“It’s a fun job, out by yourself. You spend a lot of time outdoors; you see a lot of wildlife. I get to ride different ranches and go into the hills with my horse. I see different views of places you’d never see from the road. And I get to do work I like doing.”

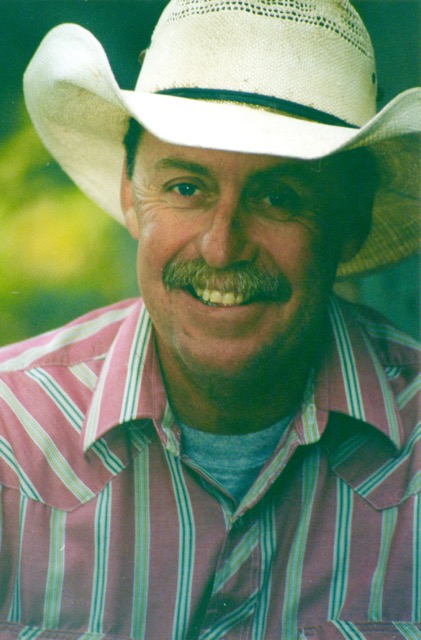

Jon Brough was born in Connecticut, moved to California at the age of five, and first set eyes on the Hollister Ranch when he was nineteen. He worked as an abalone diver in the Channel Islands for fifteen years, and his reminiscences reveal a lot about that now-vanished livelihood. When we talked to him, around 1998, he was earning a living day cowboy-ing at local ranches.

Jon passed away in January, 2014, two days before his 60th birthday.

“When I was diving, I got to see the Channel Islands and go surfing out there. I spent years out there; that was a real treat. I dove near San Miguel Island, which you can see on a real clear day, and San Nicolas, which is the furthest one out in the chain of seven islands. I used to hike down and could see where Indians used to live — back then you used to be able to just walk around — and there’d be kitchen middens — big piles of abalone shells — bowls, and lots of artifacts lying around at the camps.”

“The diving was not really hard work, although you’d spend seven or eight hours underwater — you don’t make a lot of money sitting out on the boat. Usually there would be a deck hand and two divers.”

“We’d use 600 feet of hydraulic hose and an air compressor on the boat, so we didn’t have a big tank on our backs, just a face mask and our wet suits and swim fins. Sometimes a deck hand might forget to turn the compressor on, or sometimes they would move the boat and the hose would wrap up in the propeller, so your air supply would be shut off, and then you’d just have to remember that you’re underwater, and it’s okay, and what you would do is come up slowly. If you come up too quickly, you get nitrogen bubbles in your blood, and they lodge — it’s called embolizing — and it could be real serious, so you always have to exhale, because when you’re down below, the air compresses. If you took a balloon down there, it would be this big, and then when you came to the surface, it would be much bigger, so you always have to remember that. If you held your breath when you were fifty feet down and swam to the surface, your lungs would blow up. So be exhaling when you return to the surface.”

“When the black abalone were healthy, there was a daily limit of twenty dozen, sold as a live product to Los Angeles and flown to Japan. With red abalone, we were allowed between two dozen and five dozen a day – the price started out at $90 a dozen, and went to $450 a dozen. They also went to Japan — the yen was more valuable than our dollar — it didn’t seem like a lot of money to them, but it gave us a lot of money.”

“The state of California closed abalone diving temporarily to study a disease which pretty much wiped out the black abalone. There are three different types that were commercially harvested: black abalone, pink abalone, and red abalone. There’s some white, like a pink. The abalone developed a disease or virus and they all started dying, so the state shut down the fishing for commercial and sport use in order to study the results of the disease. There’s no real cure for it, and it hasn’t really stabilized much, and they are not really sure where it came from, although they think it might have come from Korea when they were bringing oil platforms out on barges.”

“Before I became a diver, I was a sword fisherman. I’d go out on long trips, sometimes two weeks at a time. Abalone diving was just an overnight trip — you’d get to come home a lot more. The money was good, and when there was surf, you could go surfing, because the water would be too dirty to go diving. So when the surf was up, you couldn’t go to work — you had to surf — that’s my kind of job. It worked good that way.”

“When I was in high school I did a lot of ceramics and became an apprentice for a guy who was the head of the UCLA art department. He let me work in his studio and I went into business on my own. I made a lot of ceramics and sold them, but after awhile I didn’t like being indoors. I’m more of an outdoor person. That’s when I started commercially fishing.”

“I didn’t start horseback riding until about seven years ago. A friend of mine at the Ranch let me ride his horse, and I thought it was kind of fun, so I bought one. There weren’t many people on the Ranch who had horses then other than the cowboys, so I started riding with the cowboys, like John McCarty and Justin Cota and those guys. That’s when I started learning how to be a cowboy.”

“It’s all seasonal work. Right now the cows are calving, so there isn’t a lot of work to be done. In January, we’ll bring mother cows in with calves and start branding them. The brand is identification so they don’t get mixed in with neighbors, or for selling them. When we brand them we also vaccinate them and give them all the medicines they need so they don’t get sick.”

“The brandings are almost like a little rodeo, because we rope all the cows to brand them. One person will rope the head of the calf, and wrap the rope around the horn of the horse, and then you’ll rope the heels of the calf and stretch it out, and that way the calf can lie on the ground and you can give it its medicines and its brand and whatever it needs, then send it back to mama.”

“Next time, when they are bigger, you get them ready for shipment. You gather them again, give them vaccinations, separate them from the mother, then run them through scales, weigh them, and load them onto trucks. They get sent either to a feed lot or out to Nevada or Wyoming or someplace for the summer grass, because when we have grass out in California, they have snow, so we get some of their calves to graze out here. When our summertime comes, they have grass, so we ship our calves out there then.”

“It’s a fun job, out by yourself; you spend a lot of time outdoors; you see a lot of wildlife. I get to ride different ranches and go into the hills with my horse. I’ve worked at Cojo, a couple of ranches in Los Alamos, Lake Cachuma, San Fernando Rey, sometimes Simi Valley, and of course, Hollister. I see different views of places you never see from the road. And I get to do work that I like doing.”

“I enjoy our house and our canyon most of all — it’s my favorite place to come at the end of the day and get something to eat. But the whole Ranch is a beautiful place.”

“I’ve liked all my jobs. Everything is always work, and if you don’t enjoy your work, you’re not going to enjoy your life. There’s gonna be bad days and good days, but if you basically like what you’re doing, it makes it worth it.”

“As a boy, I liked to hike down cliffs and play in tide pools. I started surfing when I was eight years old and spent a lot of time at the beach. I liked to slide down the hills on cardboard through the mustard when it was dry and sticks. We made big tracks and slid down hills on them, mostly playing outdoors, getting in trouble outside.”

“My advice to kids is to remember there are all sorts of aspects of life. You don’t have to make any decisions for your entire life at age eighteen. Just stay in school, make it through high school at least, then decide what you want to pursue after that. Maybe you’ll want to further your education in college, but not everything is offered there. Find your passion.”

“Look how many times I’ve changed jobs. The main thing is to pursue what you like. There’s no reason why you can’t do what you want to do.”