A great-grandson of rancher, entrepreneur and philanthropist William Welles Hollister, Doyle Hollister has a profound connection to the ranch that bears his family name. In the following interview he talks about his childhood days in this wild and magical place, about loss and searching, and finding his way back. This conversation took place on November 7, 2015 at his Hollister Ranch home, high on a windswept ridge above canyons and sea and the Western Gate.

I Only Went Out For A Walk

DH: I am Clinton Doyle Hollister and I was born in Cottage Hospital July 4, 1949. My father was Clinton, and my son is also named Clinton…Clinton Kyle. I also have a daughter, Rebecca Ashley, named after my mother, Rebecca Doyle. I go by Doyle.

CW: We might as well cut to the chase. I don’t feel that I can talk to you without talking about this place, which is such a huge part of what shaped who you are.

DH: First of all, this is Joe and Jane’s house, and there is a mythology, a vague mythology, of how they picked this. Supposedly, Jane’s daughter Linda picked it out when Jane said go find me a parcel after the Ranch was sold. No one really knows why this one, but the thought was that it was a box canyon and no houses would be visible. Or, maybe it was just parcel # 1, doubt that but…they offered parcels to the family for a reduced price… it was only $50,000 to our family to buy a hundred acres. So Jane did. My father chose not to do it, because he was…well, that’s a long story about how much pain he was in because the Ranch sold.

Anyway, Jane and Joe bought this property, and they were dividing their time between here and Kentfield up north. They had to build a house. I think they finished it in 1975. I think they bought it in 1970 or something like that. It was quite a project. It was not easy to build this house, in terms of where it is, all sandstone rock. Once the house was built, they would spend six months up in Kentfield…they were both doing analysis at the Jung Institute in San Francisco, they started that…and come here for six months. Probably around 1983 or 1984, they moved out here and stayed here completely. They lived here until roughly 1998, when they were about 94 years old.

Growing up here as children, when the family owned the Ranch, we lived in different houses in the Bulito Canyon. We lived in Saunders’ Knoll for a while, we lived in what was the foreman’s house sometimes, which is the bigger house pretty close to the main house. We never lived in the big house that my grandfather built because the Doles were in there, for the most part…and it was too big! It’s just huge. Ten bedrooms or whatever. And we lived in what’s called The Ritz, which is LaRue’s old house up there, and then there’s a little house below that, just east of the Ritz, which my uncle, Joe Hollister, the geologist, built, and we lived there for a while too. So we lived in different places.

But we were all a hunting culture up here, and every once in a while we’d have this inclination to go where it was most wild on the ranch. We did a lot of hunting all over the ranch, but when we really got industrious, we would get up very early in the morning, get in our little Willy’s jeeps, completely dark, usually fog just socked into this ridge, and we’d drive just this holy nightmare of a road, the road we just came down on, De la Cresta, to get to this property here to do some hunting in this area, because the deer up here are a combination of mule deer and black tail. They call them Pacificos, and they’re much bigger deer, wild-looking things, so we would come back up here to see if we could snag one of those.

CW: So deer was your prey, mostly?

DH: Yeah, deer hunting...pigs...dove…quail...We had a club house at the Ritz. My family and other families…

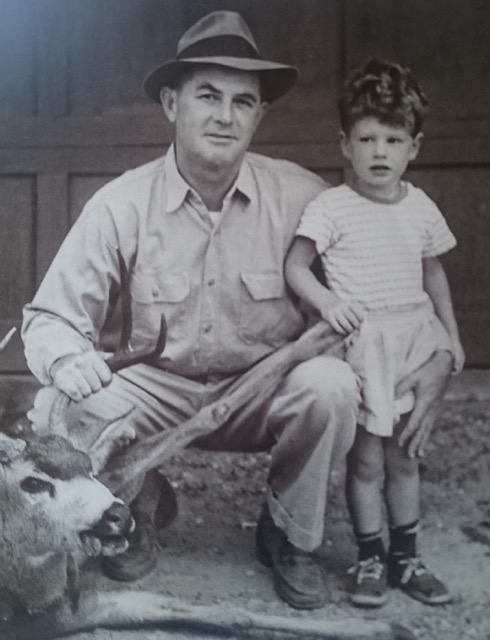

Clint and Doyle

CW: When you say “we”, who is included?

DH: The Ranch was originally owned by seven families, but the only family that really inhabited the Ranch on a regular basis was my family of origin, which was my father Clinton, my mom Rebecca, and my brother David and myself. David is my younger brother. He lives up in Arroyo Grande. Charlie and Lincoln, my half brothers from my father’s first marriage, were here, certainly before we were born, more often. They were part of the ranch family earlier on, so as younger boys they were here. But, when we, my brother David and myself, were coming out as young boys, they were already doing their schooling. Boarding school…Lincoln went to Thatcher, then Harvard. Charlie went to some day school down south and eventually off to, I think it was Columbia. So they were moving out into their education. They both ended up becoming geologists. Charlie was an oceanographer, and Lincoln was a crystallographer…he’s quite famous. Charlie was too, but as Lincoln says, he wasn’t a good scientist. (laughter) Just a little sibling rivalry there.

Anyway, to me the most wild and magical places on the Ranch are your canyon, Sacate, and here in the Cojo. Both canyons have a spiritual energy that is easily felt. As a boy, having no filter, interacting with the wilderness, I always registered a different feeling here, and a different feeling at the head of Sacate.

CW: So you sensed that, even as a kid?

DH: Oh yeah. There is definitely a place my mind would drift into, a different consciousness and I would be stimulated by the energy of the land. It makes perfect sense to me that the Chumash thought of this canyon as the Western Gate. Plus it’s a place of boundaries. This is what’s interesting about this property here in the Cojo, the collision of different geological entities…you have the marine terrain there and then you have the inland terrain here. Sometimes I’ll have fog coming this way, and fog coming that way, and they’ll meet right here, and do this dance, this swirl of symmetry up here. It’s the mainland and the marine land colliding.

And of course right there you have the coastline that goes east-west and then right at Point Conception it goes north-south. The whole California coast changes right there. So that’s a boundary that causes tumultuous weather up here. We get some incredible, radical weather shifting that I find very…fun. (laughter) Some people don’t like it, but I love it. I’ve been here sitting in the house with rain coming down and looking out there and it’s sunny on the ocean, and I’ve had the reverse, where I’m in complete sun and it’s raining over the ocean. So all sorts of interesting weather patterns happen up here due to boundary collisions.

CW: I like that idea of boundary collisions. It feels like a metaphor for something else too.

DH: I’ve always been transfixed with boundaries because I’m a therapist and I do mostly interpersonal work and it’s about boundaries between people. It’s powerful. That’s where the collisions are, that’s where the harmony happens, the disconnect, the connect…at the boundaries. Boundaries between people and between physical and geographic entities are really fascinating to me.

CW: So it’s no coincidence that you went into the field you’re in? It feels like a natural fit.

DH: It wasn’t what I was going to be. I got a master’s in English. I was going to be an English teacher like Bob Isaacson. I actually crossed over with Bob at UCSB. He was just moving out of his Master’s Degree and I was moving into the program.

CW: Is that how you met Bob?

DH: No, I knew Bob earlier too. He was at Thatcher and I was at Midland for high school. He was two years ahead of me. But I knew him originally from then because we both played on the soccer team, he was left fullback, and I was right wing, so we were at each other constantly on the soccer field. The two ranch boys colliding in battle. Bob’s calves were ridiculously huge, as big as my thighs, but I was faster than him and he hated that. We had a lot of fun.

So I was going to be an English teacher, but I got all messed up. I got divorced at 25, married too young. I went into therapy to figure myself out. I thought, “Now, this is interesting. This therapy thing is pretty cool. I could do this.” I thought I could actually be a better therapist than the therapist I was seeing. So I talked to Joe and Jane and my cousin from my mother’s side, Anne Chalfant, who was a social worker at Berkeley. I went from one master’s degree in English right into another in counseling psych. So all that time between 1965 and 1980, when I came back to set up my practice…I’d been in boarding school, undergraduate college, or in different graduate programs, except for one year living in Italy after graduating from Cal.

CW: And you said you have two kids?

DH: Yes. My daughter Rebecca Ashley is a social worker, currently in Rwanda, and has done a lot of work in Africa. Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania. She’s 28. My oldest is Kyle, and he’s 30. He is a wizard film editor, the next James Cameron, one of his mentors. They’re both great kids, doing good things.

CW: Getting back to the Ranch, do you have any specific memories of your early days here that you’d like to share?

DH: You know the Native American notion of power spots…there has to be a story to a place for it to be a power spot. I can’t go anywhere on this Ranch without having reflections of some story. Nobody can believe I wasn’t a surfer, but I really wasn’t. I’d go to the beach often--we would ride horses on the beach--but there was only one summer that I went surfing.

Most of the time I was in the backcountry. I was always in the mountains. We did a lot of driving around in jeeps, walking up and down canyons…but my favorite was just to be completely alone in the backcountry. I didn’t really like hunting with other people. I liked being absolutely on my own, walking down a canyon, or up canyon, usually hunting. I can’t go anywhere on the ranch without having some sort of memory attached to where I am. I remember when I hunted this area or that area…maybe I got a deer, maybe I didn’t…but those moments and places all have a story to them. There were many, many magical moments as well where there was this altered state that would happen.

CW: Did you feel that sense of merging?

DH: Absolutely. That’s the merging that Jane was talking about, that the paper I wrote was about. The merging experience happened to me often but as a kid I didn’t know it was going on. I just knew there was something really peaceful or exhilarating, just this experience that was special. So I would just notice it. I would have these moments of interplay between animal Doyle and animal out there. This super-alert consciousness, high level intuitive awareness going on. Just magical moments.

I had these moments a lot up here. I didn’t really know what they were. Then, I started reading Jane’s stuff decades later, and I thought, there it is… that’s what it is. It’s merging. It’s the inner soul and outer soul resonating, or the inner psychic nature and the outer physical nature vibrating together.

CW: Can you learn to invite it? Can you make it happen?

DH: Yeah, but it doesn’t happen when you’re in some interpersonal context. You have to be alone. There’s a whole process that occurs. As a kid, eight, nine, ten years old, I’d be walking down these canyons, by myself with a thirty-thirty Winchester rifle in my hands, all alone. When you first are left alone in the wild, it’s a bit daunting. It’s scary to be a little boy so alone. The world is so big, and there are a lot of things that could happen to you. Though, quite amazingly, nothing ever did.

CW: But you felt some anxiety.

DH: I would feel some anxiety initially. There was this initial phase of anxiously pushing it too hard, ego assertion or something fear based, and then all of a sudden I would just drift into this place where the fear and aggression would slip away and this interplay with whatever was going on around me outside and whatever was going on inside me were all lined up.

CW: Did it change you? Do you feel stronger afterwards?

DH: Well, I’m currently rewriting a memoir of sorts. I have many stories, as you might imagine. The first section is different stories about special moments that I had on the ranch as a kid. As I look at the stories, they’re really stories of initiation. In some ways, these wilderness experiences were a way of self-initiation. Something really happened to me, some character fortification of some sort. Essentially, this land initiated me, though I didn’t know it at the time.

Also, I was just thinking about this yesterday, and Jane talks about this too, the interplay of her Self with nature really sunk her into her instincts. She had a really solid, well-developed instinctual life, both psychologically and also via her interplay with nature. I feel the same thing, that my trust in my instincts and my awareness of my instincts really grew out of these early childhood merging experiences.

Here come the ravens. Look! Here they come. You’re gonna get the dance.

(Ravens in Flight by Atli Harðarson)

CW: Jane and Joe?

DH: Jane and Joe. Right there. They came to visit. They’re amazing creatures. Sometimes they fold their wings up, turn upside down and just drop like lead rocks for about ten or fifteen feet, then come out of it, and open up their wings. They’re just having so much fun!

CW: I don’t think I’ll ever forget this moment, just being here. The ravens, all of it. And the islands are so clear…is that Santa Rosa?

DH: That’s Santa Rosa. And that’s San Miguel, right there. San Miguel. I love the curvatures…and the colors change…I have hundreds of photographs of San Miguel.

CW: I could take dozens of photographs and I couldn’t possibly capture what it looks like, or the feeling of this whole experience. And those two ravens!

DH: They must know we’re up to something.

So anyway, there was an initiation of a kind. Jane had an extensive philosophy about this merging experience. For her it was directly a contribution, in Jungian language, to her individuation, the merging that experience really facilitated her individuation process to a more fully mature woman. She related the merging phenomenon as a substantial contributor to that process. These moments are very special moments that manifest things, psychically and spiritually.

CW: Do you feel more autonomous? More confident? It seems like it would give you something that nobody can take away from you.

DH: Yeah. For example, I’ve done a lot of work with couples and pretty crazy family situations. And even when I was an intern, all the other interns said, “You don’t really get bothered by anything.” I used to do co-therapy as part of my internship, and sitting in the room, all the women would say, “I feel so safe with you in the room” because I’d just be sitting there, not afraid, while all this interpersonal wilderness, this wild, human craziness is going on around me, and I’d think, “I know about this. I know about wildness. I don’t need to be bothered by this.”

So there’s that ground level, instinctual confidence. I don’t need to be afraid of this. I was ten years old walking down Cojo Canyon by myself. Why do I need to be bothered by this?

CW: You mentioned that you have a lot of stories, that every place speaks a story to you. Could you give me one example?

DH: (pause, thinking, etc.) One interesting one was…well, my father, he was kind of crazy at the Ranch sometimes…he gathered up all the people, the Ritz club people, there were maybe five families with kids of various ages…

CW: These were families of the original…

DH: You know, Bendy White, our councilman…Harwood “Bendy” White…he’s a councilman from Santa Barbara. Anyway, the Whites and the Hollisters hung out, he was a little older than me. His family would come up here. And there was a furniture store called Jacobson’s Furniture on Upper State, and Laurie Jacobson would come up here. And the Churchills…there was a group of people. Anyway, my dad decided he wanted to have a campout. He wanted to go up Bulito Canyon and then to what we used to refer to as the East Fork of Bulito. When you pop out of the oak trees and you start going east, right up there was a spring and some trees, and we all got in our cars and there was a flat area just below the spring, and it was one of these lovely August evenings, and we all drove up to the spring, set up camp, had dinner and went to bed, lovely evening on the Ranch.

Then, in the middle of the night a thunderstorm came in, pouring rain. Thunder, lightning, in the middle of August. A torrential storm. Everyone was sleeping out on the grass initially, and they now had to run and get into the cars and huddle up to get out of the rain and away from the wind and lightening. I ended up sleeping under a Willy’s jeep. It was cover, smelly cover, but cover. So that was a bizarre situation, rather disturbing to all, and people were fuming at my father.

Anyway, we got up in the morning and the hunters still wanted to go hunting ‘cause it had stopped raining. It was very misty and damp but not raining now.

CW: Isn’t that highly unusual to have that kind of rain in August?

DH: Oh, totally unusual. Since I’ve been here, I’ve seen only one other August storm, on my wife’s birthday, the 26th, about eight years or so ago.

CW: So this freak storm had to happen during the big campout.

DH: Everyone was so pissed off at my father for not predicting…I don’t know. So the story continues because I started hunting. It was very misty. Thick mist, couldn’t see but five feet in front of you. At the top of the east fork of the Bulito, there’s a flats area. If you continue, there’s a road that goes up and eventually it will come down Agua. I started walking up that road slowly, still immersed in misty fog and eventually reached the very top of it….

(Interrupted by noise and vibration.)

DH: Vandenburg. Something’s going on over there.

CW: It’s part of the collision of boundaries….

DH: So I had this moment where I was going through this thick fog and suddenly I popped out of it completely. I’m sitting on one of the highest levels of the Ranch and I can see there’s just a bed of fog and I can see way in the distance the tops of mountains like islands in the fog, an ocean of fog with mountaintop islands. It was so incredibly beautiful and mystical.

Then it got really wild. It started storming again. And I’m sitting out there with my thirty-thirty rifle, and I’m thinking, “This is not a good idea.” I’m really at a high point here, holding a metal rod. It’s like, hello Doyle…get the hell out of here. So I just sprinted back to the campsite arriving soaking wet from the rain now pouring again, and everyone was asking, “Where have you been, you idiot?” More or less that was the tone. I was probably eleven or twelve, just a young boy having these incredible moments.

And it continues, because we had to walk out. The clay, when it gets really soaked, you can’t drive on it…you’d just slide into the abyss. So we had to walk from the top of the east fork of the Bulito all the way down to the Ritz. My mother going through that was so mad. Your shoes weigh about forty pounds each.

CW: Frankenstein platform shoes. I’ve had that happen…

DH: Exactly. So that was just a little adventure. And I can’t go by there without remembering that. It is definitely a power spot for me!

A Jeep Excursion: Clint with Lincoln, Doyle (standing), David, and Charlie at the wheel

CW: Your dad was…

DH: Kind of a prankster, a bit. He loved the Ranch, but he wasn’t a rancher. He was a pediatrician, one of two pediatricians in Santa Barbara at the old Santa Barbara Medical Clinic. He would do his practice during the week, and we’d come out here on the weekends. So there was one night…another story…it was really windy, and we were all in the Ritz hotel and there was a group of boys there that often came out with us, so we had a collection of maybe six guys my age, maybe we were about nine or ten. Dad started talking about the ghost that lived next to the water tank up the hill from the Ritz. The wind was howling. We all got our little flashlights and timidly began creeping up the hill, it was one of those really windy dark nights, the eucalyptus and oak trees hissing away in the darkness, and just as we got to the top of the hill, on top of the water tank, blowing in the wind, there was this white ghost howling and swaying about on top of the tank. And we went, “Holy shit!” and turned and sprinted down the hill as fast as we could back to the house. Of course my dad had lured us into thinking this, had gone up there, climbed a tree, got up on top the water tank, and scared the be-Jesus out of us. He did things like that.

CW: But he very much loved the Ranch.

DH: Losing this Ranch killed him. I’ll just tell you that flat out.

There were four children…the two twins, Dad and Jane…then there was Joe Hollister, and there was Jack Hollister, JJ’s father, so those were the four children, and Joe was the one…he was a geologist…that got my two half-brothers, Charlie and Lincoln, interested in geology….he was the one that was groomed to take over the ranch when my grandfather, their father, couldn’t manage the ranch anymore. But Joe died of a brain tumor in his early forties. Then, not too far after that, Jack died, the eldest. So there was just Jane and Dad left, the twins. And Jane wasn’t here. She was up north doing her Jungian stuff.

So the only person who could take over, really managing the ranch, was my dad. And he was a pediatrician. So when my grandfather died, Dad quit his practice and started to try to manage the Ranch. He tried to do it from about 1961 when grandfather, the patriarch died, but all the other six families wanted to sell. They didn’t want to keep the ranch, they wanted the money, they never came here. So, the Ranch politics…it just became more and more dysfunctional and contentious.

CW: There were six families…

DH: All had shares. It was the Hollister Estate Company. They were Hollisters . Everybody had shares. I had shares. So they wanted to sell the Ranch. Dad was fighting that…and fighting that. Originally, Jane was fighting it too. Then, interestingly, and this is a semi-sore subject, but their father, my grandfather, had left more shares to Jane, more power to decide the fate of the Ranch than he left to my father. So ultimately, it was Jane’s decision that the family chaos was insane, this was impossible to resolve, there’s no way this Ranch can be kept, and it needs to be sold. The decision came down to her, and this was her decision.

Jane and Clint Hollister, early 1900s, in front of the Hollister House as it appears today (Photo composite by Kam Jacoby)

So she voted to sell. And that was the real rift. My dad was trying desperately to hold onto it, to find ways to keep it even after the decision to sell was made. He was the one that found, originally, this man from down South, Conejo Valley or whatever, who was a successful developer, and his name was Harris Goldberg. Goldberg came up here, saw the Ranch, fell in love with it, and said he wanted to buy it and keep it just the way it was, my father and our family could come up here any time we wanted to, and this seemed perfect.

CW: But in retrospect, aren’t you a little skeptical about that?

DH: I don’t know what would have happened. My dad felt he had found someone who would buy it and protect it. He was very obsessed with this. But then what happened, unfortunately, was that Harris Goldberg had one bad season down south…it was one of those rainy years…and his development just got trashed…he was in financial trouble, real serious financial trouble. He ended up committing what they call Hollywood suicide. He drank a bunch, took a bunch of pills, and killed himself.

So now the Ranch was floundering out there, and from there Macco Company bought it, and they went bankrupt, and it fell to MGIC, the mortgage guarantee investment company, so they took it over, and LaRue had been working to Macco and he came in and started talking to MGIC. They didn’t care, they just wanted somebody to do something, so LaRue came up with this hundred-acre vision…and here we are.

But my father was totally defeated by this. He really felt that it was his responsibility to preserve the Ranch. It was really sad. I watched him. He made a couple of attempts to get back into some aspect of medicine and psychology. He did a child development program at Stanford, and that didn’t fly. It was very sad.

CW: Did he ever make peace with Jane?

DH: Not really. They were really at odds.

CW: Families. There are variations of this everywhere.

DH: Everywhere. That’s why Bixby had to sell. Nobody got along. The San Julian is unusual. Jim Poett and that crew, they managed to keep it together. More power to ‘em.

CW: In all honesty, though…and I’m a relative newcomer…but I think this arrangement, the hundred-acre thing…I have often thought it’s an unusual and unlikely model that works pretty well.

DH: Yeah, I would agree with you. I’ve gotten to a place of peace about it. It was really hard to transition, though.

Speaking about transition, here’s another story. When I came back after fifteen years…Rick Sawyer invited me out here, and I hadn’t been out here for fifteen years. After the Ranch was divided up into the hundred-acre parcels, my father said to my brother and myself, “You wanna buy a hundred acres?” He asked us! We were all depressed about the sale of the Ranch, and you could tell that he didn’t want to buy a hundred acres. So we said no. If we can’t have the Ranch the way it was, we don’t want to have a hundred acres. That’s ridiculous. How can you transition from the entire Ranch to only one hundred acres?

At that point there was no visionary sense as to what that hundred acres eventually could mean. We were in a state of complete displacement, and our father was depressed. So we said no, and that was that. Nobody talked about it. We didn’t do any processing. We didn’t go to therapy. We just didn’t talk about it. We did a typical ranch family disconnect, disengage. Don’t stay with the emotional feelings of this. Don’t be sad. Just go ahead. It’s over.

Fifteen years later, after I’ve gone to college…I went to Midland high school, I boarded there, I went to University of Denver, I went to Cal …blahblahblah…and then I did my Santa Clara thing….so fifteen years went by. I never really thought about the Ranch much. It was completely an emotional cut-off.

So I come back to Santa Barbara to start my practice in 1980, and my father dies two weeks later. I was looking forward to reconnecting with him, and two weeks after I get back, he dies. That was a sudden thing, heart attack.

So, shortly after my father dies, Rick Sawyer invited me up to a clam bake, and I went, “What is a clam bake?” (laughter) So I went to Santa Anita cabaña, never having seen any cabaña on the Ranch to this point, completely weird, there were a bunch of people milling around, and Rick’s got some clams there, and some crabs from the eel grass on the points…it was a low tide situation. He’s yakking and cookin’ up a storm there. I had a couple of glasses of wine. The sun was just setting at Santa Anita, at the cabaña. I hadn’t been on the Ranch for fifteen years, so I walked over to the edge.

There used to be this beautiful slough that went from the tunnel out to the ocean, the final journey of the Santa Anita watershed. We used to spend weekends there, just like Lord of the Flies. We would drive our little go-cart car down to the slough late at night, night and camp out over the weekend, and hunt the ducks in the morning, maybe spend two days there by ourselves, just living off the land and the slough. It was an absolute power spot for us as kids.

So I walk over to the edge of the promontory there. The sun is setting, and these two blue-winged teal come in, and they just glide through the sun dusted air, then slide onto the glassy slough below me…and all of a sudden, I just broke open. It just poured out of me. All of this incredible grief pouring out of me while I asked myself, What have I been doing for fifteen years? How could I not have this in my life at all?

It was overwhelming. It was, like, oh my God…what am I going to do now? It was like I just cracked. All of this repression comes out.

Doyle at the Ranch, age 6

That was a flabbergasting moment for me. I never had even considered that one could experience such a depth of grief around losing land. I mean, I knew the grief of losing human beings through death, but the similar if not identical grief of losing one’s relationship to land…that was a concept I hadn’t even thought of until then.

It was all so painful, but on some level I knew it was better to experience the pain than not. I was more alive but it was heavily painful to be actively in touch with the magnitude of the loss.

I went through a whole psychological process, slowly but surely, since my father had died, and here I was. Wow. Back on the Ranch.

I soon recalled that Jane and Joe were up here at the Ranch. So, awakening to this fact, I contacted them. I came up to visit them.

CW: Were they welcoming?

DH: Oh, totally welcoming. They were absolutely welcoming. It was very funny because I remembered this road, De la Cresta, was terrible as a kid, recalling our hunting expeditions decades earlier, and so I came up in my wife’s Saab, up Cojo and up Cementario, a nightmare of a road then…in my wife’s Saab. I almost ruined her Saab, but I got up here, and from that point on, progressively, I became more connected to Joe and Jane.

CW: And you found your way back.

DH: I slowly…they could see and understand…they’re psychologically sophisticated. They knew my father had died, and I’m sitting in front of them, and I’m talking to Jane, who’s my father’s fraternal twin, and she’s a very animus strong female…she’s got a good strong male side. I’m sitting there talking to her, and it’s literally like talking to my father, only in female form. All of this projection stuff started to happen. And I was her brother’s son, who was really connecting to her. I was interested in psychology…so…it all just started to happen.

Jane Hollister Wheelwright, early 1980s

CW: Maybe a way for her to make peace with him too?

DH: Oh it was totally a mutual process. She was talking to her brother through me, and I was talking to my father through her. It was this incredible connection. And it just progressed. So they decided…’cause Joe had a little cabin over there, that was part of his man-cave…so they said, we’ll give you one one-hundredth ownership, so you can come into the gate anytime, and you can go over there and stay in the cabin. So from that point on, I would come up here. I’d bust out of my practice and Santa Barbara and come up here for the weekends as much as I possibly could, and I began gradually to move through all of that anger and sadness, little by little.

It was so hard for me to go through the gate! (laughter) I would have such antipathy for that gate. I had to make it into…I had to somehow alchemically find the philosopher stone in that gate, transform the base metal shit of that gate into a higher order of emotional maturity within myself. The gate was symbolically the antithesis to the total freedom I had up here as a kid. I would come to this gate that marked the symbolic end of freedom and the childhood experience. So I would have such angst, well really rage, going through that gate, that I had to befriend that gate, befriend the psychological enemy.

Even to this day, I make a special effort to really connect with the gate guards. (laughter) I religiously try to remember their names…and I’m terrible with names…and I make sure they remember my name. “Hi, Doyle.” They know I want to be acknowledged for being Doyle. And I acknowledge them each by their respective names. It’s very important for me do this.

CW: It must have been easy when Michael Giorgi was there. He understood that the gate was a point of transition from one world to another.

DH: That’s where Michael and I really started to connect. I started talking to Michael, and I’d be sitting there at the gate for five, ten minutes talking to Michael. ‘cause he’s a ranch kid! He totally gets it.

CW: And he knew that when you came through the gate, it was time to get out of that other space and notice what was around you.

DH: He’s a very spiritual man. I can talk to him about this stuff, and he totally understands. He knows what merging is. He has a different experience, and a different way of talking about it, but he knows exactly what it is.

CW: He’s a natural merger.

DH Yeah, he’s a natural merger.

CW: I haven’t had any comparable experiences, but I can empathize with how complicated your relationship to this place would be. You inherit this sense of exile, I guess. Like that was ours once and now it’s not.

DH: It’s a sense of displacement. I felt displaced from my homeland.

CW: But in a way, aren’t we all exiled from something? Each of us has something in our past we have to finally learn to let go of, and gracefully transition to a new phase. I’m always interested in how people navigate these transitions and what wisdom they have acquired. What have you learned from all of this?

DH: I’ve learned how to sit with grief. I’m very comfortable with sadness. In my practice, I would say one of the assets I have is that I can sit with loss, whether it’s loss from death, divorce, or any place emotional where people experience loss. I have learned to sit with that in my own life, and that’s really helped facilitate me being able to sit with other people in tremendous pain around some experience of loss. I’ve had people sit in front of me who have lost a child, a parent having to suffer through the loss of a child is just tremendous…so I’ve learned about sitting in the darkness of pretty substantial grief based on having gone through this whole circle: being here, losing here, and coming back to here. I wouldn’t be able to be here if I didn’t stay with my loss. I would have disconnected. So it’s taught me a great deal.

CW: That’s huge. What you said really connects with me. I’ve been going through a hard year myself…starting with the death of my mother, other things, completely different things…and for a time I just wanted to make the pain to go away. I thought, I just don’t want to feel like this anymore. And then there comes a point where you realize, no, I feel like this, what I have to do is contain it. Carry it gracefully.

DH: You feel it— but don’t be it. If you become it, then you’re going to be possessed. Overwhelmed. If you can feel it, you can let yourself filter it. Not be it. When you become it, you are a victim person.

CW: So if this journey taught you that, that’s an extraordinary gift.

DH: Right. That’s something I have learned, the gift in it all.

CW: It’s nice too that you can turn the wisdom outward in your practice and help others.

DH: Some children champion the causes of their parents. I think that I, by doing this, by getting back here, I indirectly helped my father. Symbolically. In the other world it will be absolutely healing for him, the fact that I am now living here in the wild northwest corner of the old Hollister Ranch. That I live here I think is very soothing for him.

CW: God, I hope that’s true. I sometimes wonder if it’s possible to sort of retroactively fulfill the dreams of the people we loved who weren’t able to…can we do that for them.

DH: It happens all the time when people are invested in this in a conscious way. I think that part of my mission was to heal my father’s wounded-ness, that which killed him, to heal that on some familial level, indirectly, through my evolution and reconnection to the land here…

CW: Even the very fact that you are at peace and have found some kind of contentment…what parent would not want that for his son? You have to just let yourself be happy. You have to give yourself permission and know that your parent would have wanted that…don’t you think?

DH: It’s the mini-version too of that memoir I’m trying to write that’s about me but not about me at all. Even though the memoir is a container for my stories and my process, it is really about what happens to us as humans if we disconnect from wilderness. There’s my story about being immersed in nature as a child, and losing it, being disconnected from it, and then reconnecting as an adult, and that’s a different kind of connection than the child connection.

But the memoir is a mini-version of what’s going on with the planet. If we don’t do something…you know this…if we don’t pay attention to the wild and reconnect to it from our self-exiling unconsciousness, if we don’t reconnect our interior nature to our physical nature, our planet, we’re terminal.

CW: I love that your memoir would mirror that, because that’s such an important message. What scares me is that I feel we are all in a state of grief right now, and we don’t even have the name for it. We’re all either anticipating or experiencing the loss of our habitat. It’s very worrisome.

DH: It is. When I sit in that space and consider that, I almost can’t bear it.

CW: That’s why your story really matters. It gives a tangible way of seeing it. I think we forget how ill we are if we are disconnected from the natural world. Sometimes we don’t even know it…

DH: How ill we are. Yes, for fifteen years I could nave diagnosed myself as suffering from a generalized anxiety disorder and depression, though I didn’t know it when inside it…

Talk about instincts. I work with people and I watch how progressively they are less and less attuned to their instinctual life, and so the craziness, the interpersonal craziness, the personal craziness, all of the fast-paced technological focus of our world that is now taking us into virtual reality…it’s not really reality…so I watch this happen symptomatically, people slipping more and more into anxiety and depression, displaced inside and outside.

My little story resonates with the bigger story that’s going on. I try to present: what is being lost here? Just by my own personal experience of losing the connection to wilderness and then coming back to it, and realizing, “Oh my God. What happened here?”

CW: It's a story that needs to be told.

DH: I’m working on it.

CW: That theme is more crucial than ever. It’s urgent.

DH: We’re not really understanding what we’re losing.

CW: Exactly. But what happened to you is oddly illustrative.

DH: It’s a metaphor.

CW: Well, I’m almost satisfied that we’ve gotten to the heart of things here. We’ve covered a lot of the questions I usually ask.

Okay…here’s one. What is your source of strength?

DH: My instincts. That’s absolutely it. All of my experiences growing up here as a kid, the interplay of my psyche and the wilderness, there were consistent initiation processes that took place that really grounded me with a sense of my instinctual life. Jane talks extensively about how connected she was to her instinctual life, and that was incredibly grounding for her. She was a very grounded woman, solid as a rock.

CW: And “grounded” means…stability? Knowing who you are?

DH: Really comfortable in her prima material, in her primitive life. She always had a lot of anxiety interplaying with social culture, but she was fearless in nature! I mean, she was a little five foot one thing, and ‘til she was practically 93 years old, she would go up the driveway for her evening walk. Joe would sit on the bench…that’s as far as he could go…and she had this little chain that had a sailboat horn on it in case she saw a mountain lion or a bear, really loud, and some knives and a flashlight, and she would walk by herself, all the way up, say, to that saddle, and as she goes she would put acorns into the side…she loved the oak trees. She was an oak tree.

CW: Are there any particular oak trees you know she started?

DH: They’re all over the ridge. All the oak trees coming down the driveway were planted by her. There weren’t any oak trees when she built the house. It was all rather arid and flat. She planted these trees. They’re Jane’s trees.

But she was fearless in that regard. And her confrontation with her unconscious, with her dreams was religious. Her Tepitates Journal is somewhat of a dream memoir, over a thousand pages long, edited by Betty Wheelwright. So she was fearless in taking her own unconscious, her own primitive nature. I think that came from growing up so close to physical/external nature.

CW: So we’re all born with these instincts, but in some cases we have more opportunity to hone them?

DH: We all have the opportunity to be in that connection with that level of life, but the world…the socio-cultural phenomena taking place…is just completely distracting us from that. You have to be quiet, and still, and alone. Romantically, people want to be in nature, but they find it really hard to be alone. I don’t have any problem being alone. I don’t really need to be in conversation with people. I do like people, though…to a degree. (laughter)

CW: I think when you’ve been out here for a while, it becomes more difficult to go back out into that world. You become more sensitive to how crazy it is, how noisy.

DH: It’s true. My anxiety goes up every single time I leave here. I delay, I delay, I delay…I go in on Monday night, stay in my office on the Mesa Monday night, I work really hard Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, and I usually come back Thursday afternoon. But every time I go back, right around Winchester Canyon, the traffic picks up, my anxiety picks up, and I wonder, why am I still working? What am I doing here?!

CW: Monte and I did it for years. We had a very schizophrenic life. It’s difficult going back and forth.

DH: It’s always easy to leave town and come back here. I get so excited. To get “out” again. It’s a complete sense of relief. My imagination kicks in…I just feel excitement. I feel it in my solar plexus, just to come back here.

CW: This is your place. For me, it feels so unlikely that I should be here, but I’m so grateful. Wherever I go, I’m never disappointed to come back.

Maybe another question or two before we go back down the hill, although it seems we’ve covered most of these. What fundamental experiences have shaped your world view?

DH: Not everybody gets that experience of growing up on 15,000 acres completely free, no supervision, really. We could go anywhere we wanted and do anything we wanted to do. It was really a blissful childhood here. I feel completely blessed that I had this experience.

And yet the degree of freedom I had has also been a sort of curse, because I’ll never have that kind of freedom again. I mean, I’m very appreciative that I had it, but for my brothers and myself, there’s always that place of wildness that we don’t know where to let it out. It’s gotten us, in various ways, into trouble. All the Hollister boys in one form or another have found trouble. Some of it’s been good trouble. Good trouble is good in the long run. But some of it has been bad trouble! It’s all about being pretty wild, and trying to manage that wildness that was so pure growing up. It’s not been easy.

It’s not been easy for others, either. It’s caused my wife trouble…she’s been an absolute trooper. I probably wouldn’t be here on this property if it weren’t for her. She did a lot of practical negotiating with the family, where I was so raw. I just wanted to be here. She was the one who helped negotiate. Joe and Jane were going to sell this property, so here I was again, confronted by another sale. “You’re kidding me. I’m gonna lose it again?” Please! I didn’t have the money at that point. So Joanne went to work, and negotiated with Linda and Jane, and John, and Jane wanted me to have it, ‘cause she knew I “got” it, but they needed to have some financial resolution. Linda lives back in Maine, John lives in Pt. Reyes.

So we worked something out, where I would take responsibility for the place, and when I had the money, ‘cause at some point I was going to inherit some money, I could pay them. But I was just a raw nerve, and Joanne was able to be more detached about it. So that was an interesting moment.

But the wildness has not been easy. I wouldn’t have traded it for anything, but it’s a hard thing to harness in a civilized world.

CW: So you have to channel it into your writing.

Well...shall we do any more questions? How about a turning point in your life?

DH: A turning point was when I burst into tears at Santa Anita.

CW: At Rick Sawyer’s clambake!

DH: He opened the door, and that moment changed my life. It wasn’t a sure thing that I was going to be here. I felt really lost after the grief invaded me. One of the chapters in my book is “On Being Lost”…

Quick story…I went on this insane trip to Wyoming. Gretel Ehrlich and her then-husband Press Stevens, had some property in Greybull, Wyoming…and I went to Wyoming to look for a ranch to buy. I got all the way up to Gretel’s place and was following Press around, he had sheep and cattle…a nonstop kind of guy, pure cowboy…and then I simply had to walk somewhere alone. I had to go wander. Press said, “Well, go that way.” So I got up one morning and went up this canyon further and further into the mountains and then started going up this creek, and I followed this creek higher and higher into the mountain until the brush is closing in on me, and I couldn’t go any further. I turned around and I could look out to the valley out there in front of me, which has sort of a moonscape before you get up to the upper mountain, kind of a desert-y ash look, and I was sitting there, and I said to myself, “What are you doing, Doyle? What are you doing up here? This isn’t your landscape. What are you doing here?” I realized how lost I was in terms of being home. I could possibly buy a ranch in Wyoming, but I wouldn’t be at home. This was a profound, and, once again, painful realization…

I came back, and I went into my office and did my work when I got back, and one evening, the sun was going down, and I was locking up my office on Micheltorena Street, and this blast of wind came through this oak tree that was hanging over my office, and I thought, “This is my home.” The oak trees, the wind…the golden dust color of the rolling California hills.

I thought, “You can’t go buy some property, even if you could afford it, in some other state. You need to find something here.” So I just became more aware, more realizing, that my inner landscape was this landscape. Something needed to happen here. And fortunately, it did.

CW: So being lost helped you find your way.

DH: If you don’t go with it, whatever crazy impulses you have, you won’t find your way. I did crazy things trying to figure out something that was essential. Doing crazy things, just sort of following my impulses and instincts, it all ended up in me being here. I had to get into trouble, but this is what I mean by getting into good trouble. It all makes sense to me as I look back. It all makes perfect sense. But as I was figuring it out, it was insane some of the things I did.

CW: I’m sure you know the line from T.S. Eliot: “We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.”

DH: Right. Exactly. Know it for the first time as an adult, different than how I knew it as a child…

One of my favorite lines is from John Muir: “I only went out for a walk, and finally concluded to stay out till sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in.”

That’s the merging experience we’ve been talking about. That’s the title of my memoir. I Only Went Out For A Walk. The quote captures that moment I walked out above the Santa Anita at Sawyer’s infamous clam bake...and then, of course, it describes the merging experience.

But I don’t want this memoir work to be just about me. It’s a story that has me as the protagonist, but it’s a bigger story. And it’s a relevant story for us right now.

I feel like I’ve gone through some kind of heroic journey and I didn’t get killed. I feel really proud that I’m living here. I didn’t stop or quit, didn’t give up, just kept on going, staying with that difficult emotional process, and I made it here. This is what we all need to do with the planet, not quit the journey to heal it, as painful as that is to face what is happening to it. But I’m a pilgrim. I’m always looking for the next sanctuary.

CW: Your life now seems congruent with who you are. How would you like to be remembered?

DH: (pause) That’s a tough question. Obviously, I’d like to be remembered by my family as having been a good father, even though, you know, having flaws, but overall being a good father. Being a good husband…having flaws, but overall being a good husband. And now that my son has had a son, being a good grandfather, a good elder…

I’m a loyal person too. I think I’ll be remembered as a loyal friend and family man. And I always have this sense of wanting to contribute something to the planet. That’s the memoir, that’s the poetry. I need to get my memoir out, even if just for my children, and maybe someone beyond the family would say, “I learned something from that Hollister guy.”

I don’t know…I would just like to be remembered, as, at least, that I had a statement some people could latch onto and get something from in terms of the importance of nature. If someone could say, “God, I really connected or reconnected to the wilderness inside and the wilderness outside of me, and Doyle Hollister helped me do that.” Even if one person said, I gotta thank that guy for what he made me see, in myself and outside of me.

Something like that. That would be good. Even one person. And I don’t know if that’s gonna happen, but it feels to me that there’s an experience I’ve had that means something beyond me, and I want to be able to say something about that and maybe it will be heard…

So I do hope I can manifest something that will take the personal journey into a collective statement in some way and other people will get something out of it for them that will enrich their lives. It’s all about psyche and nature, internal and external nature, that’s totally my gig. That’s what Jane was about. I see my life as literally mirroring her life in a lot of ways, and ending up in the same Place…capital P….

I want to really condense the essence of what she was trying to say, which I think is so important, and I want to do something there personally, that goes even beyond what her work was is about…that’s gonna be the frontier for me. That’s the next sanctuary. That’s where this pilgrim is going next.