to get along. No fist fights. You don’t want any of that. It’s disruptive. So they were all the same type. Grandmother was probably responsible for a lot of that, because she had a degree in psychology. She knew all about Carl Jung. She had all the collected works in the original German, which is the way she would read.

More digressions...and I can't remember what I was leading to.

CW: I think I’m going to have to do another installment of this interview. We can’t do it all justice now.

JW: If you’re gonna interview me again, don’t wait too long. The doctors would like me to take more medications than I do, but I’m against it. Don’t look for me to last way up into my nineties.

I don’t have great desire to live forever. Nobody lives forever, and if you look at most ordinary persons’ lives, there isn’t a whole lot of life past eighty-five. Eighty-five is a tipping point. After that, it’s a ski jump going down.

Mom had a pretty good rising life to ninety-three. Then she had a life-threatening experience. She almost died. Dad kinda saw her through. They spent every day in ICU for a long time, but she was never the same afterwards. So much of her had gone away after that. And Dad just lasted to ninety-four. He had bladder cancer. He just wasn’t having a good time, and it had advanced to the point where they wanted to do major surgery on him, and he didn’t want the surgery. He wanted to die, and Mom made him promise that he wouldn’t overtly take his life. So they were living in that cottage near Doyle in Montecito. He felt a heart attack coming on. So he sent Mom out to do some things, to keep her busy for about twenty minutes while he died.

CW: I respect that. There’s a kind of dignity and courage in that…don’t you agree?

JW: It was the right thing.

CW: He was in command.

JW: If he’d had surgery…he had grandmothers who lived to be a hundred…he probably could have lived longer. But what’s the point? There comes a point where so much of life has slipped under the bridge, you’re left with memories and not a future.

CW: And you become increasingly dependent on others, and everything on you hurts. Even five years ago, I’m not sure I would have understood this, but having watched my mother at the end of her life, I do. And I finally know I’m mortal too.

JW: We’re all mortal, and to a certain extent, we’re subject to happenstance.

As an aside, I usually get my exercise riding a bicycle, and they closed the path I used to ride on. It was level. I liked it. The only one available is uphill. So I’ve been pushing myself up this grade. I push until I run out of wind and I have to stop. Then I go a little more. I have atrial fibrillation…do you know what that is?

CW: Not exactly.

JW: It’s one of the chambers of the heart begins to fibrillate…flutter. And it doesn’t pump blood very well when it’s doing that. So I’ve had that since I was forty. Since I’ve been pushing myself up that grade, I haven’t had an attack of it. So maybe I’m extending my life in some way. We’ll see. So I’ll do that. That’s all right.

But if you have other questions, there’s the telephone.

CW: Before we wrap up, I have a couple of questions I like to ask, and also, I'd like to take a couple of pictures.

JW: I should have shaved.

CW: No, you look exactly as you should.

JW: Gnarly.

CW: So...what do think is a good life?

JW: I think you should make an effort not to trample on anybody. Try to conduct yourself in a way that doesn’t make too much trouble for other people. That’s what this place does to you. That's what this place is like.

CW: You mean the Ranch?

JW: Yes. These are things instilled early on.

CW: How would you like to be remembered?

JW: As the gun slinger who used to shoot up Santa Barbara? Maybe not. I don’t know if the statute of limitations ends. How do I want to be remembered? These seem like perfectly reasonable questions, but I don’t know how to answer them.

CW: Don’t worry. They’re not that reasonable. If somebody asked me that, I wouldn’t have a clue.

But here’s one more. What gives you hope? Because it’s so easy to feel depressed!

JW: It is easy to feel depressed. I have less depression when I’m in the wild.

I used to get very lonely out on the ranch, because there really wasn’t anybody my age to talk to. Many relationships really weren’t very satisfactory.

CW: What makes you feel better? What gives you comfort?

JW: I spend a lot of time dreaming about the things I used to enjoy doing. And I think sometimes that I’d like to do one of them again.

My wife is going to get in my way, but I would like to get a pilot’s license, and Id like to get an ultra-light, and I’d like to go flying. I don’t want to go anywhere in particular, I just want to go with the birds. Go up and talk to my ravens.

John Hollister Wheelwright with His Wife Betty Coon Wheelwright

And I’d like very much to buy a small sailboat and sail to Hawaii or maybe Japan. It’s only 7,000 miles across. Why not?

CW: But not by yourself….right? Would Betty go with you?

JW: No. I would do it by myself. But she would be against it. She doesn’t want to lose me.

CW: Well, that’s the other side of being loved.

And you still do find peace and hope in communing with nature…the wild...yes? That’s still there.

JW: And I used to love the hunting. I don’t know where to replicate that. There’s hunt clubs in the south; I don’t know if I’d want to go that far just for the opportunity to kill something. But it’s not about killing something. When I had those wonderful days on the Ranch, the best times I ever had hunting, Grandfather used to lend me his single shot four-ten, a little tiny shotgun, and I’d go to maybe Santa Anita slough and wait for the ducks to come in. You’re there amidst the most beautiful possible landscape, sitting in the rushes...I’d be there early in the morning or late at night, as the light’s changing…this is special.

CW: The total experience.

JW: And maybe you get to eat a duck too, which is always welcome. But those are things I think about doing. Do I have enough time or energy left to do it? I don’t know.

CW: You've had some of those experiences, and nothing can ever take that away from you.

JW: If I could buy a Piper Cub, which is about the largest airplane I could qualify for with a sport license…I couldn’t get a regular pilot’s license because of my eyesight….I would think about flying it to Brooklyn, Maine and go see my sister. It’s only 4,000 miles. Why not?

CW: I like that. Why not? That’s my favorite philosophy.

JW: I’d probably have to put it down every hundred or hundred and fifty miles, because it doesn’t hold much gas.

CW: Intermittent stops…that could be interesting...who knows what you’d see along the way?