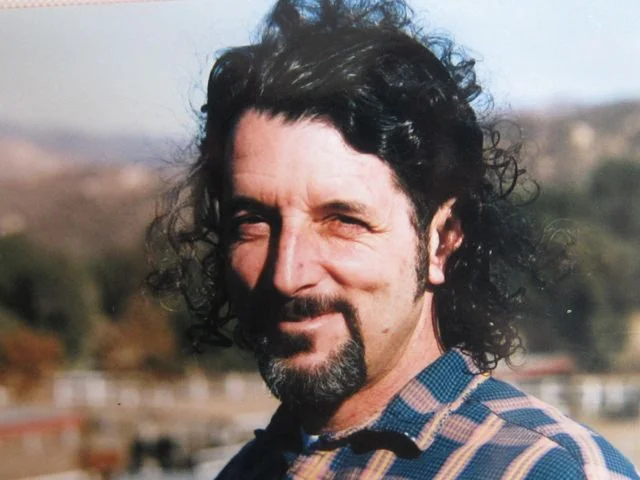

Richard Cunningham has been an inventor since childhood. His irrepressible spirit, love of life, and stunning creativity have led him through colorful adventures involving airplanes, motorcycles, bicycles, horses, journalism, bad guitar playing, and plenty of pain and ecstasy in the great outdoors. In 1981, he founded his own bicycle company, Mantis, whose bikes became well known for the "magic feel" of their ride, and in 1995 was inducted into the Mountain Bike Hall of Fame. Richard came to talk to the students of Dunn Middle School in 2002, when he was the editor of Mountain Bike Action magazine. In his spare time, he had been building an airplane, which was almost ready for its first flight. (He called it Lucky Dog, and there's a picture of it below, a handsome green and yellow plane adorned with four-leaf clovers.) The insights and stories Richard shared with Dunn's students are still fresh and fascinating, but he has gone on to many new chapters in the years since this this conversation took place. He currently draws upon his technical, historical, and riding expertise in his role as a journalist for Pinkbike.com.

Here he is, in his own words:

Airplanes are my first love. My mom told me she'd give me fifty bucks if I could build an airplane that would fly. I had no idea what it would take to build an airplane. Actually, I did have an idea, but it wasn't right. I made all sorts of contraptions with wings, and I covered the wings with old shower curtains, and I used skateboard wheels, which at the time were made out of steel. I took all this stuff to the largest hill in the city of Fullerton, where I lived, and then I would sit on it and go down the hill and bounce up and down, but I never took off.I was always picking through the trash on my way to school to find parts for an airplane. One day, I found this huge patio umbrella. It was made out of lightweight cloth, and it had a bamboo handle and steel ribs that came out from it, so I took it and stashed it behind the school. After school, I bent the front to make it look like an airplane wing, and I broke the handle off, so it was really little, and I could hold the handle with my legs, and the top of the umbrella was right above my head.

Fullerton is in the north of Orange County, right at the mouth of a canyon, and we had these incredible Santa Ana winds. You know when they build new homes how ugly they make everything with those huge embankments? Well, behind my school, we had one of those that was probably 200 yards long, and the wind blew right up against it, howling. I went up to the top of the hill, and I knew. I knew I could fly. I knew it would work. I would run as fast as I could and jump off the top of the hill when the wind was blowing. But I just crashed my brains out all the way down.

Then on my fifth try, I caught one just right. I was a little kid -- it picked me up, and I stayed about this high off the hill almost to the bottom. When I hit the bottom, I landed on the umbrella and cut myself to pieces, and the umbrella was shredded, but that was the first time I ever flew. I was so excited! I went home and told my parents, and my mother never did believe me. But I've loved airplanes all my life.

My dad worked in aerospace in secret projects back in the days everyone thought the Russians were going to drop a nuclear bomb on us. His life was entirely secret. He would go, he would come back, and he would work with slide rules (this was before computers) and draw things, but he could never talk about it, not until much later in my life, when I was in my thirties. That's when my dad built a little airplane, an ultra-light. You don't need a license if you make an airplane that flies slow enough, only takes one person, and weighs less than 250 pounds, so he built one. None of us knew how to fly. But we went out to this big dry lake, and we'd just sit in it. Sit in the airplane, hit the gas, and just try to fly level with the ground this high until you feel good about it, and then you take off and go.

So I learned how to fly just like the Wright Brothers. I didn't have flying lessons. Once you take off, once you pull back on the stick and it goes up in the air, it feels like the ground falls away. Anyone who's ever flown on an airline knows how that feels, except that the pilot on an airliner knows what he's doing.

Anyway, the dry lake is perfectly flat…as flat as the flattest freeway…six miles long and two miles wide. But at seventy miles an hour, you run out of six miles really fast. And I didn't know how to turn, and my runway, this giant runway, was behind me, which is bad luck in flying. So I just tried to remember what I'd read in the book - ten miles, it took me ten miles to turn around- and then, when I saw a beautiful lake below, I thought, "That's really cool!" and just when I got all relaxed and thought I was gonna land, I passed it again. Ten miles, 400 feet above the lake, and I couldn't tell where we were parked. All I saw below were motor homes with motorcycles next to them. They all looked beige from the top, and very tiny. But after awhile, I made this perfect landing, and that was it. I was thirty-five. It was the scariest and most beautiful moment of my life.

The bicycle is the closest you can get to an airplane. If you can ride a bike -- you know how you lean and turn? -- you can fly an airplane.

But the reason I got into bicycles is like most kids. It's the first thing you get that gives you the freedom to leave home and go just about anywhere in the city. When you get your first bike, and you realize that in fifteen minutes, you can be five miles away, that's a huge distance. I don't know if any of you guys ever went cruising around on your bicycles and just exploring, but when I was a kid, where I lived in Orange County, it was like here in the Santa Ynez Valley. Now it's covered with homes and the Disneyland Matterhorn is visible about fifteen miles away…but in those days, it was all orange groves, and little tiny paved streets, and dirt roads, and hills. I was pretty much a solitary kid, one of those boys you see all by himself playing in the dirt somewhere. That was me. So when I got my first bicycle and my parents would allow me to actually leave the street, it was freedom. I rode for miles. That's the reason I like bicycles so much. It's just you and the road.

Bicycles were the first non-powered things I fell in love with. My entire life, even as a child, I loved anything that had an engine and wheels on it. I built go-karts from old lawn mowers that were just pieces of wood with sticks and wheels nailed onto them and fan belts to get 'em along. I crashed my brains out in a million different ways. And back then, police didn't give you tickets for riding on the street, so I built race cars, and hop-up stuff for race cars - I had everything you can imagine.

One day I went back to that same hill where I used to take my airplane. I figured I could just roller skate down this entire hill. Everything seemed perfect. Of course I can do this! It just seemed so natural. Back then there were only two kinds of roller skates: the kind that had clay wheels that looked like plastic, and the kind that had steel wheels. I had the steel wheel kind. So I tightened them up and went way up to the top of the hill. All of my friends showed up - I thought they showed up to see this miracle high speed run I was gonna do, but really, they only showed up because they knew I was gonna eat dirt.

I had a red scarf that I'd made out of torn sheets, and I was so confident that I would just fly down this thing. I started off nice and easy, going pretty good, my feet were kinda moving a little bit, but I was still okay. Now I start going really fast, and now I'm beyond the point where I can fall, and I can't run. I'm really beyond anything. I knew I was in trouble. The skates were steel, and on the asphalt, they vibrated so hard, it hurt my feet. It was like somebody was pounding nails into the bottom of my feet.

It's getting worse and worse, and I'm going too fast. What am I gonna do? I'm not gonna make it to the bottom. I was gonna crash in a second. So I was gonna jump. I just leaned a little bit. But ever feel so afraid that you just lose all power in your body? It feels like somebody stole your ability to move, like in a bad dream. That's it. I hit the curb with my skates at an angle, bounced off the roots of a big tree, and just sailed into the parking lot of the Catholic school.

It took me months to heal. I stuck to the sheets for months. Every part of my body was dripping.

I had a lot of little crashes, but that's my first good one. Later, I broke my hip testing motorcycles. You had to test every kind of motorcycle that was ever made. I was racing through the roads around town, and I just fell. The motorcycle was sliding and skidding and it slid and pinned me between the curb and the motorcycle and it cracked my hip, and there's nothing you can do for a cracked hip but just heal. I was on a cane for almost two years.

I raced motorcycles for many years, up to the time I was about twenty-two, I was racing them on the dirt. I loved it. I used to go trail riding in a certain place in the desert. When I first went to this place, it was beautiful. There was a creek over here, bushes everywhere, and a little place to park your car. Well, I kept coming back as time passed, and thirteen years later, it was just a couple of bushes and all dirt. One day I realized that we had done that. We had ridden our motorcycles around the bushes to the point where those got destroyed, and everything just became dirt. And I thought, "You know? I've spent most of my life making race cars, building motorcycles, and making motorcycles faster. But there's got to be an end to this. I'm not doing something that's making the world better. It's making it more fun, but if you look at my space…I went here because it was beautiful, and now it's denuded."

This was an important realization for me, and it involved my livelihood. I had a shop, I worked for other people, this was my living. But I kinda started thinking about it then. And several months later, I was under an expensive race car welding little exhaust parts onto it, and a ball of metal that came off the weld fell down and landed on my private parts. Now when a hot ball of metal lands on skin, it bounces around and leaves thousands of little pock mark burn holes, and I couldn't just run away, I was under a car, and I had a welding torch in one hand, and I just had to wait it out. And that's when I knew that I didn't want to participate in this world anymore. There are enough people who make cars, enough people who think cars are the coolest things in the world. I wanted to do something that made a better world.

I kept my shop, but I closed it up, and I went rock climbing and mountain climbing for a couple of months and just did nothing, and when I came back, I got a job in a bike shop. I still loved bicycles. And that's how I started out. I worked for a dollar seventy-five an hour or something like that assembling cruisers with air wrenches in the back of a Schwinn shop. No one ever saw me. I was just a noise in the back.

So I went from being this guy that had his own business, to the lowest of the low at this cheesy bike shop in Fullerton, but I loved it. And some time later, I got a job at a place called Medici Bicycles, and they made custom road racing bikes. I started riding road bikes and ten speeds, and I even wore the little fruit outfit - like is that a real man, or is that a fruit advertisement? I loved it, but eventually, I ran out of places to ride on the road, for a hundred miles in every direction. 'Cause once you're fit - I was riding 200 or 300 miles a week during the hot season - once you're that fit, you've ridden everywhere there's pavement for a hundred miles in every direction.

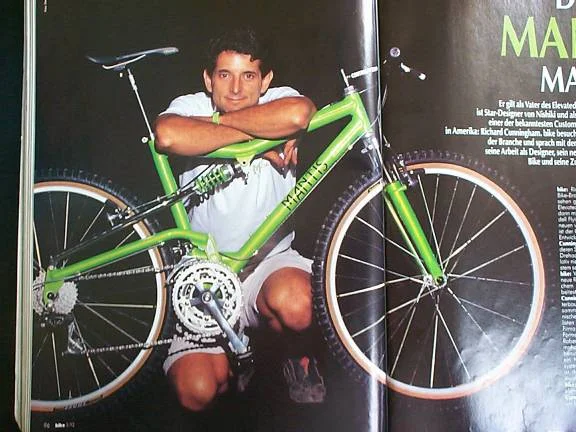

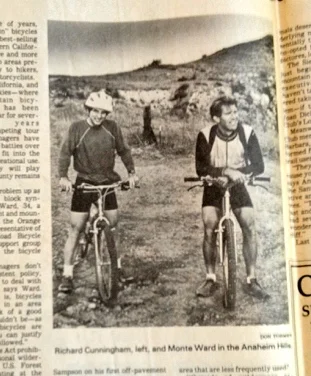

Now I started connecting the dirt roads with a road bike. I'd go over the mountains on these skinny dirt roads and I found out I liked that even more. But the whole time I was going down these sandy fire roads on these tiny little road bikes in my fruit outfit, passing four wheel drivers and motorcycles, I was thinking wouldn't it be cool if I had big tires and motorcycle handlesbars and all the other stuff? And then years later, I heard of this guy named Monte Ward who had gotten one of the first mountain bikes from Northern California. He was riding on all the dirt roads. So I thought, "I'm gonna build me one of those things." When the right rims and the right tires came out, I was already working at a bike company. I just went back to my shop, and I made my first mountain bike, the first Mantis. It was 1981. From then on, I never rode the road again.

That bike looked great, but it needed to be taken for a real ride. Monte was going out to do what at the time was considered one of the hardest climbs in Orange County, and this was a good opportunity to ride along with him on the beautiful red Mantis, but I was totally out of shape, so I wanted someone else to ride. I didn't believe I could stay with the mythic Monte, best climber in Orange County, the man everyone deferred to when it came to mountain biking. I had heard so much about this guy. When I met him, I was completely intimidated. I think we had three words, and then my friend rode up there with him and came down and said that my bike handled the worst of any bicycle he'd ever ridden in his life.

Eventually, I started riding with Monte, and he basically took me on my first awesome mountain bike ride. We climbed a lot, we carried a lot, and got back at night, so I think I learned that through Monte.. We eventually became friends, and that will probably last for the rest of our lives.

I don't own that first bike anymore. I was so poor, that I sold almost everything I had for the first ten years. Everything I could sell. I sold a '56 Ford pick-up truck, which now would probably be worth a hundred thousand bucks because they're the vintage, "must have" truck. I sold it for $300 because I had to pay rent. So then I didn't have a car, and I rode my bicycle, and then I needed to pay rent again, so I sold my mountain bike to pay rent for that day. When you're in business, and you're barely making it, you have to have money, so whatever it takes. Basically, if you were my children, and you weren't working at the bike shop, I would consider selling you just to pay the rent.

But it was an exciting time. Have any of you been part of a new sport, something that just starts out? Like snowboarding, or something like that? Here's the deal. When a sport first starts out, it's so new, just doing it is really fun. When I first started making mountain bikes, there were no boundaries. A mountain bike could be anything you could ride on the dirt. Nobody knew what made a good mountain bike, or what made a bad one. So I had a chance to experiment with different tubing, different types of arrangements that made a bike go faster or climb better, and it made a big difference each time I discovered something new. It made a huge difference in what you were able to do. If you bought one of my bicycles in comparison to the other ones, you might find that this thing climbs better than some other cheesy brand, or maybe it goes downhill ten times worse than Tom's bike. But each bicycle has its own personality, and it's in the technology.

That's what I was participating in. It wasn't just bicycles. I was participating with a very small group of other men and women who were making bicycles all over this country. We were creating a new sport. It was like we discovered gold in California and nobody else knew about it. So the fun was in the making of the bicycles and the building of the sport.

We went to all the biggest bike shops from Santa Barbara to San Diego trying to sell our bikes. And you know what they told us? We can't sell a $1200 beach cruiser. And they threw us out. We didn't sell one bike. And these are the bike shops that are now considered the mountain bike centers of their communities. That's how new it was back then. So we put on slide shows just to sell bicycles. There were slides of us riding downhill, and standing next to sunsets and stuff. They would look really goofy now, but we actually did slide shows to tell people about mountain bikes.

But the reason I stopped making mountain bikes was because at that time the small builder- designer-engineer guys began to have less of a role to play. Here I was making maybe 500 frames a year, and companies like Specialized and Nishiki are making 20,000 and 30,000 bikes at a time. So there wasn't as much need for a small manufacturer like me as there was for a large manufacturer to produce big numbers for less money. My bicycles cost at the time $2500 each and you could buy a fully equipped bicycle with the same amount of parts for about $700 or $800. So I looked at it and I went, "You know? It's time to do something else."

The editor job came up when I still had a bike company. My friend Zapata Espinoza quit his magazine job and moved to another magazine. My wife said, "You've been looking for something to do. You should try for that job." This is really funny, too. I didn't know how to type. I got Fs and Ds most of the time in school. I don't know how to spell. I didn't know how to use the computer. All the skills an editor needs to know. But I did know a lot about mountain bikes. So I called up the magazine and said, "You know, Zap's leaving. Why don't you put me on the list?"

And the next day I got the job. Now I had a company to sell, and I had all that stuff to learn, like how to write stories without knowing how to type. In one year, I had to learn everything about magazines, how to use the computer, and all the stuff that went with an entirely new job. I think it was the biggest change I've made in my life in any one day…other than being born.

I've been there for eight years now. It's the greatest job on earth. I get to ride bicycles and travel all over the world to do that, to ride bicycles in the national parks in Switzerland, or somewhere in Brazil. I can go anywhere I want, pretty much, wherever they ride bicycles, and then I can just go home and write stories about it, and I get paid to do that. It's a great job.

It's easy to write about bicycles. You see a bike, you ride it, and then you talk about it, or type about it, like you were telling your best friend. That's the easiest way to write a story, like you're writing to your best friend. But in my own column, the first page of the magazine, you're supposed to be brilliant in just one page. And sometimes, I just don't have anything to say, so I break it up. For two times, I talk about something that's important, or something technical, something I like or something I hate -- that's kind of political-- and the third time, I just tell a cool story. The last story I wrote was about me when I was about four and a half feet tall, digging through the trash and getting in trouble in Catholic school, and having the nuns yell at me.

It's challenging to try to write a one-page story because you have to take out a lot of stuff that you think is important. It's easy to go on and on like I'm doing right now, boring you to death, but if I had to say everything in one paragraph, I'd really have to think it through. So that's it. A one-column story is a lot harder than anything else to write.

Mountain bikes are just about enjoying yourself. A new generation has discovered mountain bikes now and just uses them for localized stunts and fun stuff. It's like the skateboard crowd where you just hang around a certain area and do like drop-in and all that stuff. They do the same thing but on more natural terrain, and that's the cool thing now.

Free ride is the hottest thing in bikes today. It's a heavy-duty mountain bike with long travel suspension, primarily used for downhill, but you can still pedal it when you have to. It's popular for same reason as snowboarding. You can do all sorts of tricks, ride difficult terrain, and even though you can't use it for extended cross-country, it allows someone to just go out and play.

Where are bikes headed? Forty or fifty years ago, there were the old Schwinn cruisers, no gears. We're kinda going where it was back then. At one time the mountain bike was the coolest thing in the world, not because you could ride on the dirt. It was because when you went to a bike shop and asked for an expensive light weight bike, they used to give you a 10-speed with stupid handlebars and a little skinny seat that was more like a butt wedge, but that was the only place you could sit. And the tires were so skinny that the first time you dinged 'em they would go flat. So what happened was you had a bicycle that was uncomfortable to ride, everybody hated it, and it was stashed in the garage because it had flat tires.

When mountain bikes came out, they had upright bars, comfortable seats, and the tires were big so if they had a leak it would still hold air for awhile. So suddenly, everybody had the bicycle they were begging the bike shops for, even though they never rode them in the dirt. Now mountain bikes have been around for a long time, and they really are bicycles for the dirt, not just ten-speeds with fat tires. So when you go to a bike shop, they don't say, "You need a mountain bike." They say, "What are you gonna do with it?" So you say, "I'm just gonna ride on the board walk and pick up chicks." So they say, "You don't want a mountain bike, you want one of these comfort bikes. They look kind of butch, but they've got skinnier tires, the seat's comfortable, and the handle bar's even higher."

Mountain bikes spurred everyone to go out and reinvent cycling. And rediscover it. But now that everyone's riding again, they don't necessarily want a mountain bike, and mountain bike sales have gone to one third what they were. (And so have the sales of my magazine, by the way.) Everyone realized they don't want to go out in the dirt; they just want a cool, comfortable bike. The market realized that, too. It's specialized. You can buy a bike for any purpose.

As you get older, you have a higher tolerance for pain, so you can do longer and longer rides because you know you're not gonna die. The hardest thing I ever did lately was a twelve-hour ride in the Los Padres forest. The trail I was looking for was mismarked on the map. I missed the junction I was supposed to take, and I ended up climbing through the bushes for four hours. It was dark when I got back onto the ridge. On the way back, the short way was to the right and the long way to the left. I met a Jordanian man with his child on the dirt road, and I said I was going to the right, and he said, "No, you do not want to go that way. It is very steep." But I said, "I know, but I just climbed up an entire mountain carrying my bike." He says, "No. That may be a road on the map but it is very steep." I was with a friend. I said, "We're gonna do it anyway." He said, "Is okay with me, but now you will know the meaning of steep."

So I walked up the steepest road I have ever been on in my life. There were motorcycle tracks that went off the road and into the forest because it was too steep for motorcycles. I was so tired. And when we got back to the car, my friend had forgotten the keys to the car! We'd started twenty miles away; we were supposed to end up at this other vehicle. No keys. We had to call a locksmith and have them make the keys to get into the car. We were starved, we were cold, we were in our shorts, and it was the middle of the night,

I only have three friends who will go out on rides with me anymore. The rest of them say no. They call it a "Richard ride." It isn't a Richard ride unless it's dark when you get back, and you are lacerated by bushes. There has to be a considerable amount of pushing, and you have to get lost at least once. I used to think that was a joke, but when I look back on all of my favorite rides…they are like that.

That's the whole thing about being outside. No stores. When something goes wrong, if you don't have it in your bag, you walk or you spend the night. But you really explore. You see a lot of stuff that you'd never in your life see, even when you're miserable. It's cool.

One time we were carrying our bikes for twelve miles into a canyon near a creek, one of the most spectacular places I've ever been in my life - at every bend, a swimming pool with waterfalls, piles of turtles on every rock, and a bear ahead of us the whole time. His footprints were filling up with water when we went through the crossings. The water was so deep, we had to carry our bikes over our heads, or we had to swim across. It took us twelve hours to get through the canyon, but that was one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen in Southern California. There were Indian caves with all their stuff still there, the rocks they had used to grind acorns, totem rocks, everything still arranged like they had just left yesterday. It was unbelievable.

There's no such thing as modern times. Less than a hundred years ago, the last of the Chumash Indians were driven from their ancestral villages. They were stone age people. They didn't have clay pottery - they wove their baskets and carved everything out of rock and they had flint tools all the way into the era of steam engines, and when the Wright Brothers were flying their first airplane. And when they grew up, they wanted the same things we want: they didn't want to die without making a difference in the world, they wanted to be loved, they wanted to have babies, and do the stuff we do, just in a different form. They had the same questions. So there's no such thing as modern times.

Photo by Dean Bradley

My advice…and I'm still struggling with it a little bit…is that there's a lot of stuff you're expected to do but you should really concentrate on what you want to do, what really makes you the most excited about life. And if that means getting fat and having babies and raising kids, or if it's putting roofs on houses, that's fine - because there's honor in doing what you want to do and doing it well.

I really wanted to make bikes and get a job in the bike industry and make a difference by doing this, and the whole time I was at Mantis, for the first ten years, I never made more than ten thousand dollars a year. I was poor the whole time. And my dad and my friends said give it up. You've tried hard; you've done a good job; just give it up. But I really wanted to do it. And somehow, because I just kept working at it, I found an angle that worked, and it was really fulfilling.

So never downplay something you really believe in, something that really makes you happy, because that's where you're the most creative. When you're doing something you really enjoy, you get that spark of creativity, and that's what drives the human soul. Make a difference, and feel good about it. Don't lose that one thing, even if it's contrary to everything that everyone else says -- keep it alive, and you'll find that it will take you to the next step.

And the other thing is I'm not telling you to only do things that come easy, because I would have never gotten the job at the magazine if another thing hadn't happened shortly before, and that is a guy named Jay who had a bike shop walked into my shop at Mantis and gave me a Fender telecaster electric guitar. Now I can do a lot of things really well, but I suck at the guitar. I have no rhythm, I sing like a crow, and my fingers don't fit on a guitar. Suddenly here's this instrument, and it was beautiful. It was the most gorgeous guitar I've ever seen, and I've been around music a lot, and I sat down and started to play it, and I was horrible. I had to buy the lowest level books, and I had to go through them and work really, really hard just to play bad, and it was humiliating. It was humiliating to be so bad, because some of the guys at Mantis, like Eddie, the tall guy, were musicians, in a band, and it came easy for them. It was humiliating to learn something from the ground up at thirty-nine years old that everyone around me knew really well, and then to have to work hard just to be bad at it. These guys were singin' and jammin' really well while I was just figuring out the chords.

So then, when it came time for the magazine job, the editor job, which was really a cool deal, I didn't know anything about computers, and I didn't know how to type, I didn't know anything about the magazine, but I'd just learned how to play the guitar. And I realized that day that it wouldn't be any different. I'd just go in and start with the basics, and learn it, just like I'd learned the guitar, and it led to this.

So I'm not telling you to do things that come easy for you. I'm just telling you to follow your dreams and do whatever it takes to be able to do what you want to do, even if it means humiliating yourself and learning something you're bad at. And I still love guitars. I play every day, and I still suck.