Ernest Pico was born in Santa Barbara on January 1, 1935, the son of Ernest Pico and Georgia Guevara Cota Pico. He served in the Navy, was a friar in the Franciscan Order of the Province of Saint Barbara, and taught dance for many years. I had the pleasure of meeting him at his residence in Santa Barbara on September 13, 2018. Also present was a mutual friend, Anne Hollister, and Michael Giorgi, who arranged the interview. We chatted casually for a while, and then I launched into a few of my standard questions.

“What is your source of strength?” I asked him.

“God,” he answered, simply and without hesitation.

“And what are you most proud of?” I asked.

“All of it,” he replied. “My life. All the things I’ve experienced.”

But the theme that seemed to run through his reminiscences most consistently was dance.

In the following audio-clip, you can hear Ernie talking about some of his experiences as a dancer and a teacher of dance.

And here’s a telling little vignette…when you need to dance, you dance! (And is it madness, or joyful defiance?)

Ernie grew up in an area of Santa Barbara called Sycamore Canyon. “There were Indian caves we used to play in, as children,” he told us. “My dad said that when he was a child, there were paintings in the caves, but someone scraped them off. I never got to see them.”

“But Sycamore Canyon is very unique,” adds Anne. “It has high walls, but it doesn’t feel enclosed. There’s an openness about it, and when Ernie took me back into that area, I felt that the vibes were really strong, positive people-vibes. It felt like they all respected the land and used it appropriately for a long time.”

“It’s kind of hidden,” says Ernie. “You can’t see it from the street because it’s set way back, and if you don’t know how to get there, you’d miss it. My great-grandfather’s house is still standing. That was the Flores side of the family."

“I had three sisters. My mother taught us to clean house wash dishes, cook, and bake. We picked plums, apricots, and peaches, and gathered what we found growing nearby. I used to make salads with mustard greens and wild spinach. We picked blackberries that grew near the creeks and made blackberry ice cream and pie. I still love to cook.”

“I played with my cousins as a kid. We did challenging stuff. We walked on stilts in the hills to see who could walk up or down the hill without falling. We had contests. We had go-carts. We’d go up or down the road. There was hardly any traffic, and we’d pick up momentum as we’d come down, but there weren’t any cars to worry about then.”

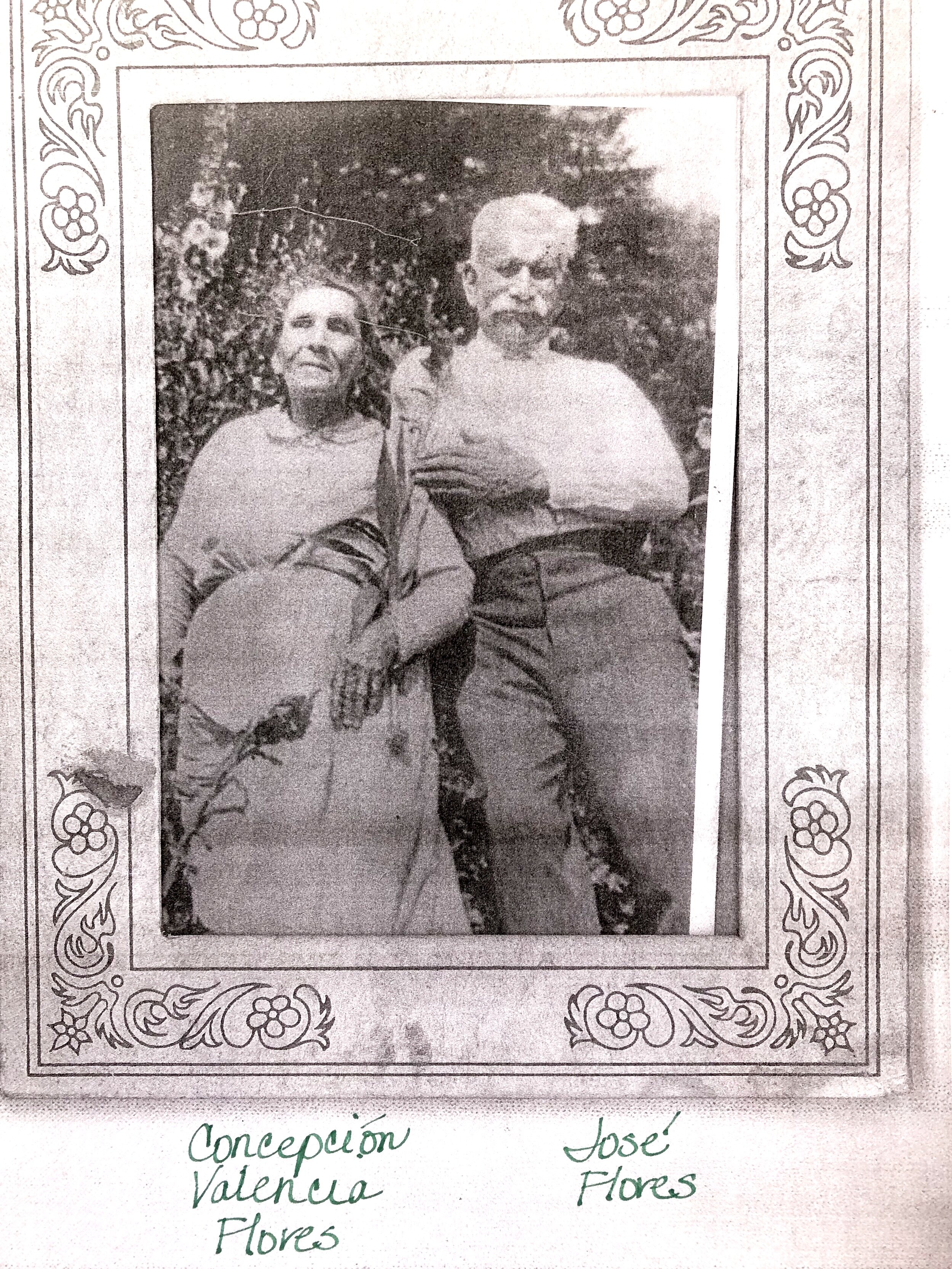

“My great-grandmother Concepcion Valencia, my father’s grandmother, was a full-blooded Chumash, born on the reservation in Santa Ynez. She died before I was born, but she loved to dance. Maybe that’s where the dancing comes from.”

In 1958, Ernie was part of a U.S. Naval unit stationed on Bikini Island in the Pacific during atomic bomb tests. “We were guinea pigs,” he told us matter-of-factly. “It was frightening. You couldn’t watch, or you’d go blind. We couldn’t even start the engines of the ship because the water was so contaminated afterwards, it would contaminate the ship. We had to sit, still as ducks, until the currents took it away. I later learned that a lot of Native Americans survived, and the rest had cancer.”

In the 1970s, while working for General Motors, Ernie started a program called Can-A-Month, to deliver and distribute canned goods to people who could not afford groceries. The “city fathers” were skeptical of it and sought to impose restrictions and regulations. They could not believe that anyone would run a program purely for the good of others without benefitting financially. “Anyone who says it is impossible to do something solely for others without personal gain reveals more about his own lack of character than anything else,” says Ernie. The program was eventually discontinued, but he is still proud of it.

In 1979, Ernie became a Franciscan Brother with the Franciscans of the Province of Saint Barbara, in Oakland, California. As a novice, he worked for a while with terminally ill patients and their families. In time, though, he found his way back to dance again, and through dance, he has made a difference in many lives. Even today, he is teaching seniors two days a week at Garden Court, a local residence, to “tone their muscles from their feet to their head”. It’s a prerequisite, he explains, for them to take a dance class with him.

He’s also skipping dinner once a week to take dance classes himself, because he wants to dance at the next Fiesta, and he intends to be in shape for it. “If I make it,” he says, “I’ll be the oldest performer on stage.”

Among my favorite stories that Ernie shared is this one, about teaching dance to the children at the Pala Indian Reservation, and taking them to see the ocean for the first time in their lives.

I asked Ernie what wisdom he would offer to a young person in need of advice. “You need to pursue what you want to pursue,” he told us. “If you’re not hurting anyone, go ahead.”

“How do you keep from getting discouraged?”

“Friendships,” he replied.

“And what is your current state of mind?” I asked.

“Lousy,” he admitted, with a laugh. “I have a lot of health problems. I have to have eye surgery. I’ve had a hip replacement, a pacemaker…I’m bionic. Now they want to do surgery for a pinched nerve. And I have leukemia. I’ll start next week at the cancer clinic. But I don’t dwell on the negatives. I try to stay busy.”

“And he keeps me laughing,” Anne was quick to point out. “He’s a very inspiring man, no matter what his health issues are.”

I can see that it’s true. Ernie Pico has a certain spirit and charisma, and I could not help but notice as we sat in the building’s spacious entry room, that everyone who passed through seemed to know him.

A sense of humor, a kind heart, and the ability to dance are pretty powerful attributes.

“How would you like to be remembered?” I asked him.

“As a dancer,” he replies.

A dancer it is. And a very good man.