Early in 2019, I set out with Karen Jensen and Kam Jacoby to interview several Los Alamos residents about their experiences as quilters, or the stories connected to quilts that they owned. The quilts were then hung on display at the Los Alamos branch of the Santa Maria Public Library. But when we embarked upon this project, we did not anticipate that we would also be getting a glimpse into a vibrant culture, one through which run common threads of resourcefulness, creativity, and generosity. We discovered that the act of giving is implicit in quilting, and most of the quilts we saw had been made as gifts for others. There were quilts that celebrated weddings and births, quilts to comfort the sick or bereaved, and quilts to be passed along to future grandchildren. The quilting community seems to be characterized by big-heartedness, and everyone we met was welcoming and gracious, sharing their work and their stories with pride and affection. Even a quilt initially created to add color and comfort to its maker’s home is likely to live on in the hands of a descendant, for it is in the nature of a quilt to travel through time to embrace a subsequent generation.

Quilting is certainly a form of artistry and a traditional way to transform scraps and materials into something both useful and beautiful, but we had decided at the onset that this exhibit would be less about the technical aspects of quilting and more about the meaning of it. We were surprised nonetheless by how truly meaningful it is, and by how readily emotion and sentiment rose to the surface in the course of our visits. More than once, we hugged good-bye with tears in our eyes. “Every quilt tells a story,” said quilter Charlene Abeloe, “That’s the beauty of quilting.”

The stories these quilts tell are about remembering, about joy, about connection and comfort. They are about transcending a life span and making from fragments something beautiful and enduring and greater than the sum of its parts. But the word we most often heard was “love”. These quilts are labors of love, imbued with love, given to others as an act of love–and they speak of love to all who listen.

Charlene Abeloe

Charlene’s work demonstrates that the beauty of quilting is not only the stories the quilts contain, but also in the love and the giving. In her nearly thirty years of quilting, Charlene has created almost all of her quilts for others, donating them to children with cancer, ailing friends, or worthy organizations. Her husband Carl proudly tells us that she made a quilt every month for three years to raise money for the Parkinson’s Association. There is a quilt she made for her brother after his wife died, which includes images of her sister-in-law as a young woman and later in life, framed by rich dark tones of blue and brown and ivory-colored flowers. There is a Lewis and Clark quilt, each square based upon the drawings of schoolchildren, and a heart quilt she made as a raffle prize for her quilting group that her fellow quilters made sure she “won”.

On Charlene’s bed is a quilt her mother made for her from the skirts and blouses of her childhood, the faded cotton colors in each Dresden plate harvested from a favorite outfit. It was this quilt that awoke Charlene’s own artistic impulses, and when she retired, she taught herself the craft. Her first creation was a quilt of crows and sunflowers she made for her daughter in 1990, as sunny and bold as a bright fall morning. She enjoyed the process so much, she formed a quilting group at the First Presbyterian Church in San Luis Obispo, and she has been an avid quilter since. A binder of photographs is her only record of the scores of beautiful quilts she has lovingly given away, a testimonial not just to her artistry, but her generosity and kindness.

“The quilts let me express what I felt,” Charlene explains. “I’m very quiet. I don’t talk much. But I use the quilts. They speak for me.”

They speak eloquently.

Madeline Jex

It’s obvious to anyone who ever browsed at her old store, The Gentleman Farmer, or has stopped into her current location at Sisters on Bell Street: Madeline Jex has a great eye for treasures. The gorgeous 1920s quilt that she is sharing with us here had been left unfinished in a box in her mother’s closet, but Madeline recognized its potential immediately. It had been started by her paternal great-grandmother and abandoned.

“When I found it, I recognized it as special,” says Madeline. “I wanted to see that quilt finished, and I knew my mother could do it. She was an excellent seamstress, born in Belgium, and schooled in Brussels. I have all her diplomas. Everything she did was excellent. She made all of my clothes and she knitted too, with all the stitching meticulous and perfect.”

The great-grandmother who had started the quilt, Elizabeth Stammers, was from a wealthy family in England, but had run off to Canada to escape an arranged marriage that was not to her liking. Madeline’s mother, whose name was Reine Hastie, was initially reluctant to take on the task of completing the quilt – “It’s a lot of work!”– but Madeline beseeched and cajoled, and eventually Reine finished it as a reward to Madeline for a difficult accomplishment.

And so the stories of two spirited women, one from each side of Madeline’s family, are stitched into the fabric of this quilt. “I like knowing that my great-grandmother chose this pattern and those colors. And if she was anything like my grandparents, she was probably a lot of fun and had a great sense of humor.”

“It was the Roaring Twenties,” Madeline continues, “a gay and festive time, right after World War I but before the Depression. The quilt has so much life in it. All of those bright colors. I love the red! The polka dots! The pattern of fans!”

The quilt has been carefully packed away for decades and looks brand new. Madeline is letting it see the light of day for this exhibit, with hopes that visitors will enjoy its aesthetic beauty and the intrinsic optimism of it.

When it comes to quilts, there’s always a story. This one speaks of happiness.

Sandee Adams

You can feel the creative energy as soon as you enter the home of Sandee Adams and her husband Burton. Originally from Minnesota, they built their own house, lived on a shoe string, and learned how to do things themselves and make use of whatever they had. Quilting is a natural outgrowth of this inclination, where even scraps have value, and somehow the beautiful whole becomes more than the sum of its parts.

The original quilt in Sandee’s collection belonged to her Swedish grandmother. It’s summer light, with no batting, and its colors are pale. She also shows us a beautiful hand-stitched quilt she made during the building of her house, in which bright maple leaves and dark borders evoke both sturdiness and cheer, and a flower quilt, each panel a hand-painted work of art.

“I would love to see more young people learn to quilt,” she says. “Maybe as a community activity through the senior center, we could bring in kids and teach them, girls and boys, maybe at the summer program. I’d like to see more kids getting into it and knowing what it’s about. Quilting is an art. It’s a love. It’s a joy. It’s not something we should lose.”

Cathy Trawler

The first quilt Cathy made was in 1997 for the birth of her granddaughter Emily, and so began her quilting odyssey. One of her loveliest creations is a heart quilt–she calls it heartfelt–that hangs above her bed. “We moved into this house in 2003,” she tells us, “and I just needed something for that wall.” It’s an arrangement of soft colors and angular hearts, and it sets the mood of the room.

Cathy mostly machine quilts and relies on others to complete the batting and stippling. She modestly claims that pre-assembled kits make it easy to choose patterns and coordinate colors, but her taste and personality are stitched into all of her creations. A Christmas quilt on her bed is done in traditional red, white, and green, with a surprise band of blocks on the back, added when she ran out of backing. She shows us quilts in various stages of completion and brings out one in an old pattern called “Churn-dash”, done in warm tones, which we later contrast with an interpretation done in a cool bright batik print by her friend Marla. Fabric choice can change the whole look.

Most of Cathy’s quilts are destined for her grandchildren, but lately she has been keeping and enjoying them for herself. “I love the creative feel of quilting,” she tells us. “I used to paint and draw, and I wanted to do something different. This is another way of being artistic, but I can use it and keep it.”

Marla Gravitt

Marla began quilting after she quit work and wanted to find something different to do. She learned techniques in classes, participates in a quilting group that meets weekly at the senior center, and has become quite accomplished over the years, but as with most quilters, the majority of her creations end up in other hands.

One of her first efforts was a lap quilt in a log cabin pattern, all done by hand. She made a quilt for her granddaughter’s sixteenth birthday entirely of scraps, then used the same colors in a different pattern for a great-niece. She shows us an “attic window” quilt that gives the illusion of viewing outdoor scenes through panes of glass, and another quilt she refers to as “Jim’s Quilt” because her patient husband did all the cutting. She has a lap-sized version of the Christmas quilt we saw on her friend Cathy’s bed, but done in antique colors, as if infused with tea, and the Churn-Dash pattern interpreted in batik scraps she already had and wanted to use.

Almost all of Marla’s quilts were made and given away for milestone events such as weddings, graduations, and births. Now she is going through her fabric scrap stash to make quilts for future great-grandchildren. “No names, no dates,” she says. “Noni will be gone, but she left you this.”

We try to estimate the time it takes to complete a quilt, particularly in Marla’s tiny hand stitches, and can only conclude that it takes a lot of hours. “What it takes a lot of,” says Marla, “is love.”

Gary Mortholé

Gary’s three quilts are mysterious, although many clues and stories are stitched into them. Dated 1888, 1915, and one unknown, they belonged to his maternal great-grandmother from Chippewa, Ontario, near Niagara Falls, then to his mother, and were given to him by his father after his mother passed away.

All are done in redwork embroidery, a type of art needlework that gained popularity in the late nineteenth century, with a colorfast thread dye called Turkey Red. Like illustrations in a children’s book, there are whimsical birds and animals, flowers and scenes, and occasional names and messages. One wonders, who was Caroline, and why is her name adorned with peacock feathers? And why does Minnie have a frog on a toadstool? Aunt Emma, in a central panel above “Home Sweet Home” with her cleft chin and arched eyebrow, certainly looms large. One of the quilts is more like an overlay, but because it has no backing, we are able to see the perfection of the embroidery on the reverse. Another is an alphabet, with the name Rhea, which Gary recognizes as a family name.

The stories are hinted at, rather than told, and the quilts have prompted Gary to do some research into his family history.

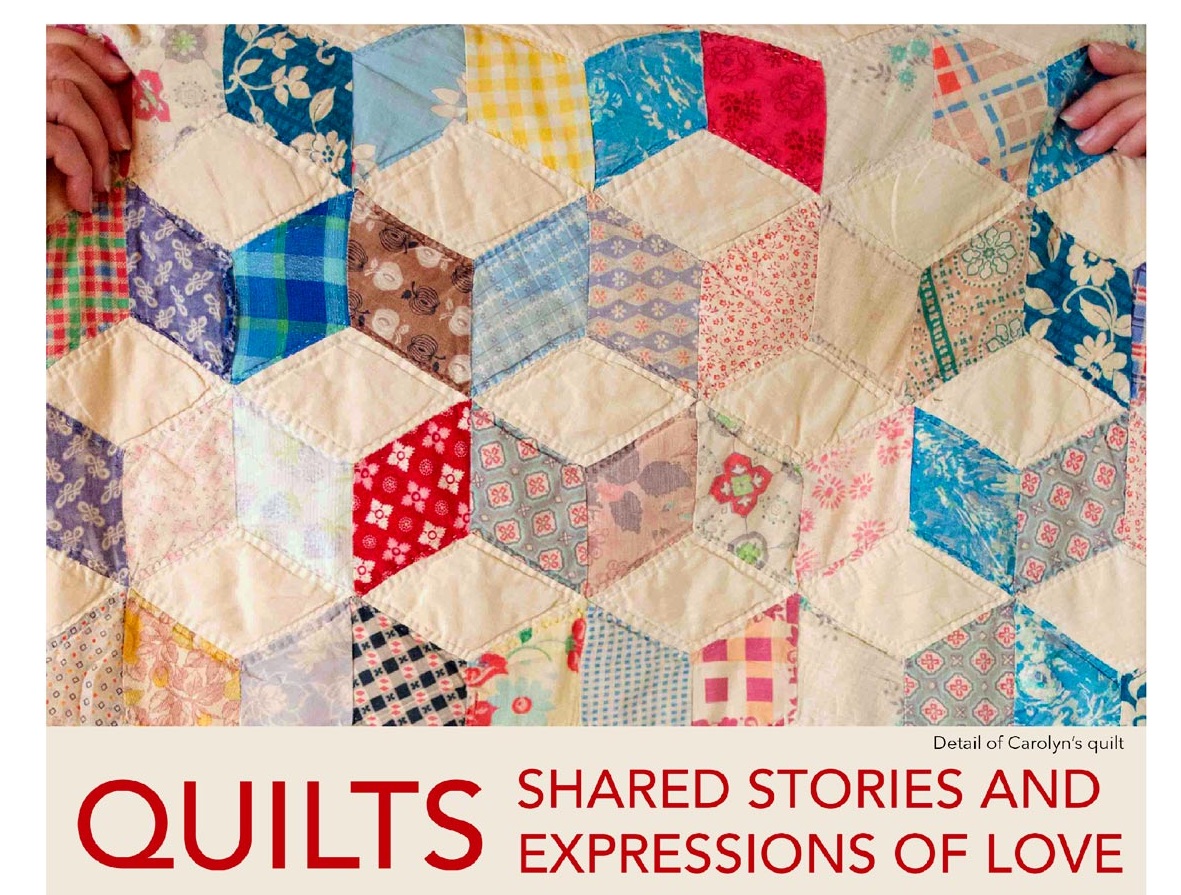

Carolyn Mortholé

Carolyn’s mother made a quilt for each of her children from scraps of their baby clothes and the maternity clothes she wore, and Carolyn has her own and one of her sibling’s. The 1950s fabrics have faded to pastel, and time has softened the cloth and turned white to ivory, but the tidy stitching and symmetry still convey a fresh and cheerful look. It’s a mother’s tender legacy, a hug through time for each of her kids.

Suzanne Reed

Suzanne’s mother taught her how to sew, and as a little girl, she watched her maternal grandmother sew quilt tops together, but she is largely a self-taught quilter.

The first real quilt she made is a patchwork of memories, from remnants of her mother’s fabric stash to scraps of fabrics from clothes she made as a kid. It is imbued with her spirit, as its maker, but also that of her mother, who loved sewing, and her woodworker father. She hopes its bright colors will bring a smile to the face of whomever eventually acquires it.

Suzanne feels that every quilt is unique, because even if you use a pattern, fabric choices may vary, and the quality and style of sewing are individual.

“Quilting gives me a sense of purpose,” Suzanne says. Many of the quilts I make are gifts, and those that I keep fill a creative need. It also makes me feel connected to generations of not only my own family members, but to many generations of women who sewed and quilted before me.”

Jennifer Hooten

Jennifer’s gorgeous quilt is vaguely Escher-esque, its triangles shifting into parallelograms, diamonds, or intersecting bands of color depending on how one looks at them. “I loved the simplicity of working with solids, but also the complexity that came with the sheer number of triangles,” she says.

For Jennifer’s mother, who has been quilting for over thirty years, quilting is a “mental health activity”, and she made sure that Jennifer learned the craft. To this day, they get together annually on a North Carolina beach, along with a sister and two aunts, to work on projects. This particular quilt was begun on one of those trips. Jennifer, pregnant at the time, pieced a few rows together, then put it aside for a while after having her baby.

“The quilt is imbued with the spirit of my new self, as a mother. Motherhood has me longing for simplicity, and yet wanting a spark of vitality and brightness amidst the ordinary bits of daily life. The plain, solid triangles offered the simplicity, but the hexagonal quilting gives a hidden surprise for those curious enough to look closely. This now hangs in my living room and brings the brightness and liveliness I hoped for into each day.”

Karen Gearhart Jensen

Karen’s mother, Helen McCausland Gearhart, had a sewing room in the basement. “It was just her space,” says Karen. “I remember she would cut, then push the unused edges onto the floor, so there was always fabric all over the place.”

Karen, an artist, was influenced by her mother’s sense of design, inheriting her bold, graphic sensibility and eye for patterns and botanical shapes. She looks at her mother’s creations now with respect and admiration for their skill and artistry.

One of her mother’s creations is a sampler, in which the quilter chooses a certain number of patterns, and each block is a different one, as opposed to geometrical shapes sewn together. All of the piecework is appliqué in this quilt, so the flowers and butterflies have a three-dimensional look. There is also a small Amish style quilt, finished in about 1983, in bright clear reds and blues.

But Karen’s favorite is a stunning hand-quilted bed spread of bright flowers on a black background. “This definitely brings me closer to my mother,” says Karen. “Even though I didn’t see her make this quilt, I saw pieces of it in progress over the years. She put this one on her bed. She was proud of it. And it’s the one I really wanted.”