Trying to capture the essence of Frank Van Schaick on a few sheets of paper is depressingly futile; he was too many things and so influential to countless people, especially the generations of children he taught.

Room 10 at Wilson School was no ordinary place; it was Van’s Room. We had our regular studies, of course, but they occurred in a room full of wildlife captured on many trips, a room adorned with Greek statues and horse pistols. Navajo sand paintings and prints of the great masters hung beside our own works. Across the hall was a large closet allegedly for coats and lunches, but it contained tools and work benches on which we manufactured all manner of projects. Everyone had to make an ash baton and “conduct” the class music lessons. Best of all, we made bows and arrows from scratch and took them on our camping trips. Room 10 had no regular pencil sharpener; we used our knives, just as Van did. Van had us in noon league sports and after school we practiced for the Saturday games against other schools, where winning was good, but sportsmanship was paramount. We agonized over a class Constitution, then we lived by it. Van was a great one for democracy; he taught it and lived it.

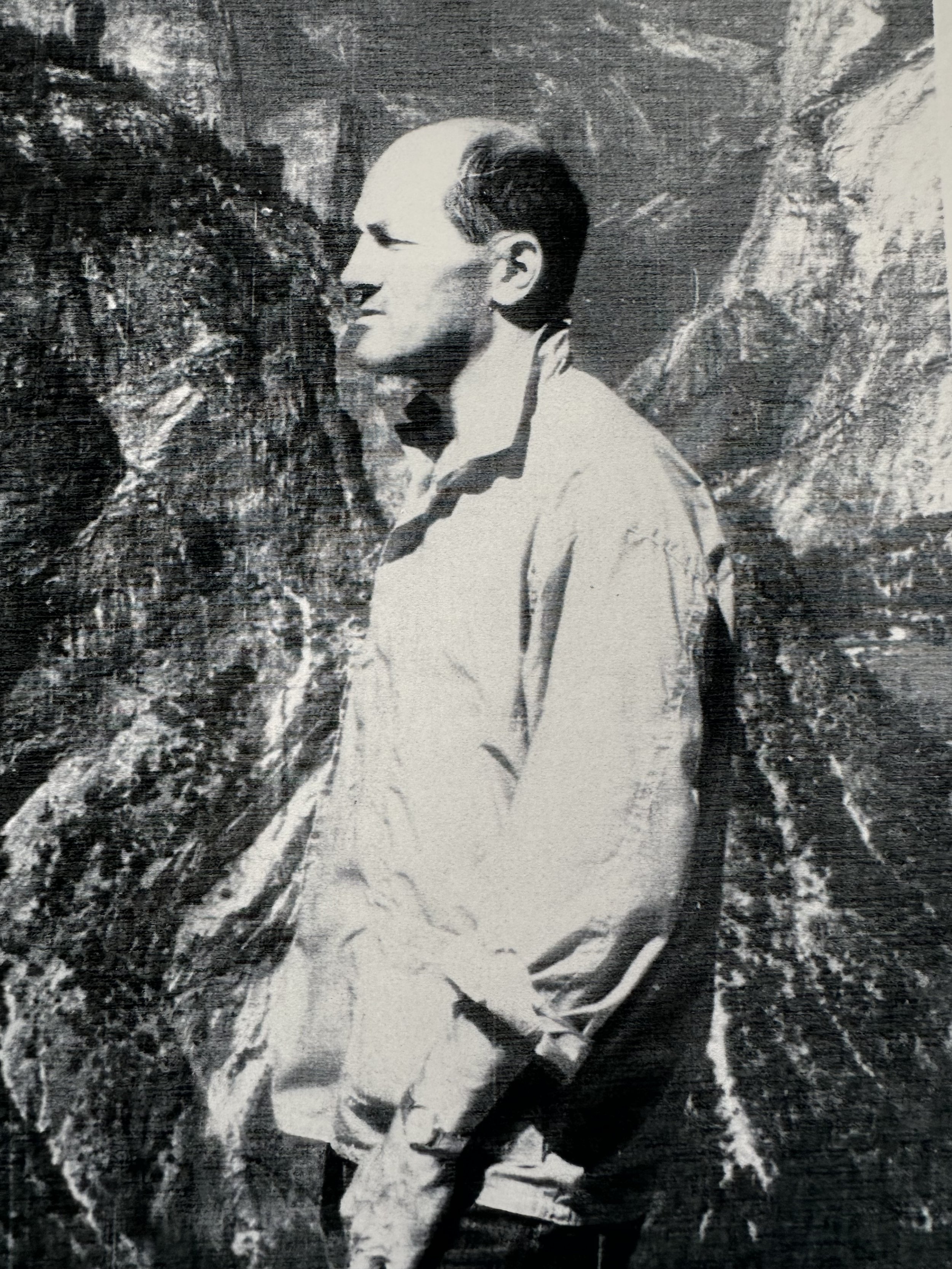

Van had a calm forcefulness and a strong will never imposed; he simply set clear examples easily followed. Even today, 50 years later, former Room 10 students will ask themselves what Van would have thought before settling on their own course of action. His keen intellect was obvious, and as we grew older we appreciated his abiding wisdom. Van’s character and personality were perfect for the classroom, but more so for the wilderness, which, I think, Van assumed was another classroom more suited to higher learning. Love for his family was intense, but I doubt he was ever more content than deep in the woods or high in the Sierra, especially with a group of kids “doing all that neat stuff,” as he would put it, “learning to take care of themselves.”

I recall once, years after Room 10, stopping by his place for a visit. Van had yet another group of children down in his woods —Van had yet another group of children down in his woods —cooking, camping, tying knots, and studying wildlife — and I asked his wife Lois how he could put up with all of us over so many years. She replied, “He never met a kid he wouldn’t bring home.”

He was the recipient of countless accolades and awards, all graciously accepted, then never mentioned again. Humble legitimately describes Van, as does Man of the People, but he was by no means common. I once chanced upon a retired Stanford professor and mentioned that my sixth-grade teacher was a graduate of her institution. On hearing his name, she became excited and said, “Frank Van Schaick! He was the most gifted student I ever had.”

Van was ever a man of words and good literature, surrounded to his last days by stacks of books, especially of the West, Native Americans, natural history, and biographies. He wrote the “Nature Walks” column for the News-Press for many years, and co-authored two volumes with his good friend Dick Smith. After retiring, he wrote a memoir of sorts, Home of the Wilson Wildcats: Life and Death of an American Elementary School. He showed me a card he received from education guru Mem Fox; its essence was simple: “Mr. Van Schaick, this is the best book on education I’ve ever read.”

Van said teachers were buying it, then laughed, and said, “But not administrators, damned fools,” an epithet seldom heard by him and usually reserved for Congress.

Van topped off his literary excursions during our backpack trips. The last night out we’d build a fire along some quiet stretch of river and Van would tell us a story, usually something obscure from the fringes of Western literature. We’d lie there beneath the stars, mesmerized, wrapped in a special magic until the tale ended and the fire died.

The last pack trip of the summer was special because he’d bring his wife Lois and his daughters Susan and Mimi. Lois was every bit his equal and toted around more personality than ten normal folks could handle. When Lois showed up as a young teacher at Wilson School, Van was knocked off his feet. They both loved jazz and danced to favorite records before school in Room 10, a magical place in every sense. They lost Susan far too young and raised her children John, Vicki, and Jamal. And Mimi, that cute little imp and tease of so long ago — now a grandmother herself and mother of Jessica — sat beside her father the night of June 20; Van spent 94 years on this Earth and is gone too soon.

Bruce Brownell, the author of this tribute, followed the example of his mentor and himself became a beloved and unforgettable teacher. You can read an in-depth interview with Mr. Brownell at this link on The Living Stories Collective website.